Disrupting Bail: An Innovative Criminal Justice Reform Idea Gains Momentum—And Funders

/photo: sakhorn/shutterstock

As funders rush to confront the immense injustices of American mass incarceration, bail reform has become a top priority on a very long to-do list. It’s not hard to see why. On any given night, nearly a half-million people wait behind bars—prior to any criminal conviction—often because they lack the funds to secure their release before heading to trial. Facing lost jobs, lost homes, and even loss of custody, many take plea deals rather than remain locked up, even if they didn’t commit the crime.

Serving as a public defender in the Bronx, Robin Steinberg came face-to-face with that catch-22 on a regular basis. It hammered home the vast difference that financial means make for those encountering the criminal justice system. Steinberg, who now heads the Bail Project, told me, “Years of standing next to people pleading guilty because they didn’t have 500 dollars in their bank account, even if they were innocent, brought to light how incredibly unfair the system is.”

Given its high degree of decentralization, changing that system is a herculean task. But a growing number of funders see the “front end” of the criminal justice system—including jails, policing and money bail—as the most promising place to focus resources. Those funders now include big legacy foundations like MacArthur and newer outfits like the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. Even Google’s getting involved.

But back in 2007, when Steinberg was running the Bronx Defenders—a public defense nonprofit she founded a decade earlier—that momentum had yet to gain steam. With a key initial contribution of $100,000 from music executive Jason Flom, Steinberg created the Bronx Freedom Fund with a simple idea: find people who couldn’t afford to bail themselves out, and do it for them. “At the time, we weren’t sure what would happen,” she said.

The logic behind bail is that it acts as “skin in the game,” guaranteeing the return of defendants to court. But as Steinberg suspected from the start, it isn’t really necessary. Of those the Bronx Freedom Fund bailed out, 96 percent appeared in court as scheduled.

That’s an impressive result. But what makes this model particularly exciting from a philanthropic perspective is its sustainability. Because bail is refunded when defendants successfully return to court, the same money can be used over and over again—two to three times a year, according to Steinberg. Effectively, that means $96,000 of Flom’s first contribution was back on hand after completing its initial work. Steinberg says some of that money still revolves to this day.

If bail isn’t making defendants return to court, what is? According to Steinberg, the vast majority of people simply recognize that coming back is in their best interest. Missing a court date can result in a warrant, and stiffer penalties down the line. “All that’s necessary,” she said, “is to have an effective way to notify someone about their court date. But living in poverty makes that hard.” At the same time, she’s keen to avoid the onset of alternative surveillance methods, including electronic tagging, where “one system of oppression is taken over by another.”

When a revolving fund bails defendants out and lets them return on their own, Steinberg says, case dispositions are dramatically impacted. Without the option to hold plea deals over defendants' heads, prosecutors tend to dismiss cases a lot more frequently. That can catalyze a virtuous cycle in which district attorneys, for instance, indicate to police that they won't bother prosecuting certain low-level cases.

Related: With the Backing of Top Funders, This Group is Taking the Criminal Justice System to Court

Given the Bronx fund’s success, Steinberg and her colleagues wanted to scale up the model. A national fund—or a network of local funds operating in different cities—would help more defendants and build momentum for wider challenges to money bail. Indeed, over the past five years, independent community bail funds have popped up in Seattle, Boston, Baltimore, and elsewhere. The idea behind the Bail Project (a separate organization from the Bronx Freedom Fund) is to elevate that ecosystem and start bailing people out in cities the community funds don’t already cover.

The Bail Project is quite new: It officially began its work last year. But it has already raised $30 million of a $52 million goal. Given that level of funding, the organization anticipates operating in 40 sites and bailing out 160,000 people over the next five years. January saw the project begin operations in Tulsa and St. Louis, with an effort in Louisville launching this month. Detroit is next on the list, slated for June, with Dallas following shortly after.

So who’s funding The Bail Project? For one thing, Steinberg and her team are busily soliciting small donations from the public, all of which go toward bailing people out. Larger contributions cover operating costs as the project expands. Among those bigger commitments are funds from a number of family foundations as well as sizable support from investor Michael Novogratz, who serves as chairman of the board.

In a recent profile in The New Yorker, Novogratz characterizes the Bail Project as a “radical move.” He echoes another point that came up frequently in my conversation with Steinberg: the collateral consequences of pretrial detention. “We know the first three to five days in jail are the most damaging,” Novogratz said in the piece. He lists sexual assault, job loss, and suicide as only a few of the potential dangers.

Richard Branson has also donated to The Bail Project, as has the Bronx Freedom Fund’s initial benefactor Jason Flom. But the initiative’s largest source of support is TED, of all places. Specifically, the Bail Project is one of seven initial grantees receiving money and a platform from the Audacious Project, a philanthropic venture from the organization that brought us TED Talks that debuted earlier this year. There’s quite a bit of money involved. So far, Audacious has raised over $400 million from big names like Gates, Skoll, MacArthur, and Dalio.

Related: The Audacity of TED: New Platform is Moving Big Money, But Does it Get Social Change Right?

As we noted when we covered TED's initiative, this “venture philanthropy” approach comes with its own set of issues, including a persistent tendency to overestimate what entrepreneurial ideas can accomplish by themselves. But for underdog causes like ending money bail, the Audacious Project offers a big stage—literally. And Steinberg was quick to remind me that criminal justice reform will take a village.

She seems mostly optimistic about the possibilities for progress in an area that’s long stymied reformers. “I like to think that as a nation, we’ve reached a tipping point. People have been toiling away at the community level, the policy level, the legal level for decades. That chorus of voices finally became so loud and clear that people are listening,” she said.

