Atlantic's $200 Million New Thing Is Big and Bold. But Will It Actually Work?

/

We told you there were going to be “fireworks” as Atlantic Philanthropies wrapped up its grantmaking this year, concluding an epic $8 billion giveaway of Chuck Feeney’s duty-free fortune.

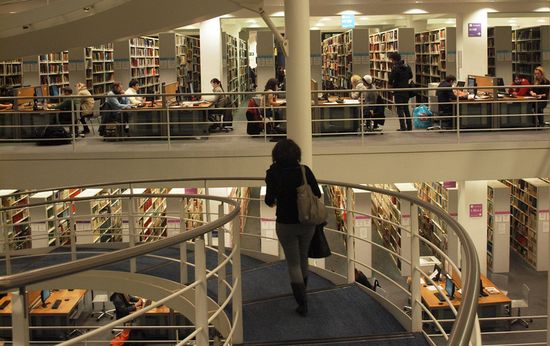

The latest move, which definitely feels like a finale, came yesterday as Atlantic announced $200 million in investments to create a community of leaders that can promote equity on a global scale. Nearly half of that money will establish a new Atlantic Fellows program at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). The larger half, $106 million, is a 15-year grant to create the Atlantic Institute, which the foundation says will be a “nexus” for the fellows to collaborate as they work to make the world a better place.

“Change is always about people,” Chris Oechsli, Atlantic’s CEO told me. And the idea, here, is to create a “community of actors” that will have a big impact on equity challenges worldwide.

I’m glad I had a chance to talk to Oechsli, because he made a strong case for an initiative that otherwise feels a bit dubious.

There are a few reasons why something like this could be a bust, starting with a flaw of many fellowship programs: They don’t create much change. Rather, people enjoy a swell gig for a year or two, and then resume their normal lives—without getting stitched into something with continuing impact. Fellowship programs based at big universities can be especially weak, since it’s easy for outsiders to feel disconnected in such places. Atlantic Fellows will be housed at LSE’s Inequalities Institute, but if you’re familiar with campus institutes, you know that they can feel like ghost towns, as busy academics float in and out, hyper-focused on their own research, while visiting fellows wait around for the next seminar that’s supposed to create community.

Then there’s the fact that Atlantic fellows are slated to be such a diverse lot. The foundation says they will be “researchers, teachers, health professionals, activists, scholars, entrepreneurs, artists, writers, government officials,” and others working on a range of issues in different places. Getting such a grab bag of folks to meaningfully interact and learn from each other during finite fellowships sounds challenging. It can be hard enough, as we all know, to get people who work together for years in the same organization to engage across silos.

These are all the reasons I was inclined to think that Atlantic might well be wasting $200 million, when I first saw the press release for this new program.

But Chris Oechsli and Atlantic’s staff, it turned out, had already thought of all the ways that fellowships can fail and built an initiative designed to avoid the obvious pitfalls.

Atlantic's strategy has included supporting emerging leaders for the past few years. And in that time, the foundation has studied hundreds of fellowship programs and other efforts to build human capital and leadership. Oechsli described a “listening tour” to me, during which he talked to people around the world who had been involved in various fellowship programs.

One flaw the foundation quickly identified is that many programs don’t have a mechanism for ensuring that fellows really collaborate—not just when they’re fellows, but for years to come, with ongoing support to ensure that they sustain their ties and continue to learn from each other. Atlantic’s answer to this problem is the Atlantic Institute, which will have the resources to foster collaboration and support a growing network of Atlantic fellow alumni.

(By the way, slapping its name all over this thing is unusual for Atlantic, but Oechsli told me he thought there could be real benefits from the cachet that comes with being an Atlantic Fellow. He’s got a point, if you think of, say, how MacArthur’s brand relating to its fellows rings a certain bell.)

The Atlantic Institute will be based in Oxford and—speaking of brands—run by the Rhodes Trust, which knows a thing or two about fostering ongoing community among leaders after over a century in this business, during which it’s created a famously powerful network of alumni.

Oechsli told me that hooking up with the Rhodes Trust was a key step forward as Atlantic tried to formulate its own plans. Among other things, the trust has been focusing new energy on working with people who are already “doing something out in the world,” as Oechsli said—these are the kinds of people Atlantic wants to boost as leaders. There were a “lot of parallels with what the Rhodes Trust was trying to do and what we wanted to do,” he said.

Meanwhile, LSE is hardly your typical university. It has a long history as a hotbed of critical—and often, radical—thinking about inequality, and its new Inequalities Institute aims to elevate that tradition. Here, too, Oechsli and Atlantic came along at a fortuitous moment, just as the institute was taking shape. The Atlantic Fellows will be baked into the operations of this place, rather than a tacked-on program. The plan is to bring in 600 fellows over the next 20 years, with recruitment now getting underway for the first cohort in 2017. The academic director of the fellows program, Mike Savage, stressed the goal of creating a truly interdisciplinary effort. “Inequalities are multidimensional, and narrow policy fixes—even radical ones—are unlikely to be sufficient to address the challenges involved. There is a need for future leaders to be informed by new research across a wide range of disciplines in order to address the challenge of escalating inequalities across the globe.”

Oechsli stressed this same point to me about collaboration in explaining the design of the new initiative. “This is not just about developing individuals,” he said. “It’s about helping individuals recognize that they are most effective when they collaborate with others.” Atlantic’s ultimate goal is to create, over time, a cohesive network of change agents who could impact the areas Atlantic has long cared about, especially health equity.

Maybe the best way to think about the Atlantic Fellows program is that it is melding the red-hot idea of collective impact with the more familiar idea of leadership development. Such a design isn't a new idea. The Robert Johnson Foundation, among other funders, has created similar programs. But never at this scale.

In the end, Atlantic's new thing sounds pretty cool. Let’s hope it works.

Related: A Closer Look at Atlantic's End Game—And Where It's Putting the Biggest Money