Fire Sale: A Museum Plans to Auction Off Prized Works. How Will Donors Respond?

/Credit: studiostoks/shutterstock

News out of Massachusetts points to two salient questions in a cutthroat visual art space where museums struggle to stay afloat.

First, when is it OK for a museum to sell its holdings to shore up its finances or fund renovations? And second, will donors approve of such a strategy? In the past, we've looked at the narrow legal issue of selling artwork that was given with the expectation that it would be a permanent part of a museum's collection. As with other kinds of gifts, such as endowed chairs at universities, original donor intent can impose major constraints on how nonprofit institutions handle art work.

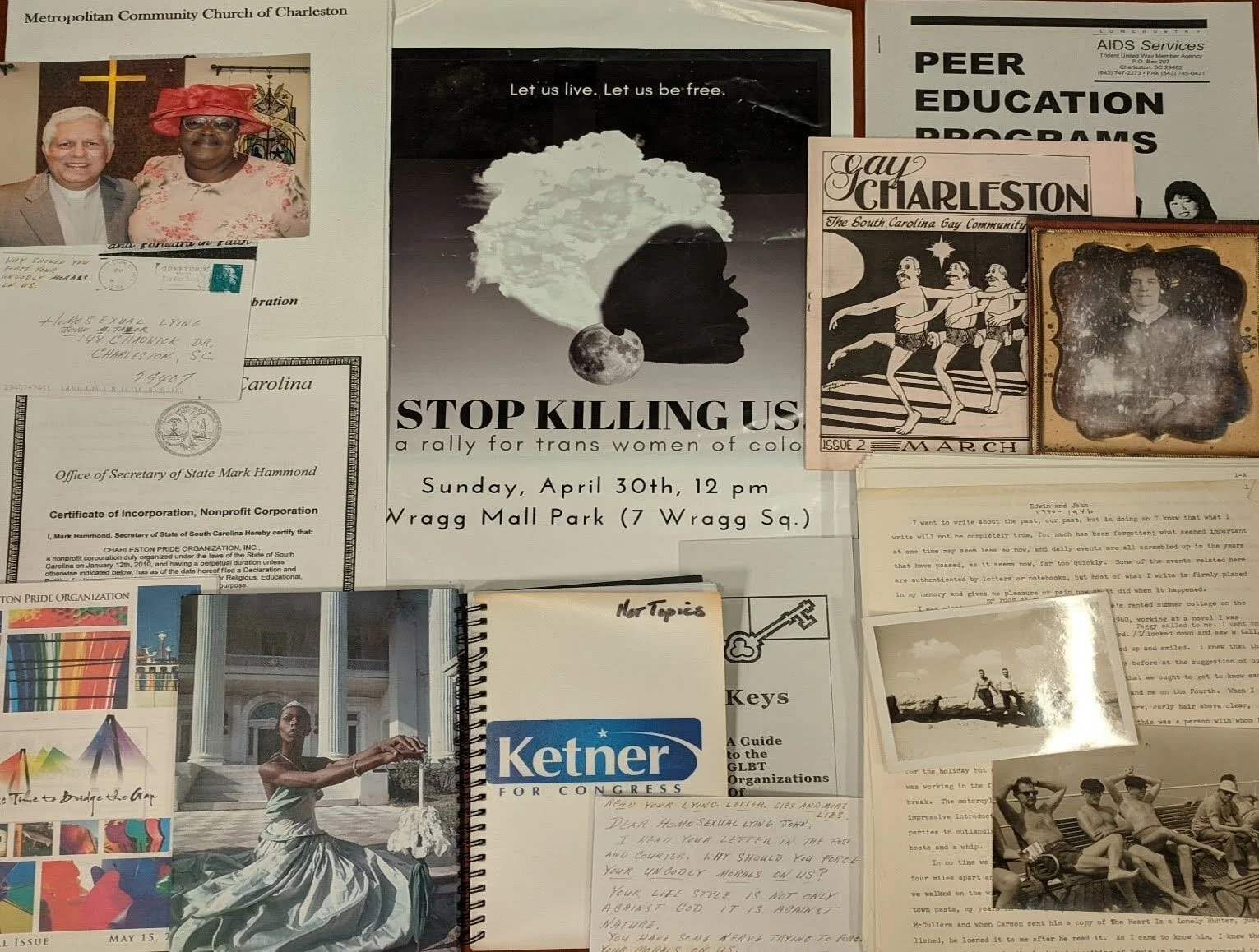

But for broader insights on this issue, let us now consider the saga of the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

It all started innocuously enough.

In July, the museum announced a "reinvention plan" to refocus its mission away from fine art to science and history. The plan called for $20 million to expand and renovate the museum, and another $40 million towards an endowment.

Is the plan audacious? Yes. Risky? Unprecedented? Not in the slightest. Time and time again, museums have turned to bold capital projects as a means to engage donors. It's standard operating procedure.

There was just one catch. The museum said it would sell 40 objects and paintings from its collection to raise the necessary funds. The collection included two Norman Rockwell works that were deemed "no longer essential" to the museum’s programming. The 40 objects were expected to sell for $50 million.

To say the strategy, known as "deaccession," generated pushback would be an understatement.

