Seeking More Diverse Collections, an Arts Funder Looks Beyond Museums and Libraries

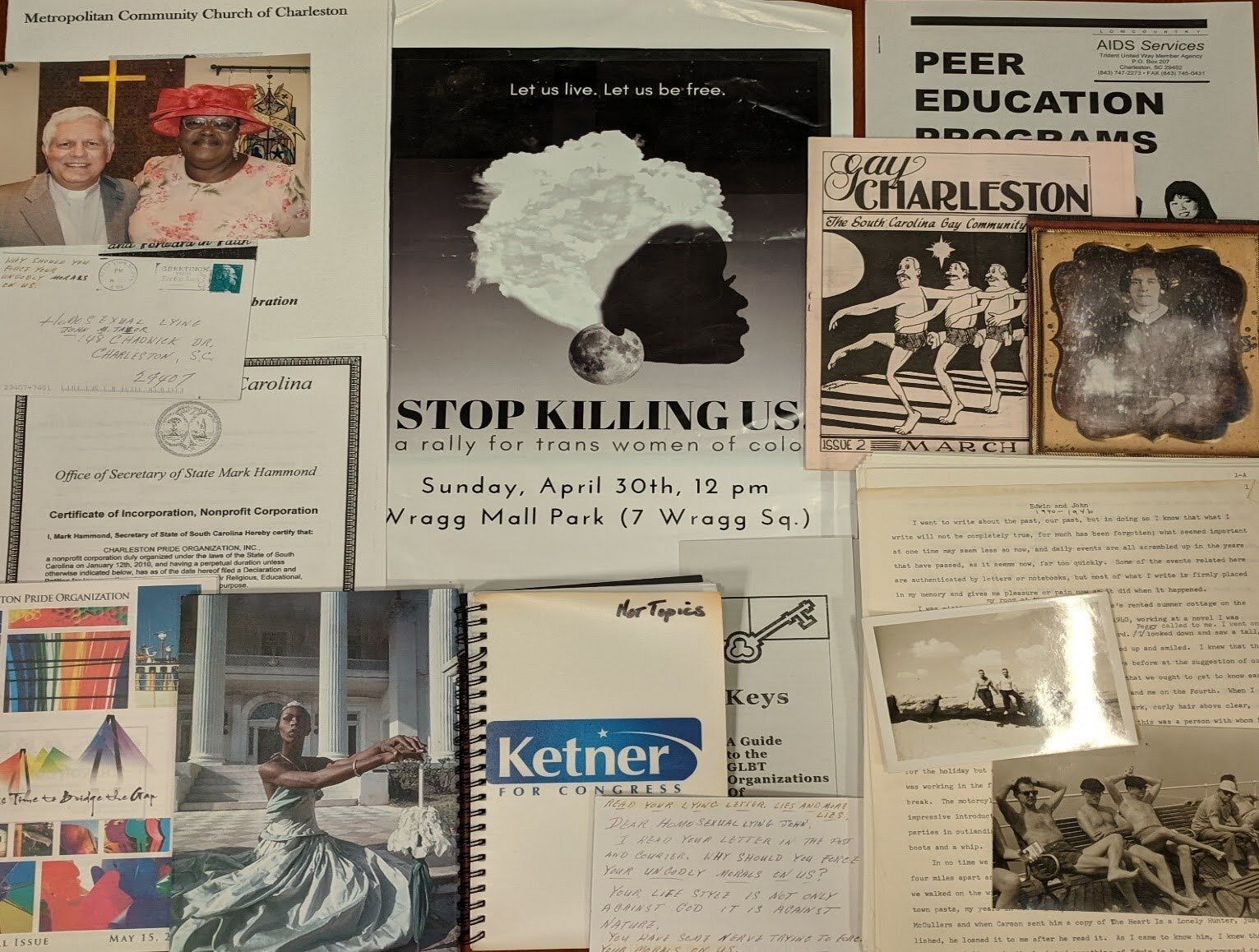

/Photos, letters, and other items from the College of Charleston’s Documenting LGBTQ Life in the Lowcountry Project, one of the only initiatives solely dedicated to preserving and documenting lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender histories in South Carolina.

