To Guide Hilton's Global Giving, CEO Peter Laugharn is Drawing on Lessons He Learned in Mali

/gaborbasch/shutterstock

When thinking about global development philanthropy, the Conrad N. Hilton Foundation isn’t the first name that leaps to the mind. Its endowment of $2.8 billion is smaller relative to the heavy hitters; its leaders are low-key and less hungry for media attention; and perhaps its sprawling ambit in the past diluted the impact of any single program.

However, since 2016, Peter Laugharn has been at the helm, and one of his first moves was to streamline the foundation’s focus from eleven to seven priority areas, four of which are focused on global development: Safe Water, Young Children Affected by HIV/AIDS, Disaster Relief and Catholic Sisters. The foundation’s endowment is also expected to double, as Barron Hilton, Conrad Hilton’s son, has pledged 97 percent of his fortune upon his passing. This will make it larger than the Rockefeller Foundation.

But what really stands out is Laugharn’s philosophy of global development grantmaking, which is shaped by his experience as both a doer and donor. Before coming to Hilton, Laugharn led the Firelight Foundation, which supports community-based nonprofits in Africa, and earlier, worked for 11 years on children’s education issues for Save the Children in Mali.

His experience in Mali left him with a deep appreciation of the power of poor communities to transform their own lives. “I have a strong conviction that there is a lot of solidarity and capacity at the local and community level in African societies,” he told me in an interview.

Laugharn is passionate about “localizing” global development philanthropy. He says the problem with a lot of giving in this space is “how much evaporates when you make grants to international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) before the funds reach the local level. It has to go through global headquarters, then the capital, and finally to the community level.” Laugharn saw how things could be done differently at the Firelight Foundation, with its direct support of local groups in Africa, and he’s sought to bring that mindset to Hilton, where the staff has been discussing ways to localize the foundation’s global grantmaking. Laugharn says that’s not an easy shift, given the challenge of identifying and targeting community groups, and that they would probably have to use “intermediaries” such as Firelight, who then re-grant to community-based groups.

Laugharn worked in Mali around the time when governments were signing on to the Education for All initiative—an experience that shaped another belief: “That the presence of a goal really gets your juices flowing.” All of Hilton’s global development programs are explicitly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 2030 agenda—an approach adopted by the former director, but one that resonates strongly with Laugharn’s worldview.

His time in Mali also fueled his understanding that long-term sustainability and systemic change requires integration with local and national governments. “Many of the goals in the SDG agenda are extremely challenging and will produce a lot of value at the individual, family, local and national level, but they can only be addressed robustly with the involvement of local and national government,” he said.

HIV-Affected Children

The foundation’s program on HIV-Affected Children, which adopted a new strategy in 2017, reflects Laugharn’s vision, especially his interest in systems-level change and working with government. The program addresses early childhood development (ECD) for HIV-affected children, making Hilton one of the few global funders to integrate ECD with HIV in its grantmaking—and is explicitly aligned to SDG 4 on education. It also emphasizes the first 1000 days of child development, especially nutrition interventions, “given how important nutrition is for ECD and its contribution to the reduction of stunting.” Grantmaking is focused on countries in Africa with a high prevalence of HIV: Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zambia.

The program is funding and testing a variety of approaches, both at the household level and at the government level. What’s refreshing is Hilton’s admission that it doesn’t yet know which interventions work in its selected countries. The strategy reflects the ideas of those who argue that development’s “wicked problems” require a complex systems approach in which a portfolio of interventions is launched and tested simultaneously, and “adaptive learning” occurs in real time. Some of the interventions are: improving child feeding practices through breastfeeding and home gardens, the WHO/UNICEF Care for Child Development (CCD) package, and using the national, community health worker infrastructure to deliver ECD coaching and messaging.

Despite Laugharn’s rhetoric about the importance of localizing philanthropy, in 2017 and 2018, grantmaking in this program still reflected a bias toward large international NGOs and U.N. agencies. PATH was the biggest grantee, pulling in $8.2 million. Other top recipients included United States Fund for UNICEF ($4 million), Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation ($2.7 million), and UCLA Center for World Health ($2.6 million). South African Stellenbosch University, which received $2 million in grants, was the only Africa-based organization that was among the top five recipients.

Safe Water

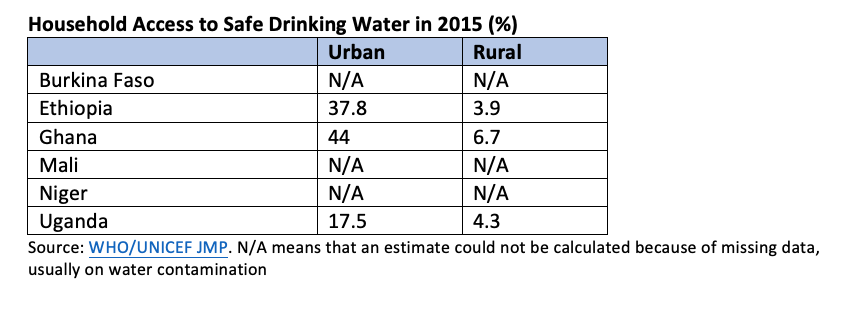

Hilton has been committed to increasing access to safe drinking water in low-resource settings for 25 years, and its new strategy, adopted in 2017, also reflects Laugharn’s emphasis on systems and government. The program—aligned to SDG 6 on water and sanitation—aims to increase access to safe and affordable water for households, schools and health facilities in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mali, Niger and Uganda.

