What's Happening with Arts Philanthropy Right Now? An Innovative Funder Takes Stock

/sirtravelalot/Shutterstock

The Boston-based VIA Art Fund recently awarded grants totaling $310,000 during the first half of 2017 for contemporary visual arts projects, directly supporting over 50 artists, writers and curators, and nine visual arts organizations and platforms.

Given concern about President Trump’s plans to reduce public arts funding, coupled with the relative scarcity of direct funding to artists, the fund's announcement underscores the growing influence of institutional arts funders in fields lacking individual and public support.

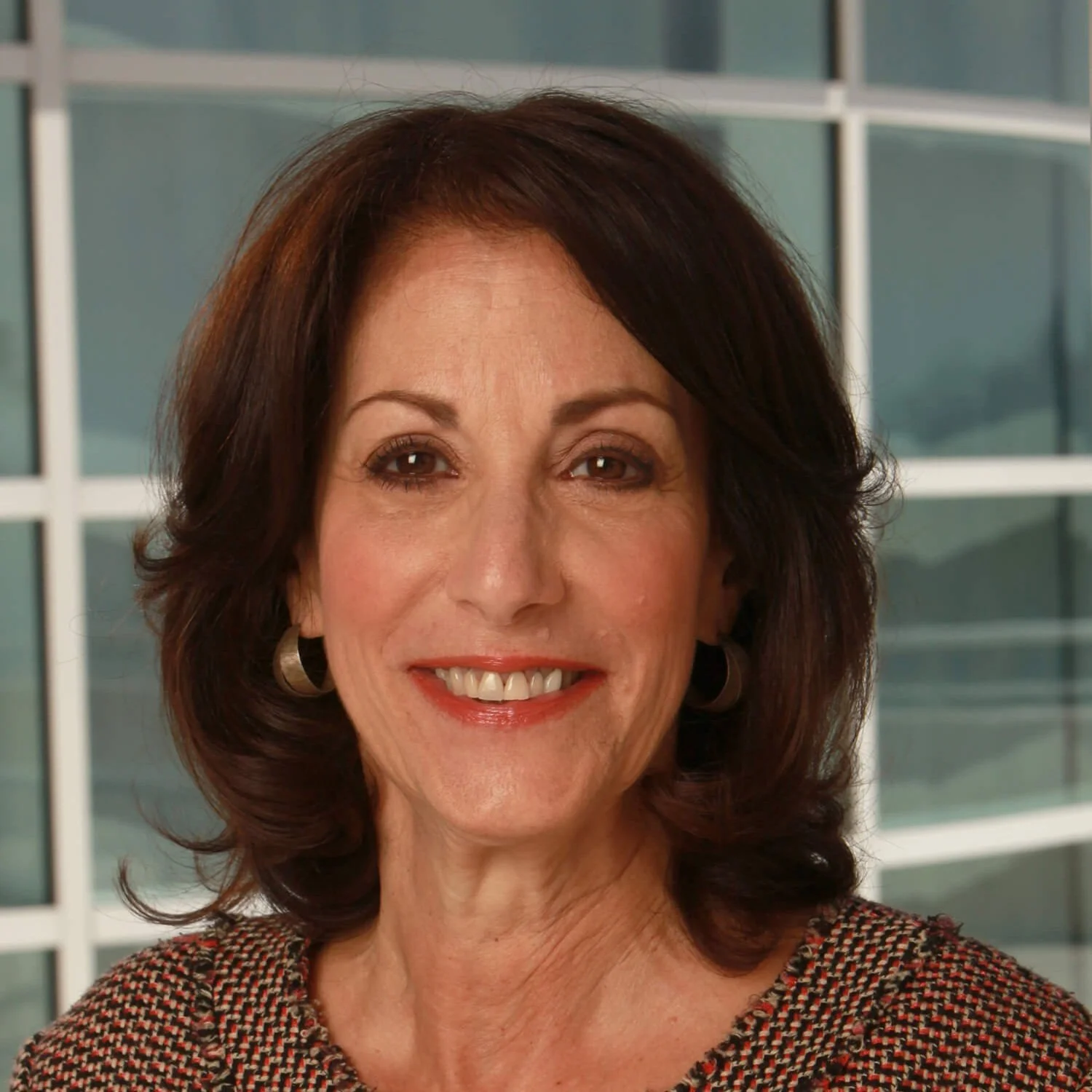

Commenting on the announcement, VIA President Bridgitt Evans said, "We are thrilled to fund over $300,000 in grants to support new work by groundbreaking artists and independent organizations for projects that may not otherwise have come to fruition given the current state of public funding for the arts."

I recently had the opportunity to connect with Evans about the precarious state of federal funding for the arts, as well as other timely trends permeating the arts philanthropy space. Here's a recap of our discussion.

The Road to Arts Philanthropy

Evans has a background in finance and real estate development, and spent nearly 20 years structuring acquisitions and development deals. In the early 2000s, she started collecting works by artists like Glenn Ligon, Christopher Wool, R. H. Quaytman, Mark Bradford and others.

"For me, the most rewarding aspect of being a collector was the opportunity to engage with compelling artists of my generation, and to be exposed and challenged by their ideas and visions. As a collector and, later, a museum trustee, I greatly enjoyed studio visits and hearing from the artists about the production of new works and upcoming exhibitions.

"At the same time, I also realized this kind of encounter was something few individuals had access to. Direct engagement (or insider’s view, if you will), historically, was reserved for top museum trustees and patrons who make significant contributions in support of large collecting and exhibiting institutions."

Evans channeled her professional experience and work in the museum world into the creation of VIA. "The same way that in the finance or real estate sectors you see different investors partnering to make a large acquisition or to fund a start-up business, VIA was conceived as a vehicle to pool resources from multiple individuals and smaller family foundations to accomplish philanthropic activities and diversity that might not be possible for a single individual/entity."

