Backing Up Biden: Grantmakers Get Behind a New Federal Anti-Violence Collaborative

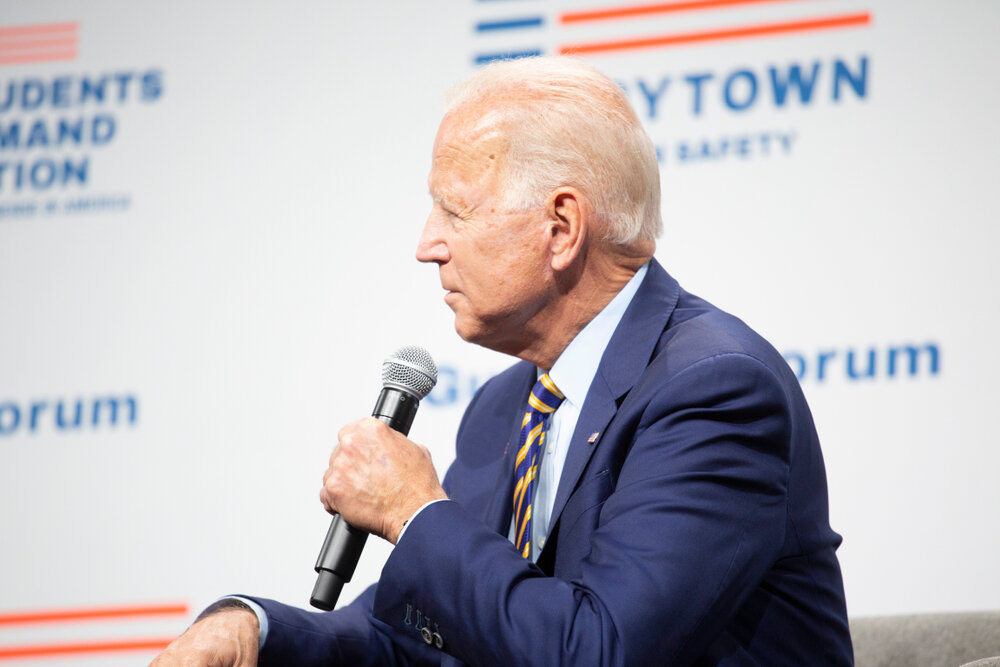

/Biden speaks at a gun violence prevention event. Photo: CJ Hanevy/shutterstock

Violent crime has trended downward for decades, and it’s been an issue of only moderate importance for philanthropy at large. But that may be changing. Rates of homicide and other violent offenses are still nowhere near their late 20th-century peak, but a troubling upswing is now underway.

According to preliminary data from the FBI, the nationwide murder rate rose by 25% or more from 2019 through 2020, putting the total number of homicides at around 20,000 compared with 16,425 in 2019. And even as overall crime fell during the pandemic, violent crime went up by around 3.3%.

The social and political implications are still uncertain, as is the degree to which circumstances like the pandemic, racial justice and anti-police protests, and an uptick in gun sales factor in. But on the streets of U.S. cities—and in underserved Black and Latino neighborhoods in particular—those statistics reflect a human toll that’s unheard-of in most other wealthy nations.

Last week, the Biden-Harris administration announced what it calls “a comprehensive strategy to combat gun violence and other violent crime” that will draw on American Rescue Plan (ARP) funding to implement a range of strategies to reduce crime, with an emphasis on tackling gun violence. Among them is a new collaborative of 15 local jurisdictions that’ll use federal funds and other support to expand commitments to community violence intervention (CVI).

Notably, this new CVI collaborative will enlist the aid of a sizable group of philanthropic funders, including some heavy hitters in the criminal justice and violence prevention space. It’s a diverse list, comprising legacy foundations like Ford and MacArthur, grantmakers headed by big donors like Arnold Ventures and the Emerson Collective, and even one corporate funder.

It’s also unusual. Public-private partnerships involving philanthropy are quite common on the state and municipal level, but it’s rarer to see private grantmakers aligning their efforts so closely with a federal administration. Nevertheless, liberal funders haven’t been shy about backing up Biden.

