Downsizing's Upside: How Can Museums Capitalize As Boomers Dispose of Art?

/According to a recent piece in the New York Times, baby boomers want to downsize, and that means getting rid of many of their prized paintings.

That's good news for museums.

The mad dash to accumulate valuable contemporary art has been a recurring theme across the Inside Philanthropy visual arts vertical as of late. Another Times piece, this one from April 2016, sums up this trend:

Modern and contemporary art dominate the action these days—in auction houses and galleries, as well as museums. Everyone wants in, including a revered institution like the Met, which is striving to play catch-up even as it is struggling to pay the bills.

Of course, though, with contemporary art in short supply, getting "in" is easier said than done. And some bad things can happen as institutions rush to compete for such art in an age of scarcity. Indeed, the Met's inability to accumulate contemporary art—or more specifically, its arguably reckless spending spree to accumulate art—has been cited as one of the drivers behind Thomas P. Campbell's recent resignation as the institution's director and chief executive officer.

All of which brings me back to the boomers. Consider the data behind the imminent Great Boomer Sell-Off. According to the Times:

While only 4 to 5 percent of people over 60 move to a smaller dwelling in a given year, about a third of the over-60 population will move over a 10-year interval. And that number is expected to increase over the next decade as the rest of the baby boom cohort moves into prime retirement age—now a quintessential time for decluttering and giving things away.

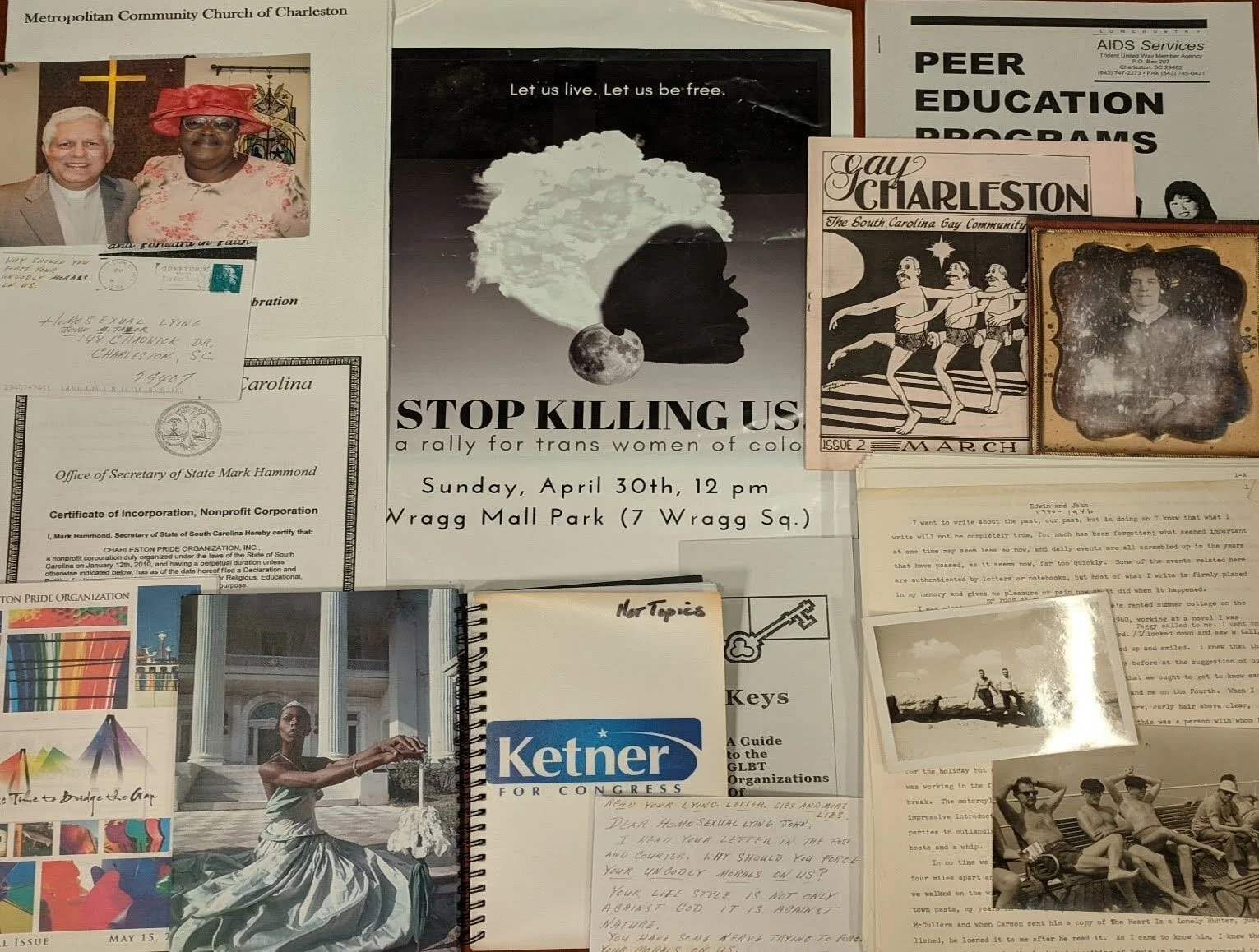

Art is among the stuff that people tend to give away when they downsize, and it's likely no coincidence that we've lately been seeing a steady stream of significant donations of artwork to museums and universities.

If this demographic surge in art gifts is real, that's exciting stuff. But it raises a critical question: How, exactly, can museums capitalize on this trend?

First off, relationships matter. This sounds trite, but it's true and worth repeating as a mantra. Read any Inside Philanthropy piece on a contemporary arts give, and nine times out of 10, you'll find it was the culmination of a long-term relationship. Many times, the donor in question sits on the museum board. Sometimes the donation is brokered by a friendly go-between. Either way, the seeds were planted years—and sometimes decades—in advance.

Secondly, just because a collector's work is sitting in his or her basement doesn't mean they want the donated work to meet the same fate. One of the messy byproducts of the contemporary art rush is that museums adhere to a "buy first, ask questions later" approach. They may not have the space to display all the work, but hey, these are details that can be ironed out in the indeterminate future.

This approach doesn't sit well with many collectors. In fact, it was one of the factors behind J. Tomilson Hill's decision to start his own gallery. At least he knows people will see the stuff. In fact, the problem is acute enough to warrant the attention of funders. Case in point: the Henry Luce Foundation's American Art Program, which focuses on "reinstallations, or the act of either renovating a space or physically relocating an existing collection" to help museums get the most bang for the curatorial buck.

The bottom line here? Institutions need to assure would-be donors that their work will see the light of day and be treated with care it deserves. As one donor in the Times piece noted, "Conservation is terribly important. And it’s out of respect for the artists. I would hope they would think that I was being responsible."

Regional art museums, with smaller collections, are starting to enjoy a growing advantage in competing for collection gifts. With the storage facilities at places like MoMA and LACMA stuffed to the gills, local players have a chance to make a strong pitch to donors: Your art will not only be seen, it will help take our institution—and city—to a whole level.

Lastly, museums should think long-term. Many of the pieces they come across may not have immediate financial value, but that, of course, can change. According to art historian Karl E. Willers, the flood of works that may be coming to institutions around the country in the next decade could "broaden the definition of postmodern art." That's an exciting—and potentially quite lucrative—speculation.

And so the pool of nearly 80 million baby boomers and their art collections represent an intriguing opportunity for museums. The boomers' crates of old Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young records? Not so much.