Quantitative Advocacy: How an Effective Altruist Funder Backs Criminal Justice Reform

/Criminal justice reform is a growing priority among funders these days, and strategies abound. But one common thread is backing rational assessment and evidence-based solutions to improve a flawed system that causes enormous societal harm. In that sense, the work of many justice reform funders tracks well with the ideas of effective altruism, which looks to deploy philanthropic dollars in clear-eyed and cost effective ways.

The Open Philanthropy Project is a leading proponent of this giving philosophy, and criminal justice has been on its agenda from the start. Shortly after it was born from the joint ambitions of GiveWell and Good Ventures in 2014, OPP learned from conversations with policy experts that the U.S. might be on the verge of a unique moment of possibility for criminal justice reform. Fast-forward to today, and OPP now ranks among the top funders targeting the issue, along with MacArthur, Ford, Arnold Ventures and the Open Society Foundations.

OPP has provided or recommended grants totaling over $70 million toward criminal justice reform since its inception. Where’s that money going? And what is OPP’s overarching strategy?

Following the Numbers

Chloe Cockburn, who heads OPP’s criminal justice reform portfolio, says about its grantmaking, “Ultimately the goal is cutting the flood of people into jails and prisons in favor of more effective public safety approaches, and cutting the needlessly long sentences that people are serving in jails and prisons… we think there are substantial opportunities for change right now.”

While many of OPP’s grantees receive support from other funders that are also looking to reduce mass incarceration, its approach is distinct. For one thing, it applies a formula to its grants to quantify their expected effectiveness. “We have a clear definition of how we calculate value in a grant,” Cockburn said. According to an extensive strategy summary, OPP calculates grant amounts by multiplying the “number of prison-years averted” by $50,000 (“our valuation of a year of incarceration averted”), and then dividing the result by 100 (“we aim to achieve at least 100x return on investment”).

On top of that, Cockburn said, OPP evaluates funding opportunities “in terms of expected value—where a 10 percent chance of achieving $10 million in value is worth $1 million. Putting these together, we are able to take on investments with a significant risk of failure if the upside is big enough, and we have a decent sense of whether we are on track or not.” OPP’s framework also gives it a quantitative rationale to “comfortably pass on grants that may seem appealing, but where the marginal return on our money isn’t worth the while.”

OPP acknowledges the difficulty of tracing how a given grant conforms to expectations. But while such a detailed quantitative approach to a problem like justice reform is rather rare, it’s not necessarily misplaced. Data gathering is one common vector for justice reform grants, and the promise of cost savings is a popular messaging point.

Also distinguishing OPP’s grantmaking is the attention it pays to public safety, a factor it says is often missing from the discussion. According to its evaluation of the field, the criminal justice system justifies punitive practices by citing individual and community safety. But it often fails to enhance actual public safety, e.g., by saddling large numbers of Americans with arrest records that make it hard for them to find employment, increasing the chances of future offenses.

Philanthropy’s attempts to elevate safety in the discussion aren’t limited to OPP. MacArthur’s Safety and Justice Challenge comes to mind, and gun violence prevention funders often talk about gun safety as a more palatable goal than “gun control.” Nevertheless, it is true that policy discussion of crime and violence often revolves around what some advocates refer to as “retribution” rather than what it should be about—making people safe.

OPP’s explicit attention to cost-effectiveness and public safety both have bipartisan appeal. After all, who could argue with making people safer and saving money? Action on justice reform from right-leaning funders like the Charles Koch Foundation—as well as the bipartisan passage of the First Step Act late last year—underscore the new political possibilities.

OPP is keen to seize on the moment by bolstering advocacy efforts across the U.S. “We look for leaders that are seeking to restructure the political incentives that for 50 years have caused the adoption of increasingly extreme laws and policies,” Cockburn said. OPP wants to back leaders whom the system has directly impacted, including those who’ve done time themselves. “That is our sense of how we can most cost-effectively engage in this field, with the highest rates of return on investment,” she said.

Where the Money’s Going?

So who does the Open Philanthropy Project actually support? Based on their assessment of the field, Cockburn and team have identified four priorities: local policy reform to reduce incarceration rates and advance public safety, prosecutorial reform, capacity building for reform advocates, and alternatives to incarceration.

One of the biggest overall recipients of OPP funding checks several of those boxes. Founded with initial support from Ford and the Public Welfare Foundation, the Alliance for Safety and Justice has become a leading national advocate for state and local reform. Since the alliance got up and running in 2016, OPP has furnished it with $11.75 million in general support, directing an additional $3 million toward its 501(c)(4) arm. OPP has also given $3 million to the Pew Charitable Trusts for its Public Safety Performance Project, and directed significant sums to the Live Free Campaign, a wide-ranging anti-violence organizing effort headed by Faith in Action, formerly the Pico National Network.

Over the past five years, OPP has also become a leading backer of prosecutorial reform. Cockburn sees efforts to change prosecutors’ practices as a compelling way to reduce the number of people in the system—an argument that finds support in Charged, a powerful new book by Emily Bazelon that documents the central role of unchecked prosecutors in driving mass incarceration. Grantees include Fair and Just Prosecution (a total of $3 million in general support), People’s Action (over $2 million for prosecutorial accountability), Color of Change, and a number of local grantees advancing prosecutorial reform in New York, Chicago, northern California, Oregon, and Colorado, including the ACLU.

Capacity building for reform advocates is another major theme. OPP has given over $3 million to the Justice Collaborative, $2 million to Color of Change, $1.3 million to the Texas Organizing Project, and $900,000 to the Essie Justice Group—all for general support. Although most of these grantees are politically progressive, OPP has also given general support to places like Just Liberty (just over $1 million) and the American Conservative Union Foundation (just over $600,000).

