It's One of the Biggest Bets in Arts Philanthropy Ever. What's the Verdict?

/When Alice Walton's Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened its doors in 2011 in Bentonville, Arkansas, activists asked why heirs to the Walmart fortune would spend billions on a museum as the retail chain cut worker benefits. Art critics lamented its "curatorial missteps." Jeffrey Goldberg, a correspondent for the Atlantic, called it a "moral tragedy."

It seemed that Crystal Bridges, inconveniently located in a "flyover" state, might well become a new textbook case of nouveau philanthropy gone wrong—a reminder that lots of money doesn't necessarily buy either good taste or good judgment. Even its name sounded hopelessly middlebrow.

The museum recently celebrated its five-year anniversary. Since its opening, it has welcomed over 2.7 million visitors. It has promoted American art on the world stage and rolled out new education programs.

Is all that criticism now water under the bridge? (Sorry, I couldn't resist.)

I can't say definitively, but a lot of the ire seems to have softened. It may just be conjecture on my part, but the activists who initially scoffed at the museum now have more pressing concerns to attend to.

In addition, success has a way of tamping down dissent. The museum has quickly grown into an international arts powerhouse, and its founder seems to have big plans moving forward. Why is this is important? Simple. Alice Walton happens to be "America's Most Important Arts Philanthropist." She has a multi-billion-dollar fortune, and now, a track record for executing an ambitious vision. We've been musing for over three years about what lies ahead for Walton—and how Crystal Bridges might operate as the platform for a larger philanthropic arts agenda.

So Crystal Bridges' press release commemorating its anniversary is worth the read. It ticks off its most memorable successes thus far, and more importantly, sketches out its vision for the future. Let's start with its accomplishments.

Attendance exceeded expectations, with more than 650,000 visitors in the first year and 500,000 to 600,000 in subsequent years. Twenty percent of visitors came from abroad or non-"touch states," refuting the naysayers who argued that tourists would bypass Bentonville. Fifty-five percent of visitors hailed from Arkansas.

“I knew this museum was needed," Walton said. "I grew up here and didn’t have access to art, and I knew we wanted to change that. What I underestimated was how much people wanted to have access to that great art."

Since the museum’s founding, the number of objects in the collection has grown from 1,555 to more than 2,400, including works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Benjamin West and Joan Mitchell.

This may not satisfy critics like Jeffrey Goldberg, but it underscores a point best articulated by Forbes' Abigail R. Esman. She writes, "Some of these purchases, costing tens of millions of dollars, hang, not in private homes for the selfish enjoyment of the Walton family, but on public walls for the education and enrichment of the American people."

Crystal Bridges has also positioned itself as an international emissary for American art. Its American Encounters collaboration with the Louvre, Atlanta's High Museum of Art, and the Terra Foundation for American Art aims to broaden the "appreciation for and dialogue about American art both within the U.S. and abroad."

Walton cites access as the central focus for Crystal Bridges, which offers free admission and a "welcoming" visitor experience:

It goes back to the root of museums. In Europe, when they first developed, museums were thought of as a place for the elite and the upper class. That tradition carried over into most of the first museums in this country. And it is still present—in the architecture, the grandeur, and the design of those original buildings—they are still kind of intimidating to most people. I knew that we wanted a place that did not have that intimidating feel.

So what are some priorities moving forward? First, the press release cites the redevelopment of a decommissioned Kraft Foods plant located 1.5 miles south of Crystal Bridges into a "vibrant facility for visual and performing arts." I found this venue, which is slated to open in 2019, to be particularly interesting, because it targets that elusive and coveted demographic, the millennials.

Indeed, the Crystal Bridges' success, coupled with the acquisition of the Kraft plant, partly explains why the Walton Family Foundation's 2020 plan does not include money for a large-scale performing arts center in Bentonville.

Secondly, the museum is ramping up its education initiatives. Back in 2014, researchers conducted a large-scale, random-assignment study of school tours to Crystal Bridges and concluded that "strong causal relationships do, in fact, exist between arts education and a range of desirable outcomes."

The study led to the creation of the Distance Learning Project, which offers free, online art-related courses for high school students. It also informed a $15 million grant from the Windgate Charitable Foundation to support "an ongoing process that identifies current issues facing schools and develops responsive arts-based initiatives to improve student outcomes."

The Windgate grant speaks to the museum's third priority moving forward.

After the Walton Family Foundation founded the museum in 2005, it began the application process to convert Crystal Bridges from a private operating foundation to a public charity. "After a five-year assessment," the press release stated, "the museum has received official notification of its public charity status."