The WHO/UNICEF data on household access to safe water in Hilton’s focus countries in 2015, collected before the launch of the SDG agenda, underscores the gargantuan challenge for all SDG 6 donors:

Laugharn is the first to concede the scale of the foundation’s ambition in this area, and the strategy notes that donors “cannot continue to conduct business as usual.” For Laugharn, this means “moving from a focus on wells and boreholes to a systems-based and sustainable approach,” as well as a willingness to tolerate more risk.

As with the HIV-Affected Children program, the “systems-based approach” requires robust government engagement at all levels. “These problems cannot be solved with international NGOs focused on five-year projects,” Laugharn said. “But it is daunting because these systems are not well developed. And it is also not the sexiest topic to talk to boards about.”

The call to tolerate more risk specifically means moving beyond “established” international NGOs and experimenting with partners and approaches that may not be proven, but have the potential to deliver greater impact. Again, Hilton’s water strategy is notably humble, conceding that the foundation doesn’t yet know how to achieve its objective, but is committed to experimentation, learning and adaptation.

Like the HIV-Affected Children program, the top-five dollar value grants in 2017 and 2018 still reflected a bias toward northern-based NGOs. The biggest grantee, with $7.6 million in funding, was the IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, along with major support for World Vision and Water.org. But here, Hilton has managed to move beyond the usual suspects to channel substantial grant money to less widely known NGOs such as Splash International and the Aquaya Institute.

Disaster Relief

Laugharn is also guiding revisions to the foundation’s Disaster Relief program. Because events of the past few years suggest that calamitous disasters are increasing in frequency, intensity and scale of impact, in 2018, the board voted to expand this program and a new strategy will be released in December 2019.

The program increases the foundation’s attention to refugees, and its two highest-value grants over the past two years reflect this interest. In 2017, Save the Children received $500,000 to support education interventions for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. In 2018, Hilton donated $500,000 to BRAC USA, the American subsidiary of BRAC—an international development organization based in Bangladesh that provides services to the poor in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean. The grant is intended to support the now 1 million Rohingya refugees that have fled persecution in neighboring Myanmar. The program invests in innovative approaches such as direct cash transfers to refugees.

As with the other programs, Laugharn hopes to localize disaster relief grantmaking. The foundation has accomplished this in its response to U.S. disasters. After Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Harvey in Houston, and Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, Hilton granted to community foundations that were closer to the problem so that they could re-grant to community-based organizations. Laugharn’s challenge for the future is applying this model globally.

Catholic Sisters as Human Development Leaders

The foundation still awards the biggest share of its grantmaking to the Catholic Sisters program. In 2017 and 2018, about $34 million of about $227 million in total grants went to this program. Conrad Hilton’s will specified that sisters receive “the largest part” of the foundation’s funds. Laugharn says that Hilton was educated by Catholic sisters, and also knew that they “would go where no one else wanted to go.”

The program’s new strategy, released in 2018, eliminated the distinction between its Global North and Global South work and targets the Americas, Europe, India and Africa. The program calls for the sisters to become human development leaders, and is also aligned with SDG goals one, two, three, four, five and eight, which target poverty, hunger, health, education, gender equality, and decent work. The strategy is explicitly anchored in the evolving doctrines of the Vatican under Pope Francis, noting his call for religious women to “care and support those in the margins” and the 2016 creation of the Vatican’s Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, focused on the marginalized, the sick, the poor and migrants.

The program’s highest-dollar-value grantees in 2017 and 2018 reflected this strategic focus on human development. In 2017, Catholic Relief Services received a grant of $2.7 million to strengthen the role of Catholic sisters in ECD programs. In the same year, the School Sisters of Notre Dame received $1.5 million to increase the engagement of Catholic sisters at the United Nations.

Localizing Philanthropy?

Laugharn’s desire to direct more of Hilton’s global development grants to local organizations reflects a larger conversation in development aid, in which participants increasingly call for both public and private donors to shift from treating actors in the Global South as passive beneficiaries to empowered decision-makers. Currently, local actors receive only 0.3 percent of humanitarian aid and 3 to 5 percent of development aid, according to this 2019 report by the Global Fund for Community Foundations.

Laugharn thinks there are a couple of reasons why foundations boards can be reluctant to move in this direction. First, they are often deeply invested in due diligence processes. With one of the mechanisms of foreign grantmaking—expenditure responsibility, as opposed to 501(c)(3) equivalency determination—the foundation is “on the hook” for the use of funds and may incur certain penalties if funds are misappropriated. Second, boards often prioritize rigorous monitoring and evaluation processes, and they may feel that international NGOs are better placed to perform these functions.

But Laugharn speaks again from the perspective of his experiences in Mali: “What keeps funds safe is not the books; it is the community’s eyes.” Perhaps more importantly, to borrow the economist William Easterly’s distinction, what makes funds work is if the local “searchers” at the bottom are allowed to set the agenda, and not the “planners” at the top of the mountain of money.