But what exactly is community violence intervention, and why might it lend itself to such a high-profile collaborative effort?

Reaching those most at risk

“Imagine living in a country where, if you had two sons, there would be a 1-in-20 chance one of them would be shot before he’s out of his teens.” That’s from a report the Biden administration cited in its announcement, compiled by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence and the PICO National Network. It describes a situation common in some majority-Black neighborhoods, where homicide rates can exceed the national average by a shocking 20 times or higher.

In essence, community violence intervention strategies act as an alternative to heavy-handed policing by focusing on the specific set of people—usually a very small number of youth and young men—who are either perpetrators or targets in the vast majority of a given neighborhood’s violent crime. Some CVI methods involve the police, but at their core is a commitment to reaching those young men through other channels, i.e., through local organizations embedded in the community or with the help of “violence interrupters” with street connections who can engage with at-risk individuals personally.

There are several strands of CVI practice, all detailed in greater depth in the Giffords Law Center report. One is group violence intervention (GVI), in which credible community members work with law enforcement to identify specific individuals most at risk and engage them in meetings, or “call-ins,” to communicate the message that the violence must cease.

The “cure violence” method treats violence as a communicable disease and works to interrupt its transmission via the cycle of retaliation. This is where those violence interrupters come in. At the risk of straining the analogy, they act as a kind of anti-violence immune system, more effective than the distrusted police because they’re more credible. There are also hospital-based interventions, which engage at-risk individuals during a highly teachable moment—when they’re actually recovering from a gunshot or other wound.

These methods aren’t mutually exclusive. But they’ve often been highly effective at reducing violent crime. According to the Giffords Center report, the GVI method has a documented association with reductions in homicide of between 30% and 60% in specific jurisdictions. And in New York neighborhoods implementing cure violence methods, homicide dropped by 18% over three years while similar neighborhoods experienced a rise in murder rates.

Back in April, the Biden administration leaned heavily into CVI, announcing a plan to invest in the practices across a wide range of federal grant programs at the Department of Justice, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Department of Education and the Department of Labor. The new philanthropy-backed CVI collaborative is another sign of the administration’s eagerness to adopt these methods.

A who’s who of violence prevention funders

So who’s actually in the collaborative, and what are its plans? To begin with, the collaborative itself comprises 15 local jurisdictions that are pledging to use a portion of their American Rescue Plan funds or other public dollars to beef up CVI initiatives, including in anticipation of a summer surge of violence. The list of locations spans the country.

Over the next year and a half, the Biden administration will advise and assist local officials in their efforts. Philanthropic funders that the administration calls “leaders on this issue” will deploy experts to provide assistance, incorporate public health approaches into the work and help local organizations scale their CVI programs.

The funders involved include the California Endowment and the Annie E. Casey, Ford, Joyce, Kellogg, Kresge and MacArthur foundations. Some grantmakers headed by living donors have also signed on, including Arnold Ventures, the Emerson Collective, the Heising-Simons Foundation, the Open Society Foundations and Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies. One corporate grantmaker is also on the list—Microsoft.

Most of these funders have been active on the criminal justice reform front for some time. They’re also backers of violence prevention work, including nonprofit efforts to hold the epidemic of gun violence in check. It’s unclear at this early stage exactly who will do what, but several are already supporting CVI strategies and the community nonprofits implementing CVI on the ground. Others have given more for research and policy.

Several funders on the list focus their violence intervention support on specific locales. For instance, the Joyce Foundation supports CVI methods in the Great Lakes region through its Building Safe and Just Communities program. CVI is actually a new addition to Joyce’s work, and the foundation hopes to expand the community of practitioners and back research and advocacy for public sector adoption of CVI techniques. Needless to say, this partnership with the federal government ticks a lot of those boxes.

The MacArthur Foundation is another justice reform stalwart with a local focus in Chicago, where it supports organizations leading the charge on CVI, like the Institute for Nonviolence Chicago, New Life Centers of Chicagoland, Claretian Associates and UCAN—all of which are associated with the Partnership for Safe and Peaceful Communities, of which MacArthur is a major supporter.