One of the big themes across arts philanthropy is funders’ efforts to expand grantmaking and engage communities that traditionally weren’t on their radars.

This work can take many forms. Foundation leaders have rolled out participatory grantmaking panels, partnered with consultants, or even cold-called local BIPOC organizations after searching for them online.

Another promising strategy is emerging out of Chicago and South Carolina, where the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation looks to expand the definition of a collecting organization beyond museums and libraries to illuminate historically underrepresented groups and viewpoints.

Last September, the foundation announced “Broadening Narratives,” a $750,000 initiative for organizations whose collections “illustrate BIPOC communities, LGBTQ+ perspectives, working-class narratives and small community experiences.” The foundation is specifically interested in proposals that “bring forward new and recovered narratives” around Chicago’s history of immigration and migration, and South Carolina’s Lowcountry’s deeply rooted “experiences of race and power.”

The initiative is the result of a two-year process in which the foundation brought together experts and community members to solicit ideas on how best to reimagine a centuries-old art collection model.

“We have always supported museums and libraries,” foundation Executive Director David Farren told me, “but we understand that there are other organizations that serve multiple functions in a community, such as community centers, small culturally specific organizations, schools and churches that have important and substantial archives of a given community.”

These nontraditional organizations often housed archives from underrepresented groups because more “established” entities failed to value the narratives—consciously or otherwise—“based on race, gender, sexual identity, educational background, economic or social status, or because they are perceived to be unpopular, divisive or outside the conventional thinking of the day,” according to the foundation.

The new initiative aims to “expand the conversation about who keeps narratives and how they are valued,” Farren said, and “help these nontraditional collecting organizations better understand collecting practices and build their capacity to work with their archives.”

A collaborative process

The Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation awards grants to land conservation and arts programs in the metropolitan Chicago area and in southeastern South Carolina. It also provides general operating support for arts organizations to help build their capacity and audiences.

The foundation has supported all aspects of collections work, including processing, cataloging, digitizing and interpretation, since 2005. “All of these are core practices in the field,” Farren told me, “but because the span was so broad, it was challenging to understand how or if we were helping the field to address larger issues.” Leadership concluded it needed to put what Farren called a “strong frame” in place to give its collections strategy a clearer focus.

Normally, the foundation would keep this work in-house while reaching out to key advisors along the way. This time, however, the foundation took a different approach.

It convened advisory groups, grantees and board and staff members; hired two consulting groups, which engaged with a wider group of advisors to help in strategy development; and worked with community members to explore ideas about how it could positively impact the field. “It was a very collaborative process that took two years with many check-ins with our advisors along the way,” Farren said.

“This new strategy has tapped a need”

The five advisory groups that the foundation worked with were the Black Metropolis Research Consortium, Chicago Collections Consortium, Chicago Cultural Alliance, the College of Charleston’s Lowcountry Digital Library, and the Southeastern Museums Conference.

Farren described them as “our eyes and ears in the field,” which helped leadership “understand the challenges that are being faced by collecting organizations, from the small, community-based organization to mid-sized museums and libraries, to large institutions known around the world.”

The foundation’s work with these groups yielded two findings. First, increased capacity is a consistent need at organizations of all sizes; and second, the collections field needs to create better pathways for BIPOC professionals and pre-professionals to enter the field. Farren told me the foundation will look at ways to broaden the field through internships and fellowships in the coming years.

Fast-forward to late September 2020. “The launch of this ‘broadening narratives’ initiative arrives serendipitously as our country faces a historic moment of social justice reawakening and a compelling need for these trusted institutions to engage with the public on science-based realities, whether COVID-19 or climate change,” Farren said in the announcement.

The foundation held a virtual event for potential applicants in mid-October and the first application deadline is March 26, 2021. Farren told me the foundation has received “unprecedented inquiries” over the last two months about the initiative. “We’re having conversations with museums, libraries and collecting organizations of all sizes and from a breadth of disciplines,” he said. “It’s clear to us that this new strategy has tapped a need.”