A "Mutual Fund for Philanthropy"

A recent Inside Philanthropy piece echoes Evans' thoughts about the idea of the patron as an "angel investor." Such patrons "see that something has potential to grow, and you want to support that incubation period,” said Rose Lee Goldberg, an art historian at New York University and founder, director, and curator of Performa, a leading organization dedicated to performance art.

We take this relationship for granted, but that wasn't the case in 2013, when Evans started VIA. "I felt there was a lack of philanthropic tools to harness the growing public interest in art and culture beyond the traditional institutional efforts to attract the very high end of the donor pool in support of civic cultural institutions."

VIA was born as a "'mutual fund for philanthropy' to achieve similar goals as the largest family foundations and funds, but at a lower entry cost," she says. Each partner donates a minimum of $10,000 and its Grant Advisory Committee members donate at $25,000. Grants range anywhere from $15,000 to $100,000.

Why So Little Direct Support For Artists?

VIA is an outlier in the arts philanthropy space in that it provides direct support for artists. It's a counterintuitive phenomenon because, as Evans notes, "more artists and projects and platforms should mean more opportunities for attracting capital, not less." So why the disconnect?

"I think it is more about a lack of social philanthropic entrepreneurs and vehicles in the arts philanthropy space, platforms that can harness the philanthropic potential of the sector. And in the more narrow subcategory of art in the public realm (which is important for VIA), a lack of public exhibition producers."

What about the theory that donors like to have control over how funding is allocated? Evans argues that the issue isn't control as much as it is defining "outcomes and impact." She says, "Rather than write grants for the benefit of individual artistic practice, the donor asks 'What is the outcome of this grant? What is the work of art? Where will it be exhibited? Who will enjoy or benefit from that?'"

Evans suggests donors would be more amenable to direct support if presented with a more transparent and outcome-based grantmaking process.

Additional IRS reporting requirements make direct support even more time-consuming and complex. "It is not something that most private or small family foundations are used to dealing with, particularly those without in-house staff dedicated to the arts sector."

