Personalized Learning Is a Big, Exciting Idea. But Can Funders Like Gates Get It Right?

/Unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past few years, you’ve probably heard something about the concept of personalized learning. The idea behind personalized learning is that America’s traditional one-size-fits-all approach to education is failing our children. Every kid is different—they have different strengths and weaknesses, they have different interests, and they absorb information differently.

One of the most interesting facets of the personalized learning movement is that it didn’t start in classrooms. In fact, a group of philanthropic foundations and advocacy groups, with contributions from educators, have taken the historically European concept and adapted it to their own working definition of what personalized learning should look like in America. As the Gates Foundation puts it:

Personalized learning is an educational approach in which teachers and schools create systems, tools, and methodologies that tailor instruction to the individual needs, skills, and interests of each student, in an effort to accelerate and deepen learning.

The ed reform community has been all over personalized learning in recent years. Millions of dollars, both private and public, are being poured into schools experimenting with a personalized learning approach. In 2012, the federal government doled out over $380 million in grants to schools committed to adopting the approach. But with the definition of personalized learning still blurry to most, the extent of private giving, while easily in the tens of millions, has been a little more difficult to pinpoint.

In fact, a Google search of "personalized learning" produces hundreds of articles looking at this concept from different angles.

In an attempt to bring more clarity and cohesion to this emerging ed field, the Gates Foundation, Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation and the Michael & Susan Dell Foundation got together with the Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, Charter School Growth Fund, EDUCAUSE, and the Learning Accelerator, among others, to map out what a personalized learning approach should look like.

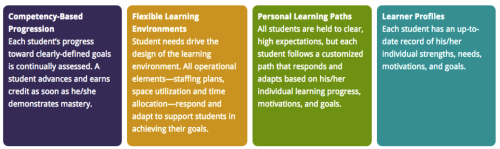

This is what they came up with:

Sounds like great stuff, right? But lots of ideas for improving education have sounded appealing, while failing to work out in practice. Ed philanthropists have learned that the hard way, again and again, pouring money down different black holes. This is a notoriously complicated funding space in which many have tried and failed to make things better.

The Gates Foundation itself has experienced its share of disappointments, so you can imagine why it really wants to get things right with a big, exciting idea like personalized learning.

To do that, Gates commissioned RAND to conduct ongoing research to ensure that any move toward personalized education funding is backed up by solid research and measurable results. The series of reports is intended to help identify the most promising and important features of personalized learning models, to document the challenges schools face in implementing these models and to learn which components of personalized learning are most critical in the success of these new models of teaching and learning.

According to the first Interim Research on Personalized Learning report released last fall, there is reason to be optimistic:

Although results varied considerably among the 23 schools in this study, two-thirds of them had statistically significant positive effects on students’ math and reading scores. Moreover, students generally ended the school year with math and reading test scores above or near the national average, after having started the school year generally performing below the national average

Although the specific features of the personalized learning models the schools use vary, each school in this study is implementing one or more key personalized learning practices: learner profiles, personal learning paths, competency-based progression, and/or flexible learning environments.

It’s important to note that the 23 schools in the study—all which receive funding from the Gates Foundation to implement personalized learning practices—are charter schools, which raises a slew of other questions related to a whole other debate that we’re not going to touch right now.

So far so good with personalized learning, overall, according to the super-wonks at RAND. But the more notable takeaway, here, may be that ed reformers have learned some lessons about what it means to change the landscape of education in the United States. Innovating is hard, and reformers have taken some hits after backing ideas or initiatives too early, before they're fully baked.

So now, this time around, big ed funders appear to be playing it cautious, awaiting proof-of-concept before going all in.