The Annie E. Casey Foundation has also stepped up its funding for CVI efforts in recent years. “Violence is a public health matter,” said Amoretta Morris, director of national community strategies, in a recent post on the foundation’s blog. Annie E. Casey has backed CVI methods like the cure violence model in Baltimore, Milwaukee, Baton Rouge and Atlanta. It’s also supporting the Health Alliance for Violence Prevention, a key practitioner of the hospital-based intervention model.

Microsoft, meanwhile, is supporting this work through its Justice Reform Initiative. Although that component of the company’s philanthropy began before George Floyd’s murder and the uprisings that followed, it got a five-year, $50 million boost last summer. Policing and prosecution reform are both priorities for Microsoft’s initiative, as are diversion methods and alternatives to policing like CVI, which Microsoft has backed through organizations like the National Network for Safe Communities.

While many of the nonprofits spearheading CVI have a local focus, some operate across multiple jurisdictions, and they’ll likely receive support through the CVI collaborative. On top of those already mentioned, others include the California Partnership for Safe Communities, Cure Violence, the National Network of Hospital-based Violence Intervention Programs, the PICO National Network and PICO’s Live Free Campaign.

One of several public-private partnerships in the works

In one of a flurry of statements from funding leaders accompanying the collaborative’s debut, Laurene Powell Jobs mentioned the Emerson Collective’s support for CVI efforts through the organization Chicago CRED. She went on to note that “we understand that the work of curbing violence and healing communities depends on close collaboration between the public and philanthropic sectors.”

It’s rare to hear much from Laurene Powell Jobs, and it’s also rare to see philanthropy associating this closely with a federal administration. It speaks to the administration’s faith that private grantmakers can bring connections and expertise to bear that’ll still be valuable despite much vaster public allocations of cash.

That federal cash may be substantial. A portion of the ARP’s $350 billion state and local funding can be dedicated to CVI, as well as part of the ARP’s $122 billion in K-12 education funds. The administration has also proposed another $5.2 billion of dedicated CVI funding as part of the American Jobs Plan—far more than philanthropy will realistically bring to the table.

Though the administration’s announcement doesn’t mention it, there is an interesting outfit facilitating the entire effort on the nonprofit side. It’s called Hyphen, and it was founded by Obama administration alum Archana Sahgal with a very specific mission: “to methodically engage the Biden-Harris Administration in building public-philanthropic partnerships that benefit marginalized children, families and communities.”

As a 501(c)(3) intermediary, Hyphen will act as an “anchor” for the collaborative. Hyphen itself receives support from Panorama Global, a 501(c)(3) “action tank” that oversees a number of entities including the Ascend Fund, seeded by Melinda French Gates in 2019 to advance women in U.S. politics. Panorama’s founder, Gabrielle Fitzgerald, previously worked for the Gates Foundation.

Hyphen’s projects don’t end with the CVI collaborative. It has multiple irons in the fire, including a bid to convene funders around Biden’s executive order on racial equity, another to spread the word about COVID vaccination in the South, and support for the FWD.us Education Fund’s National Dignity for Families Fund, launched earlier this year to provide aid to refugees seeking asylum in the United States. Hyphen also says it’s working more broadly to align philanthropic funders with the ARP.

For the time being, it looks like the CVI collaborative and Hyphen’s other projects are mainly about connecting philanthropy with Biden objectives in areas of direct service and ground-level implementation—that is, not in the realm of policy. But policy does hover in the background.

For instance, while the Biden administration hasn’t couched the CVI collaborative in language specifically referring to guns, firearms are used in around 75% of U.S. homicides as of 2019. It makes sense that much of the administration’s recent announcement—parts not concerned with CVI—focuses on the problem of taking action on gun violence without congressional legislation. Many of these philanthropic CVI funders are also backing research and policy work to curtail gun violence.

It’ll be interesting to see how this unusual public-private collaborative actually functions, what it can accomplish in terms of reducing violence, and how far, if at all, these new efforts to marry philanthropy and Biden objectives will extend into the realm of policy.