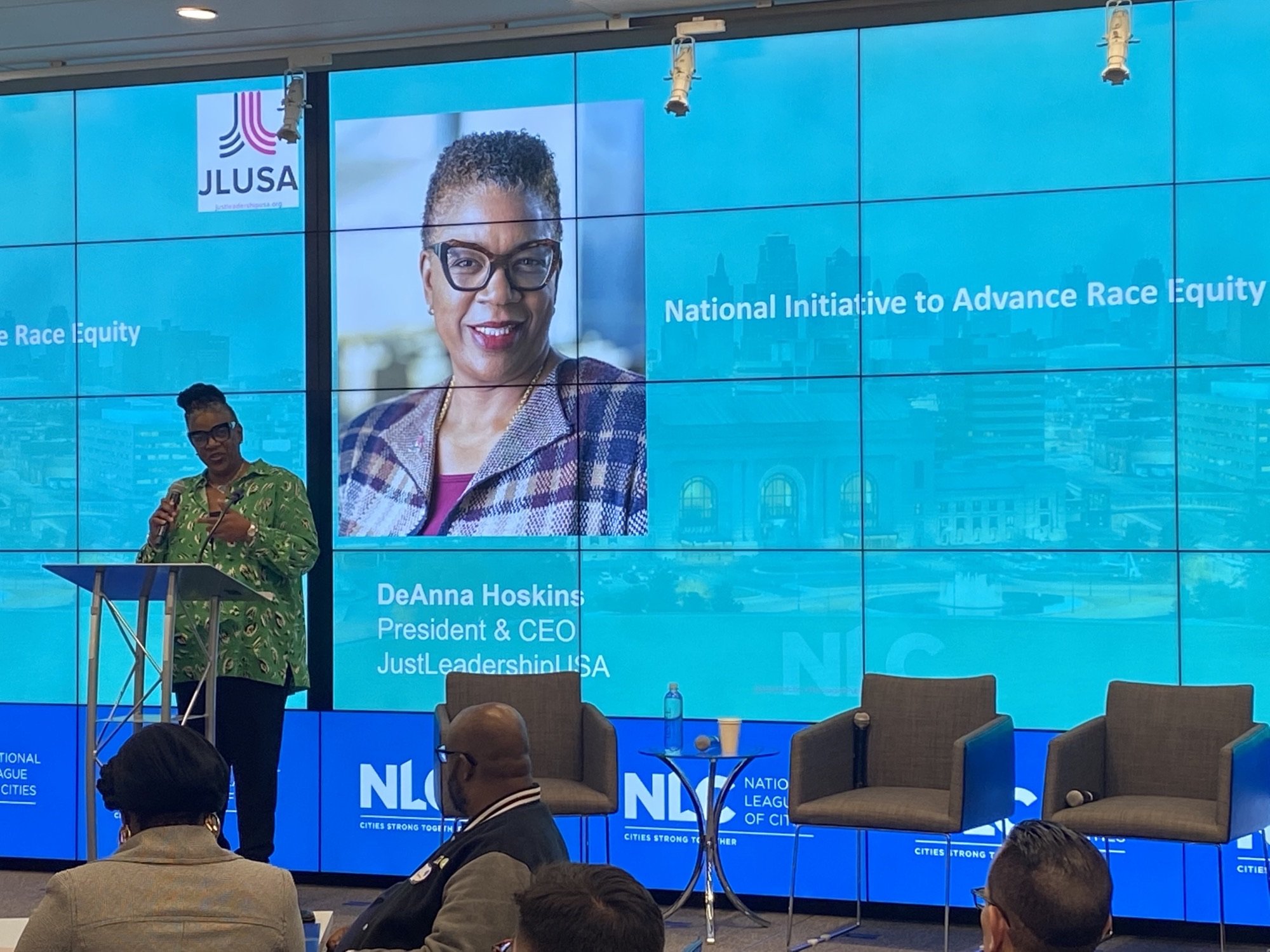

Finally, OPP’s portfolio includes support for initiatives that showcase alternatives to current incarceration practices. They include the Restorative Justice Project at Impact Justice and the Reform Jails and Community Reinvestment Initiative in Los Angeles. Through over $5 million in grants to JustLeadershipUSA, OPP has also been a backer of that organization’s campaign to close New York City’s Rikers Island Prison Complex, an effort that has gained a foothold, but remains mired in difficulties.

OPP is upbeat about the impact of its giving. Cockburn cites “national momentum” for change in prosecutorial elections in cities like Chicago, St. Louis, Boston and Philadelphia. She’s enthusiastic about bipartisan reform in Illinois, and “robust jail closure campaigns” in New York and Los Angeles.

To capitalize on the growing opportunities for progress, OPP often pulls multiple levers in its quest for impact. Although most of its giving so far has backed 501(c)(3) nonprofits, “we’ve heard from organizing groups that they are often taken seriously for the first time by local leaders when they begin to make use of 501(c)(4) resources,” Cockburn said.

OPP isn’t the splashiest criminal justice reform funder, avoiding the kind of big public rollouts of new initiatives that we’ve seen regularly in recent years from MacArthur and Arnold Ventures. But it’s quietly come to play a powerful role in this funding ecosystem, emerging as an indispensable ally of groups that previously never got funding at the level that OPP is now providing. In this sense, OPP’s criminal justice giving—which is backstopped by the Facebook fortune of Dustin Moskovitz and Cari Tuna—offers up yet another case study of deep-pocketed new philanthropists dramatically reshaping the funding landscape across many issue areas.