For Noyes Foundation, Fixing Food Means Racial and Economic Justice

/The problems in the modern food system run very deep, says Kolu Zigbi. At the root, there's a history of racial injustice—from appropriation of native land to reliance on slavery—that lingers in modern policy.

“That legacy of the inequities of our agricultural past are still being fought today,” says Zigbi, program director for Jessie Smith Noyes Foundation’s sustainable agriculture and food systems grantmaking. But as communities seek to move away from industrialized agriculture, there's opportunity.

“It also opens a way for us to build structural equity, because there are people of color and low-income people throughout the United States that are organizing and understand that there’s promise in the food system," she says.

Zigbi and the foundation she works for have no small aspirations when it comes to food and agriculture, seeking to shift power in the production and distribution of food, and to bring those who have been historically marginalized within that economy back to the table.

“Our theory of change is that bringing about a sustainable society—and the food system is part of that—is a really grand endeavor, and that when we look back at how social change happens, what we see is that social movements have been key drivers.”

Noyes is a national, New York-based funder established in 1947 by Charles F. Noyes, a Manhattan real estate tycoon. Its current funding priorities are environmental justice, sustainable agriculture and food systems, reproductive rights, and an environmentally sustainable New York City, with grantmaking linked by an emphasis on equity and building grassroots social movements.

The core of its food and agriculture work is finding leaders in the most affected communities—often lower-income people and people of color—supporting their work, and amplifying their role in the national food movement.

Using philanthropy to bring about systemic change is a challenge not all foundations are up for, and it’s certainly tough in the food and agriculture realm. It’s a big jump, after all, to get from a farmer's market or urban garden to a healthy and sustainable nation.

Related:

- The Bumper Crop of Funders Working for Sustainable Food

- An Interesting Twist in the Growing Feast of Food Philanthropy: Creative Placemaking

It’s been an increasingly hot area of philanthropy over the past decade or so, and part of the reason funders like Noyes are so drawn to the food system is that the stakes are so high, with cascading ramifications in public health, poverty, ecosystems and climate change.

“[Agriculture is] sort of the most basic element of an economy,” Zigbi says. It's where our economic actions directly link us to nature. “Getting it right in the food system is a very core piece of having a right relationship with our planet and, culturally, with each other.”

Zigbi’s exposure to that cultural importance of food and agriculture goes all the way back to her family heritage. Daughter of two immigrants, her father is from Liberia, and as a teenager and young adult, she visited her family’s small village, which subsisted on rice farming and very little trade.

“I was so fascinated by the idea of people having the capacity to provide everything they need,” she says.

But Zigbi also came to understand that even the most self-sustaining communities need a level of outside trade and support, and that can all too easily turn into exploitation or neglect. This led her to study development policy and international aid, and the necessity of coupling community organizing with advocacy to make a difference.

She had a self-designed major at Stanford in rural development studies with a focus on West Africa, but ultimately followed a career path in her home in the United States, New York City.

Zigbi started out as a group counselor at a drug rehabilitation center in the late 1980s, then worked as a housing advocate, before finding her way to grantmaking on the Community Funding Board of the North Star Fund. She’s been at Noyes since 2000.

Since she joined, the food program has developed an interesting approach to a complex and multi-tiered problem, while working with a relatively small annual portfolio of $350,000.

The idea in a nutshell is that social movements create change, and the most effective social movements are diverse and led by those most affected by the problem at hand.

“Who has skin in the game to bring about social change?” Zigbi says. “A lot of people can sort of sign on, but the real leaders and the folks who are really committed to the long term are the people who are most directly affected.”

Noyes is also a national funder, but in backing state and federal food advocates in the early 2000s, found it had basically maxed out at 19 percent of grantees led by people of color. There simply wasn’t enough diversity in the higher levels of the movement.

“To diversify our portfolio, but also to diversify the movement, we would have to fund at a local level.”

They also had to be strategic about it. They couldn’t give everywhere, after all, and still wanted to make a national impact.

So in 2005, Zigbi and the board settled on its current approach—the food and agriculture program only funds at the local level if the organization is led by people of color, and only if they are actively bringing their leadership to the broader food movement through state, regional or national networks. All of the national groups the program funds have memberships made up of state or local-level members, and their boards are primarily or entirely made up of representatives of those member groups.

This allows Noyes to selectively back action by a more diverse set of activists, with the idea that their influence will then work its way up into the broader landscape. The foundation’s approach has translated into some impressive programs.

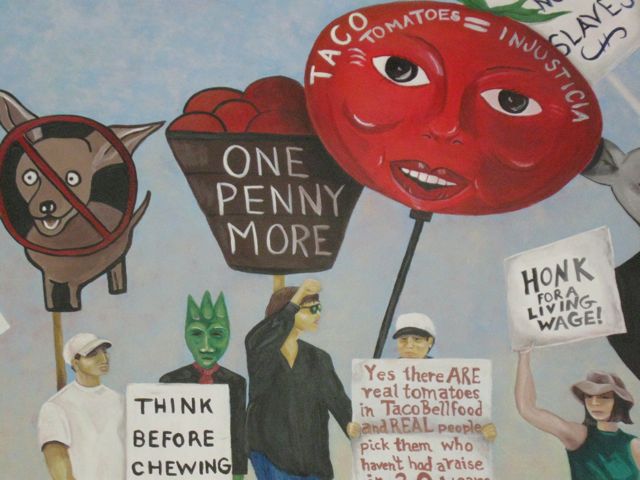

For example, Noyes has made multiple grants to the Fair Food Standards Council, which grew from a successful campaign by the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to improve conditions and wages for tomato farm workers in Florida. The campaign organized retail food giants to put pressure on growers, and has since expanded into other states.

In another example, a group of Hmong immigrant farmers in Massachusetts sought USDA funding to install high tunnels (a type of greenhouse) that would extend their growing season. But the federal grant policy at the time didn’t include the structures, so the farmers worked with Noyes grantee the Rural Coalition to organize for a policy change. It worked, and the USDA ultimately launched a pilot project, funding the Hmong farmers to test their benefits. Today, USDA funding for high tunnels is available in all 50 states.

That’s sort of a textbook example of how a marginalized community can trigger widespread benefits. A great outcome, but Zigbi says the true goal of the foundation is less about the projects and more about the capacity for grantees to organize and build power. While there’s a lot of funding for local food systems projects, funding for organizing capacity is lacking.

“We trust that, if you build people’s leadership, they will create the necessary programs. We don’t see the program as necessarily the end product,” Zigbi says. “The outcome that we’re invested in is the ongoing ability to affect change. I don’t think there’s enough of that.”

In addition to grantmaking, Noyes is part of a growing trend of funders using investments to make an impact. Zigbi likens investment to flowing water, and low-income people and people of color are often stuck uphill. “The more money you have, the more money you can get.”

Foundations can make investments to redirect that flow and create a channel for further investment. That way, marginalized communities can gain an economic stake in a future food system, while advocates strive to make a system that's more sustainable and healthy, in which power is less concentrated.

“My belief is that [a more sustainable food system] could happen, but we do still have to pay attention to racial equity and racial justice,” she says. In other words, we still have to confront the underlying issues.

“Otherwise, the ownership may be more diverse and more locally owned, but it won’t necessarily include people of color who have been left out of the mainstream.”

Related: