Three Key Things to Know About That Giant Neuroscience Gift

/

An active philanthropic couple made one of the largest gifts in recent years toward neuroscience research, a field increasingly known for drawing massive contributions. Here are a few important takeaways.

Joan and Sanford Weill, the latter being former CEO of Citigroup, just made a $185 million commitment to the University of California-San Francisco to establish the new Weill Institute for Neurosciences. It’s the largest gift UCSF has ever received, and while not the largest the couple has made in a long run of donations to various educational, medical, and arts causes, it does tip their philanthropy past the $1 billion mark.

A while back, we named Sandy Weill one of the most generous leaders of the financial sector, noting that he and Joan were parting with big chunks of their wealth through aggressive "giving while living." This latest gift further underscores that fact, and it brings the Weill's impressive philanthropy back into proper focus after last year's debacle of a cancelled naming gift to Paul Smith College.

Related:

- The 18 MostGenerous Philanthropists in Finance

- IP Profile of Sandy Weill

- No Glory, No Gift? Lessons From PaulSmith’s College Aborted Name Change Fiasco

In some ways, this big neuroscience gift is your run-of-the-mill gigantic research institution grant, but there are some interesting dynamics at play. Let's take a look.

It’s just the latest in a scorching hot field

It says something about a field's philanthropic popularity when $185 million can get lost in a salvo of comparable donations, as is the case with funding for neuroscience and neurological disorders. Within the past 10 years or so, we’ve seen some huge influxes of cash from private sources toward the field.

Paul Allen has made brain science his signature issue (although his interests are ever-diversifying) with total giving hitting $500 million, plus additional funds for Alzheimer's research. Big science funders like the Kavli Institute and Simons Foundation have stepped up funding efforts for brain research. And if you widen the scope to research on mental disorders in general, you’re looking at billions given just in recent years, including Ted Stanley’s $650 million commitment to psychiatric illness.

Related:

- A $650M Fist in the Eye of Cuts to Mental Health Funding

- Is Philanthropy Helping to Usher in an Age of Enlightenment for Psychiatric Research?

- This Science Funder Is Doubling Down on Brain Research

- Inside Paul Allen’s Quest to Understand the Brain

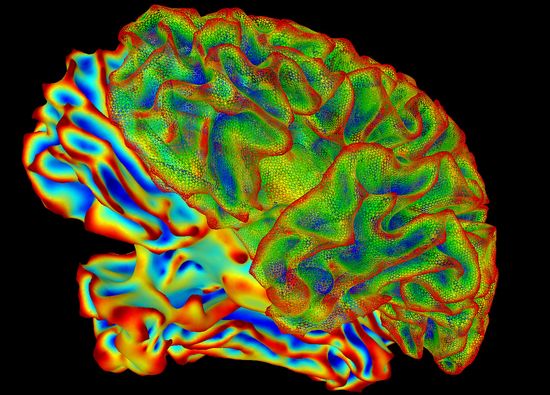

This is due to a combination of factors. For one, the field is booming right now, with brain scanning, microscopy, data analysis, imaging, and genomics advances yielding deeper understanding of the brain. There’s also federal momentum like President Obama’s BRAIN Initiative, although on the flipside, NIH cuts have prompted private investments as Band-Aids. Many people are passionate about the topic, some of whom happen to be billionaires.

Once again, the gift is highly personal

It’s not always the case, but very often, we see these mammoth gifts motivated by personal experience. It seems to be especially the case when it comes to brain science. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke estimates neurological disorders like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and autism spectrum disorders strike 50 million Americans a year.

Watching someone experience any serious disease is painful, but when someone you care about suffers from some of these neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, it can be particularly personal and brutal. While some criticize philanthropy steered by emotion, it plays an undeniable role in delivering surges of much-needed funding.

Paul Allen’s mother suffered from Alzheimzer’s, Ted and Vada Stanley’s son has bipolar disorder. And Sandy Weills's mother also had Alzheimer’s. Additionally, his father had severe depression, and one of his best friends committed suicide. Sandy Weill is now 83, and the couple have seen friends battle Parkinson’s and ALS. That particular combination of life experiences also uniquely influenced this gift.

It’s about breaking down boundaries

Another common thread we see in big university research grants is efforts to unite separate disciplines. It’s been a hallmark of grants to areas like biomedical research and data science, for example, with donors collaborating with university leadership to create a setting for creative collaboration. The research topics and neurological issues mentioned above are related, but they don’t always live under the same roof when it comes to how they are studied.

Related:There's Moore Where That Came From: A Donor's Vast Giving to a Top Science School

In the case of the UCSF grant, the couple was interested in bridging psychiatry and neuroscience—the former being rooted in study and treatment of disorders, the latter traditionally basic research of nervous system biology. The Weills particularly wanted to bring psychiatry and neuroscience under one roof, in hopes of removing the stigma associated with mental disorders and recasting them as diseases of the brain.

But there are tangible research benefits. For one, the center aims to unify research and patient care, by supporting both labs and patient clinics. Also, the more we learn about the brain, the blurrier the lines between fields get, and the more hope there is for turning neuroscience advances into patient treatment—something that has been slow to develop. Those involved in the future center hope to see more interaction between different the arenas.