Bail reform is part of a wider constellation of criminal justice reform efforts, each operating in its own wheelhouse. Civil Rights Corps is one example. As we recently reported, that small shop of activist attorneys has already notched several wins against the bail system in local and state courts since it got started two years ago. Its backers include the Sandler Foundation, the Laura and John Arnold Foundation, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and the Open Philanthropy Project.

Along with the Pershing Square Foundation and an array of big names like Ford, MacArthur and Open Society, some of those funders are also supporting Measures for Justice, a bid to collect and centralize data on America’s diffuse criminal justice system. As Steinberg confirmed, a lack of clear data is one of the main factors holding back reform. Indeed, the Bail Project sees data collection as one of its key roles, to furnish systemic reformers like Civil Rights Corps with evidence that the system can and should change. The Misdemeanor Justice Project is another initiative working on the data problem.

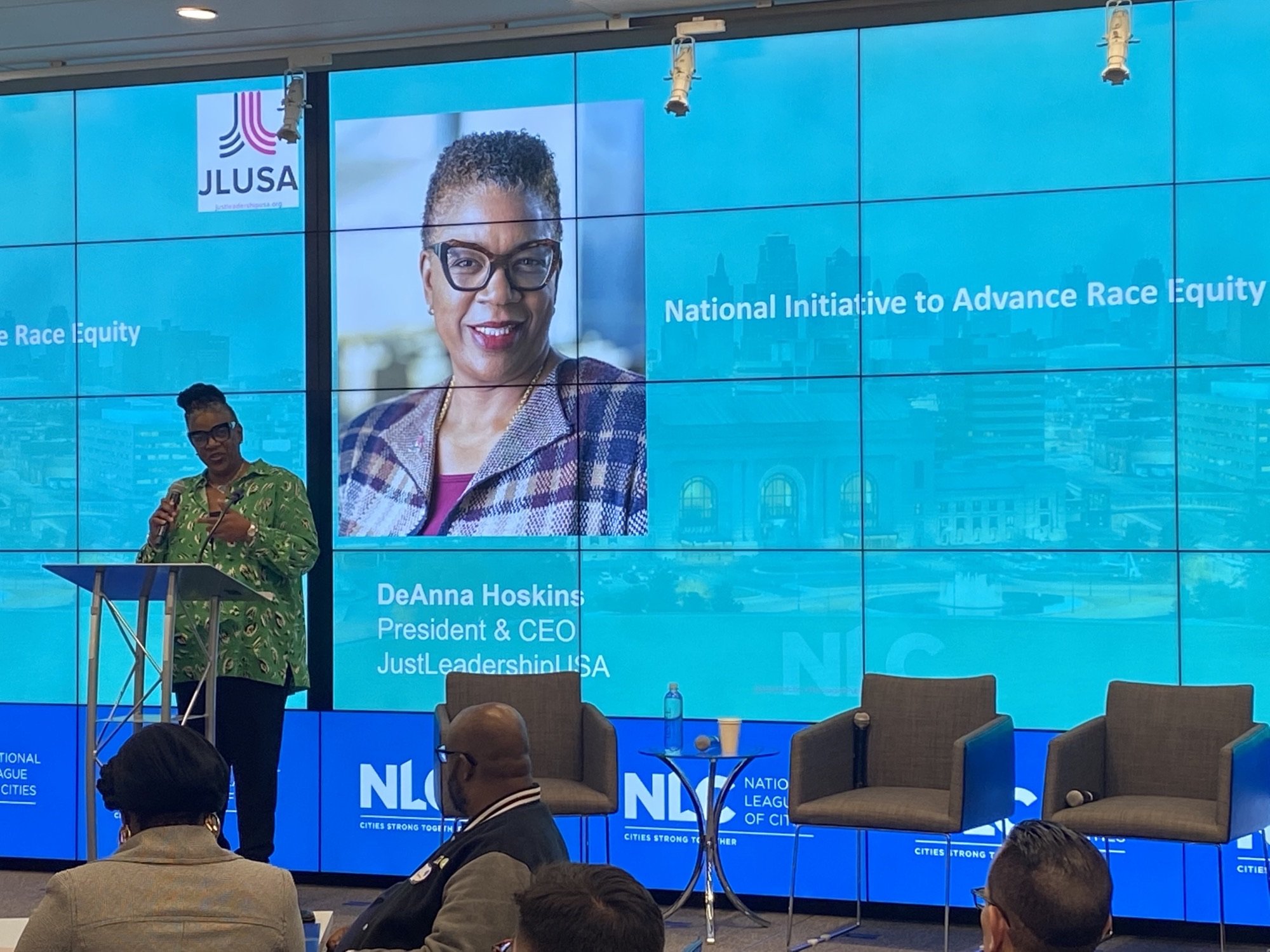

At the same time, The Bail Project is also trying to elevate voices from communities disproportionately impacted by pretrial detention, and to give them concrete roles in the fight to end bail. Steinberg has already hired several “bail disruptors” with past experience in the criminal justice system. The disruptors operate in their home cities, partnering with local advocates and public defenders to identify potential clients. Meanwhile, national criminal justice reform organizations like JustLeadershipUSA and Families Against Mandatory Minimums have taken similar community-centered approaches.

Restoring agency back to those who’ve had it taken from them lies at the heart of what the Bail Project is trying to accomplish. Steinberg told me, “Cash bail in this country is a way we criminalize based on race and class... It calls into question the legitimacy and fairness of the entire system.” As bail disruptors get to work in a widening network of cities, the Bail Project’s philanthropic backers may have found a leverage point that’ll catalyze real systemic change—while also serving people on the ground, over and over again.

Related: