Why Are National Foundations "Edging Away" from Established New York City Arts Institutions?

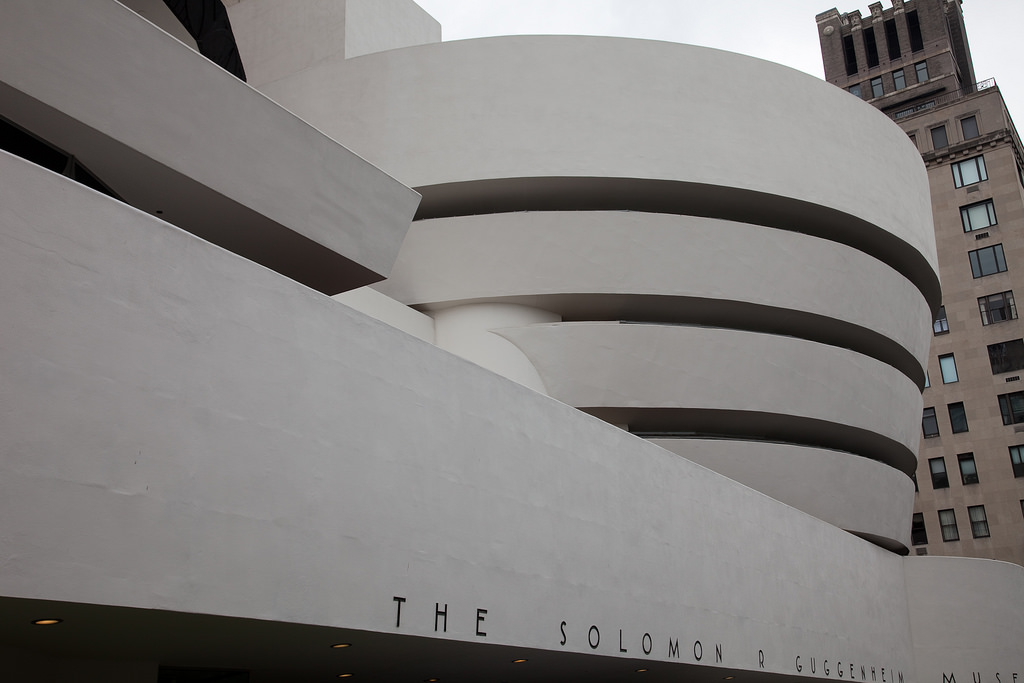

/The guggenheim museum

Last year, I wrote a piece titled "Will NYC's Arts Organizations' Collective Multi-Billion-Dollar Gamble Pay Off?" The answer at the time was: "If donors keep their wallets open, then probably."

What a difference a year makes.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art recently announced it is delaying its plans to build a new $600 million wing so it can get its finances in order. New York Philharmonic Director Matthew VanBesien announced his early departure, throwing a wrench in an already complicated $500 million mega-project. And last year, Carnegie Hall extended a drive to raise $125 million after it fell short of its initial goal.

Then there's the recent article by Adrian Ellis in Apollo Magazine whose title doesn't pull any punches: "Trouble Ahead for New York's Museums."

"After years of expansion," the teaser reads, "the financial pressures on New York's museums are greater than ever," due, in part, to the fact that national grantmakers are politely excusing themselves from the party.

It all presents the question: Why?

Before we seek an answer, let's first get a handle on a set of assumptions that are being demolished in real time.

One assumption is that while mega-projects are inherently risky, donors, particularly those in New York City, would inevitably step up. As Michael Hamill Remaley, senior vice president for public policy and communications at Philanthropy New York has noted, "The 1% is not hurting."

Of course, this premise remains true, and we've seen gifts that play into this narrative. Estate of Amber Lightfoot Walker, for example, gave $15.5 million to support New York City institutions like Lincoln Center Theater and the Morgan Library & Museum. Last April, David Geffen famously gave $100 million to the Museum of Modern Art. And yet, on the other side of the coin, billionaire collector J. Tomilson Hill started his own museum rather than donate the works to an established institution.

But individual donors are one thing. National funders are another beast entirely. And to hear Ellis tell it, the latter group is quietly making a beeline toward the door:

What about trusts and foundations? Many of the more established national foundations—Ford, Rockefeller, Pew, Gates, etc.—are edging politely but firmly away from what they now call "legacy" institutions that cannot demonstrate a significant contribution to solving or soothing specific social or economic traumas.

And there, dear readers, in one succinct paragraph, we see the ripple effect of two of art philanthropy's most timely trends that affect organizations regardless of their location: the rise of performance metrics and the idea that art should address social problems.

To the former, institutional donors increasingly want to see quantifiable bang for their buck. As repeatedly noted here on IP, this is bad news for organizations in the arts field, where communicating objective value is inherently difficult. And it's even more difficult for well-endowed institutions that—if we're to believe the prevailing stereotypes—cater to well-to-do clientele.

To the latter, ever since Ford pivoted toward combating inequality, other foundations have followed its lead. Art, the logic follows, must address some discrete social problem and foment action and change. Does a performance of "La Bohème" accomplish these goals? (I won't venture to answer this question.)

But, wait, there's more.

"Meanwhile," Ellis continues, "corporate philanthropy shriveled up in parallel with the intensifying search for shareholder value in the 1990s and early 2000s," before again bringing up the dreaded "m" word:

Corporate funding is accessible if and insofar as a cultural institution can demonstrate—with robust metrics—the contribution that sponsorship makes to the sponsor’s bottom line. This can be tough territory for the arts.

So the metrics craze is actually squeezing organizations from two sides: one, from foundations looking for a return on investment on an arts experience, and two, from corporate donors, who, while channeling their inner Milton Friedmans, care less about improving society and more about boosting shareholder value.

In a way, it's easy to feel a bit sympathetic toward many of these museums (irresponsible mega-projects notwithstanding.) They're beholden to dynamics beyond their control and entirely outside the purview of traditional arts management.