This reality underscores a Catch-22. Donors want to generate maximum impact, yet by outsourcing grantmaking, they're distancing themselves from the very artists they want to support. VIA provides direct grantmaking precisely because it maximizes its ability to generate optimal outcomes. "We highly value granting directly to artists as that is our best opportunity for direct engagement, understanding and agency," she said.

Gauging the Impact of Funding Cuts

I next asked Evans about donor giving in the face of ongoing and further cuts to public funding.

"In general, there is not enough transparency in the operations of arts organizations for the average donor to 'feel' the loss of the NEA," she said. "People and organizations will do what they always do, and that is to double down on fundraising, appealing to their most trusted supporters, and adjust their program to meet their revenues.

"But on the margin, and in the areas where funding for the arts is probably most vulnerable, there will be fallout. The artist in small-town, middle America, whose only hope of getting their local musical or art exhibition funded—one whose ambition perhaps outstrips their current level of funding—was the NEA, will be forced to let go of their dreams and ideas."

On the other hand, Evans sees reasons to be optimistic. First, she cites the potential in "engagement with works of art, particularly in the public realm." Second, she envisions more support for socially conscious donors who "increasingly see the arts as a way to invest in advancing their goals and will increase their philanthropy."

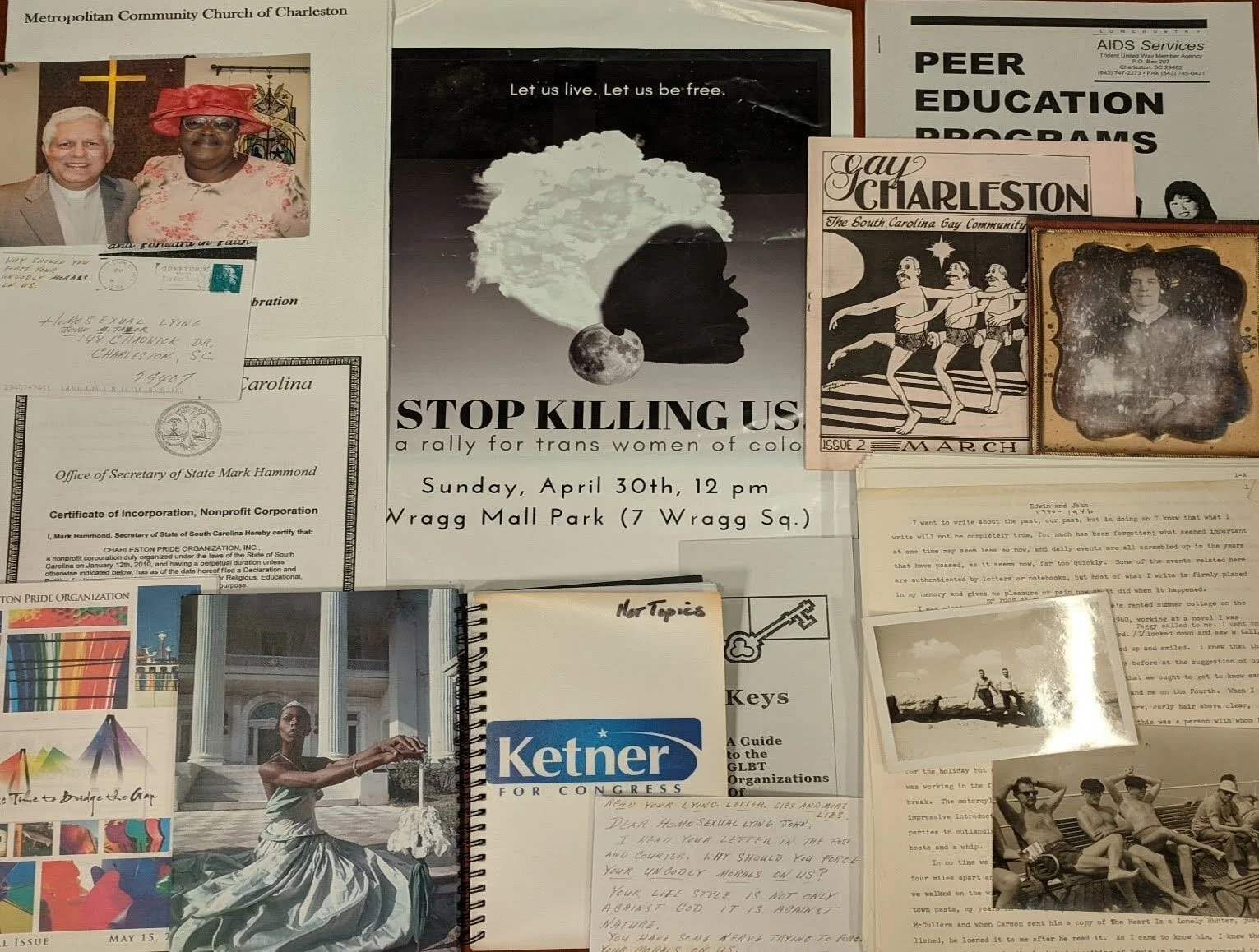

Evans noted that artists have "always been at the forefront of/responded to political conflicts, from Picasso’s Guernica to the artists’ responses to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. And while the role of collectors is often under the radar, there was always someone underwriting those works."

VIA is "not simply supporting an artist practice, we are looking for an outcome and its impact on society," she said. "How many people will visit the exhibition? What will be written about the project/exhibition and the ideas behind the work? What information will be available on-line for broad dissemination for those who cannot see the work?"

Given the current political climate, Evans said VIA’s "support for socially engaged works will only increase."

An Arts Ecosystem in Transition

Given this drift toward greater engagement and socially conscious art, Evans wonders if the ecosystem has the infrastructure or awareness-raising acumen to respond appropriately.

