Unpacking a Partnership: A Museum Nets a Historic Windfall. But at What Cost?

/

Loyal readers of IP's visual arts space know we've devoted a lot of ink to the increasing importance of contemporary art and the whims of its donors.

The narrative goes like this: There's a huge demand for contemporary art. When museums attain such work, that's a good thing. But sometimes donors would rather open their own galleries, and that's a bad thing because it exacerbates scarcity, further driving up prices.

But news out of the Bay Area, courtesy of the San Francisco Chronicle's Charles Desmarais, surfaces a third, more ambiguous and slightly Faustian scenario: A donor willing to contribute highly valuable art but with massive strings attached such that it may compromise the integrity of the museum.

Let's set it up for you.

Back in 2005, Donald Fisher, a billionaire retailer, philanthropist, and one of the world's most prominent art collectors, contacted the head of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and proposed a Fisher Wing that would house the collection of contemporary art Fisher had built with his wife, Doris, over the past 40 years. Neal Benezra, director of the museum then and now, turned down the offer. "What Don was offering was, on the one hand, extremely generous," he said in a recent media interview. "But Don wanted something that I felt we couldn’t offer him...a kind of curatorial control over what got shown."

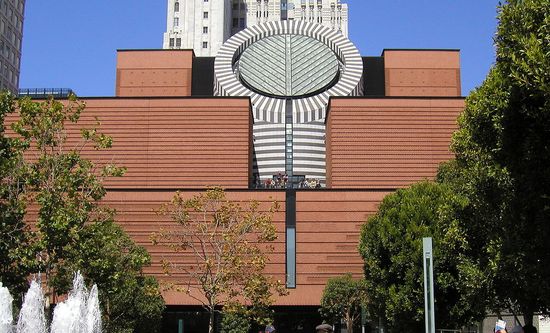

Fast forward to 2009. Proving that the second time's a charm, an ailing Fisher and the museum were able to hammer out an agreement, resulting in the extraordinary new building and the Doris and Donald Fisher Collection Galleries.

At the heart of the Chronicle piece is a thorough examination of the 2009 deal, and with it, questions around the level of influence private collectors exert over public institutions. We've taken the liberty of distilling the Chronicle's assessment of the deal into three key elements. The first, and seemingly least portentous, is a stipulation that any loans of Fisher works to other institutions must be approved by the Fishers.

A second and somewhat related detail involves the actual ownership of the work itself. According to the Chronicle, most of the art, in fact, belongs to Doris Fisher alone while the museum' partnership is with an entity called the Fisher Art Foundation. And so Desmarais can't help but rightfully ask:

One work or two might have little effect on the overall collection; but what if she, or some heir in the decades ahead, asks for hundreds of works back? While that could put a crimp in the museum’s long-range plans, other aspects of the partnership recently unearthed appear to be far more disconcerting for us, the audience.

All of which brings us to the final—and potentially most impactful—components of the deal, components that will inevitably affect the museum's relationship with and committment to the community at large.

The museum has agreed to display no more than 25 percent of works from other lenders or donors in the Doris and Donald Fisher Collection Galleries on the fourth, fifth, and sixth floors. This means that the museum has to display the collectors’ works in about 60 percent of SF MoMA's indoor galleries for the duration of the loan, which ends in May 2116, but can be extended in twenty-five-years increments.

Calling the gift a lose-lose for the museum, its audience and potential benefactors, cultural critic Lee Rosenbaum said:

Tying SFMOMA’s hands for 100 years and hogging so much of its space (25%, at most, of the three-floor expanse of Fisher-named galleries to be allocated to works from other lenders or donors) is an excessive concession, even if the Fisher trove were a permanent gift, not merely a long-term, renewable loan. These restrictions, assuming Desmarais’ report is accurate, would turn the new Snøhetta-designed building into a Fisher fiefdom.

Then she twists the knife: "What other collector would want to make major art donations to SFMOMA under these fishy Fisher circumstances? No wonder the museum was reluctant to divulge the full terms of this deal: Its windfall could become its downfall."

Desmarais is a bit more even-handed, rightly noting that single donor-focused museums and galleries have existed for a long time and that most directors would happily sign on to the Fisher deal, especially given the sector's unquenchable thirst for contemporary art.

To that end, MOMA's plight doesn't exist in a vacuum. An ever-growing body of research suggests that mega-donations to mega-museums create mega-problems, not just for the recipients on the hook for downstream costs, but smaller organizations vying for ever-shrinking public dollars. Click here for more for (somewhat depressing) analysis along these lines.