Reimagining collections

At Inside Philanthropy, we’ve been covering several foundations’ attempts to broaden their reach beyond the usual grantmaking suspects. But what if prevailing models aren’t up to the task?

In a recent chat, Angie Kim, president and CEO of the Los Angeles-based Center for Cultural Innovation, talked about how funders’ work within the 501(c)(3)-based grantmaking model has failed to provide artists with durable and resilient support systems. “If the system is itself unequal and unfair,” Kim said, “then it’s necessary to try and get outside the conventional system altogether.”

The Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation’s “Broadening Narratives” initiative doesn’t appear to take a similarly paradigm-shattering approach. But it’s nonetheless predicated on the idea that many museums and libraries operating within the established system haven’t done a good job at capturing the perspectives of historically underrepresented populations.

These institutions were simply “not interested in these particular narratives,” Farren said, and their indifference created a “dominant cultural narrative” at the expense of diverse viewpoints. And so the initiative is going outside the conventional systems—e.g., museums and libraries—by focusing on smaller community organizations sitting on a wealth of powerful archival material. The foundation is accepting applications from 501(c)(3s) and fiscally sponsored groups.

The foundation identified other ways in which all types of collecting organizations can honor and amplify community voices. For instance, while preserving objects is at the heart of collections, existing practices often fail to provide a broader perspective and context. “Broadening Narratives” aims to make what Farren called “a shift from a narrow focus on material objects to widening the lens to include the narratives told by material objects.”

In a similar vein, highly trained professionals working at traditional institutions sometimes operate in a siloed environment without sufficient input from community members who have intimate knowledge of the objects in question. “We want to encourage and cultivate those conversations and sharing of information,” Farren said.

Lastly, the initiative is built on the idea that the best collection in the world is useless if the community doesn’t know it exists. “There are so many compelling, informative, heartbreaking and inspiring stories in collections that can benefit the broader community. The public should know these narratives and have a way to engage with them,” Farren said. “This has been a value of our collections’ strategy from the beginning, and we continue to find that we need to advocate for public engagement.”

Resolving museums’ “identity crisis”

While “Broadening Narratives” focuses on organizations operating outside of the conventional system, it also aims to democratize collections practices at museums that have been trying to shed their image as calcified “legacy institutions” primarily serving older and more affluent patrons.

Viewed through this lens, the foundation’s work speaks to a larger and more philosophical question posed by the New York Times’ Alex Marshall last summer: “What is a Museum?”

“Museums are having an identity crisis,” Marshall wrote in a piece exploring the International Council of Museum’s controversial efforts to revisit the body’s definition of a museum. The disagreements “reflect a wider split in the museum world about whether such institutions should be places that exhibit and research artifacts, or ones that actively engage with political and social issues.”

“Broadening Narratives” seems to seek a middle ground between these two paths by using artifacts to catalyze engagement around political and social issues pertaining to historically underrepresented communities in Chicago and South Carolina Lowcountry.

Farren further elaborated on museums’ evolving missions, telling me that “one of the challenges is that the historic model has been for museums to wait for the community to come to them.” Museums can no longer afford that luxury. The foundation’s strategy, he told me, looks at projects that “consider communities a resource and that think of ways to reach out to make connections with communities.”

Three months after the foundation launched “Broadening Narratives,” the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation announced that it issued $1.5 million to “community-based archive projects” focused on “preserving original source materials in all formats, including web-based content, with a focus on materials from historically underrepresented cultures and populations.” The foundation’s support exceeded the $1.2 million it awarded to its first cohort of 15 archives in 2019.

Mellon’s announcement suggests that this work will become increasingly important for equity-minded funders and museum leadership in the months and years ahead. Farren agrees.

“Particularly after this incredibly difficult time in our history, museums and libraries can serve as centers of re-connection, healing, re-imagination and thinking forward. But that important role doesn’t lie only with the objects within museums’ and libraries’ walls, but the ways in which these organizations participate with their communities as active neighbors.”