"I would posit that the industry has not offered a full complement of philanthropic ideas and funding vehicles to infuse the public with the ideas and impact of art in order to galvanize public understanding and funding. You still need social entrepreneurs and ecosystem platforms and public awareness."

Recent coverage corroborates Evans' thesis.

Slowly but surely, foundations have pivoted to create funding vehicles to drive engagement across diverse communities while some are "edging politely but firmly away" from legacy institutions that cannot "demonstrate a significant contribution to solving or soothing specific social or economic traumas." Others are boosting transparency across the grantmaking lifecycle.

At the same time, outfits like Upstart Co-Lab are creating "opportunities for artist innovators to deliver social impact at scale." Click here for takeaways from my chat with Upstart founder Laura Callanan.

Support for Organizations and Artists "On the Margin"

Earlier, Evans posited that organizations and artists "on the margin" would be disproportionately affected by NEA cuts. A report entitled "Diversity in the Arts" by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management echoes this sentiment. "When grant funding is slashed, the organizations that suffer most are the smaller groups, which have lower levels of visibility among other donors," its authors noted.

Therefore, another big question moving forward is whether funders are operationally equipped and financially willing to assist organizations, professionals, and artists at the margin.

This thinking goes to the heart of VIA's Incubator grant category, created to support small-to mid-size nonprofit organizations that embrace innovation and experimentation. According to Evans, the program came about because "we saw that smaller nonprofit alternative spaces or discursive platforms that are so important to nurturing emerging artists or new ideas, or more broadly serving a different sector of the public, were not as supported by individuals and foundations as the larger institutions.

"Part of this is an issue of scale. The smaller nonprofits, which might consist of a handful of individuals, cannot afford significant, dedicated fundraising staff, so it falls to the founders/directors to fundraise for the organization. And in many cases, it is harder for the private funder to understand and relate to their work. It may be more academic in nature, or more innovative and emerging in presentation. Thus, we designed a grant category to meet their needs."