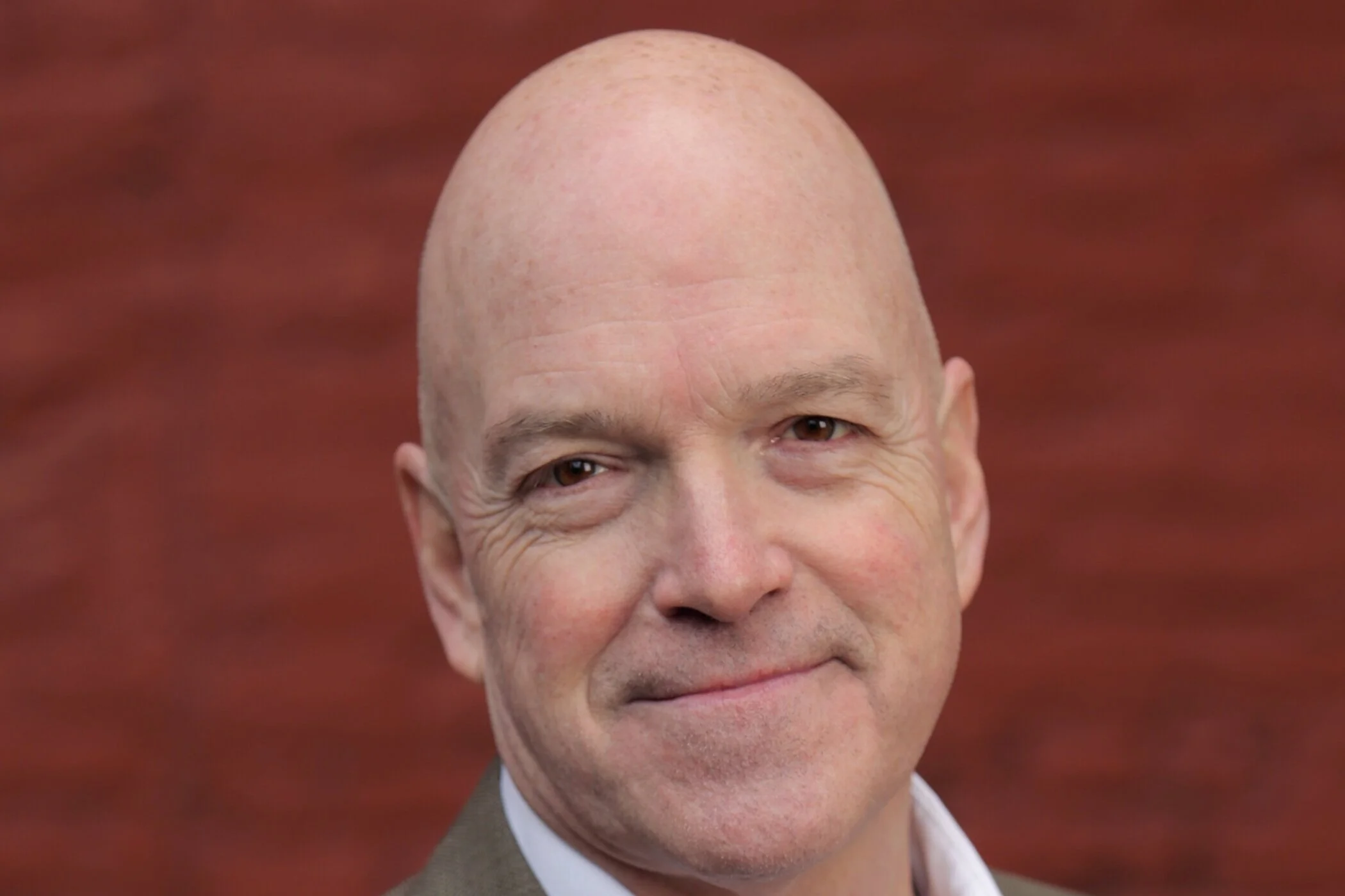

According to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art Executive Director and Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer Rod Bigelow, "the public charity status ensures we will continue to have a variety of funding sources and opens up even more possibilities for grants and support that will help broaden the reach of Crystal Bridges’ educational programs."

It's also worth recalling a prediction made by Inside Philanthropy's David Callahan back in 2014. Callahan argued that Crystal Bridges would eventually become far more than a museum, but also a grantmaking foundation itself. (Similar to the well-endowed J. Paul Getty Trust, which morphed into a far-ranging "cultural and philanthropic institution," even as it remained best known for its two museums in Los Angeles.)

Hints of its grantmaking future could be seen last year when the museum created the Don Tyson Prize for outstanding achievement in American art. Its inaugural recipient was the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art.

Bottom line, here? Just as Sam Walton developed a strong brand for his retail chain—think "low prices" or "easy shopping"—his daughter is doing the same with Crystal Bridges. In five short years, her museum has become synonymous with access, education and American art. And she may be just getting warmed up.