Unlike its Artistic Production Grants, which fund a particular artist and work of art with a clear exhibition strategy/plan, VIA's Incubator Grants are for general operating support. Incubator grants totaling $45,000 were awarded to support the New York-based organizations Independent Curators International, Triple Canopy and New Orleans-based Antenna during this most recent funding cycle.

VIA also created the $15,000 Curatorial Fellowship Grant after it uncovered a lack of funding for independent travel for mid-career curators.

"We learned that tight budgets, no matter what size the institution, disproportionately affect resources for curatorial research and travel for mid-career curators, just at a time when they have the experience and maturity in their own curatorial practice to really benefit from such an investment," Evans said. Last year, VIA named its inaugural fellow, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago curator Naomi Beckwith.

Tapping Collector Enthusiasm

A few weeks before my chat with Evans, the Ford Foundation announced the creation of its Art for Justice Fund to promote criminal justice reform. Seed money came from philanthropist Agnes Gund with a $100 million donation from the sale of artwork from her personal collection.

A collector herself, Evans considers this a perfectly logical development. Collectors are "exposed to a wider variety of artists, practices, ideas, and social commentary," and moving forward, collectors like Gund will "direct the same passion they have to collecting to philanthropy."

But again, let's not put the cart before the horse. "The arts philanthropic sector," Evans says, "needs to provide a way to tap into the passion that collectors apply to acquiring a work of art to supporting artists and their artistic practices. That is where VIA, and many other organizations and platforms, will have to step in and help create the vehicle to harness that passion."

One way VIA does this is by having donors take part in the grant selection process. "From reading proposals to deliberating and creating dialogue about them to selecting and awarding the projects, our partners feel like they are encouraged to take a more active role."

Creating Meaningful, Accessible, and Diffused Arts Experiences

Looking ahead, Evans cites three interrelated challenges facing the arts philanthropy space.

First, the need to shift public opinion and to increase support for the arts, especially given recent political developments. "I am not just talking about attracting philanthropists and communicating the value or impact. I am thinking on a more grass-roots level. Culture is under attack, it is seen as a privilege of coastal elites, not as a shared value and priority as a nation."

Second, the need for institutions both large and small to "remain relevant without succumbing to market forces, and to appeal to broader audiences without falling into the trap of continuous expansions, blockbuster exhibitions or becoming tourist attractions.

"It is difficult to balance the need to appeal to new and expanded audiences without becoming mere forms of entertainment and turning art works into Instagram material. As the current political climate shows, it is more and more difficult to find a middle ground between populism and museums’ perceived elitism."

This challenge is particularly acute for smaller institutions and informs the logic behind VIA's Incubator Grants.

Lastly, "We need more non-traditional cultural organizations, smaller exhibition venues, public art producers, local residency programs, and other cultural providers in order to diversify away from a heavy concentration of thought leadership and philanthropic capital in just a few cities. This, in turn, would positively affect the shared national values and accompanying grass roots support and funding."

An Ecosystem that Complements, Rather than Competes

The existing arts ecosystem is a patchwork design composed of public and private funders. The former category was never particularly robust to begin with, and with cuts looming, its future is uncertain. The latter, whose funding model typically leans on high-end donors, rewards "continuous expansions" and "blockbuster exhibitions" at the expense of individual artists, smaller organizations, and those situated far from large urban centers.

Throw in the need for greater public engagement, the "artist as activist" boom, and the expanding influence of social entrepreneurs and collectors, and it becomes apparent that the current ecosystem needs support. This is where VIA Art Fund comes in.

Evans doesn't envision VIA replacing the NEA or stealing the thunder of larger institutional funders. Rather, "one of my goals in founding VIA was to connect with other like-minded art enthusiasts from across the country and to build an ecosystem to complement the currently dominant geographic and institutionally-centric system."

Citing the education space as a replicable model for the arts world moving forward, Evans acknowledges that there is much work to be done in terms of what she called an "industry build-out."

"I think we are just at the beginning," she says.