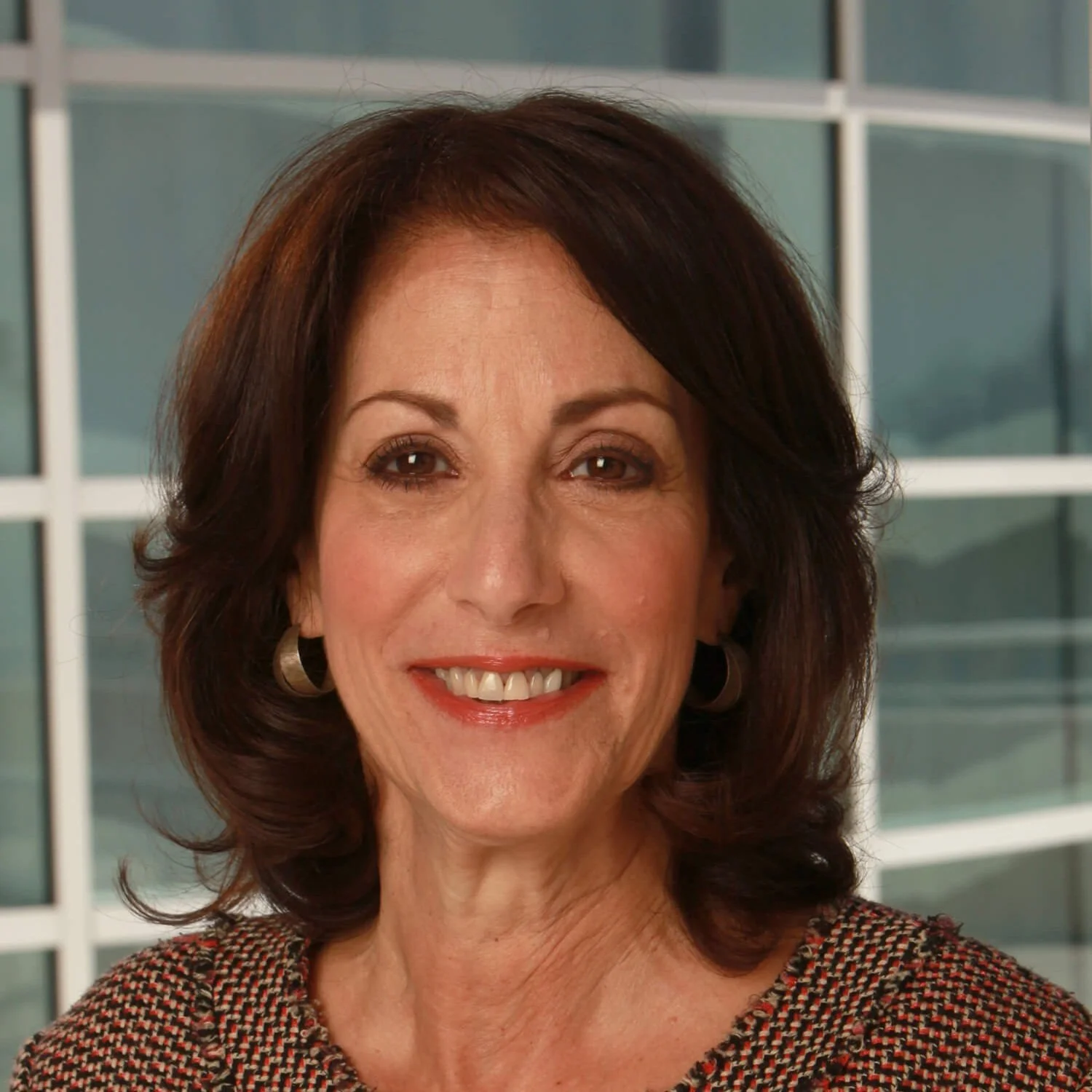

Laurie Norton Moffatt, director of the Norman Rockwell Museum, asked the museum to reconsider the sale. More than 20 local artists and educators formed "Save the Art at the Berkshire Museum of Natural History and Art" and called on the museum to stop the bid.

And the American Alliance of Museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors issued a joint statement opposing the plan, arguing that by using proceeds from the sale of collections for something other than acquisition or direct care of collections, the museum broke its code of ethics. Berkshire Museum Executive Director Van Shields held firm, arguing that without a change in finances, the museum would be out of money in less than eight years.

Then things got really interesting.

An anonymous group of donors offered the museum $1 million to pause the planned sale for at least a year. The dollar amount wasn't particularly striking, but the message from at least one corner of the donor community was unmistakable: Let's all take a deep breath and think this over.

The donors, according to the Art Newspaper, hoped that a year’s delay would allow them to assemble an outside panel to "look at the institution’s financial situation and come up with a solution that would allow the art to remain at the museum." The museum refused.

"Although we must decline, we are grateful for the offer," Elizabeth McGraw, the president of the museum’s board of trustees, said in a statement. "Some individuals are frustrated because they think that a pause in the sale would lead to a different financial path, somehow changing this harsh reality," McGraw wrote. "However, the consequence of a delay with the auction could be that the museum may close even sooner."

Needless to say, there are a lot of "consequences" floating around right now, most notably, the extent to which donors will ultimately support deaccession as a viable (or tolerable) strategy—at Berkshire or anywhere else, for that matter.

As always, context is critical. Berkshire was operating a crowded market, competing with other regional art powerhouses like the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute and the Norman Rockwell Museum. Its pivot toward science and history could be viewed as a prescient and differentiating strategic decision.

"Competing against other major art institutions, that is not our niche," said Elizabeth "Buzz" McGraw, president of Berkshire Museum's board of trustees. Why should Berkshire continue to double down on what she called a "failed model?"

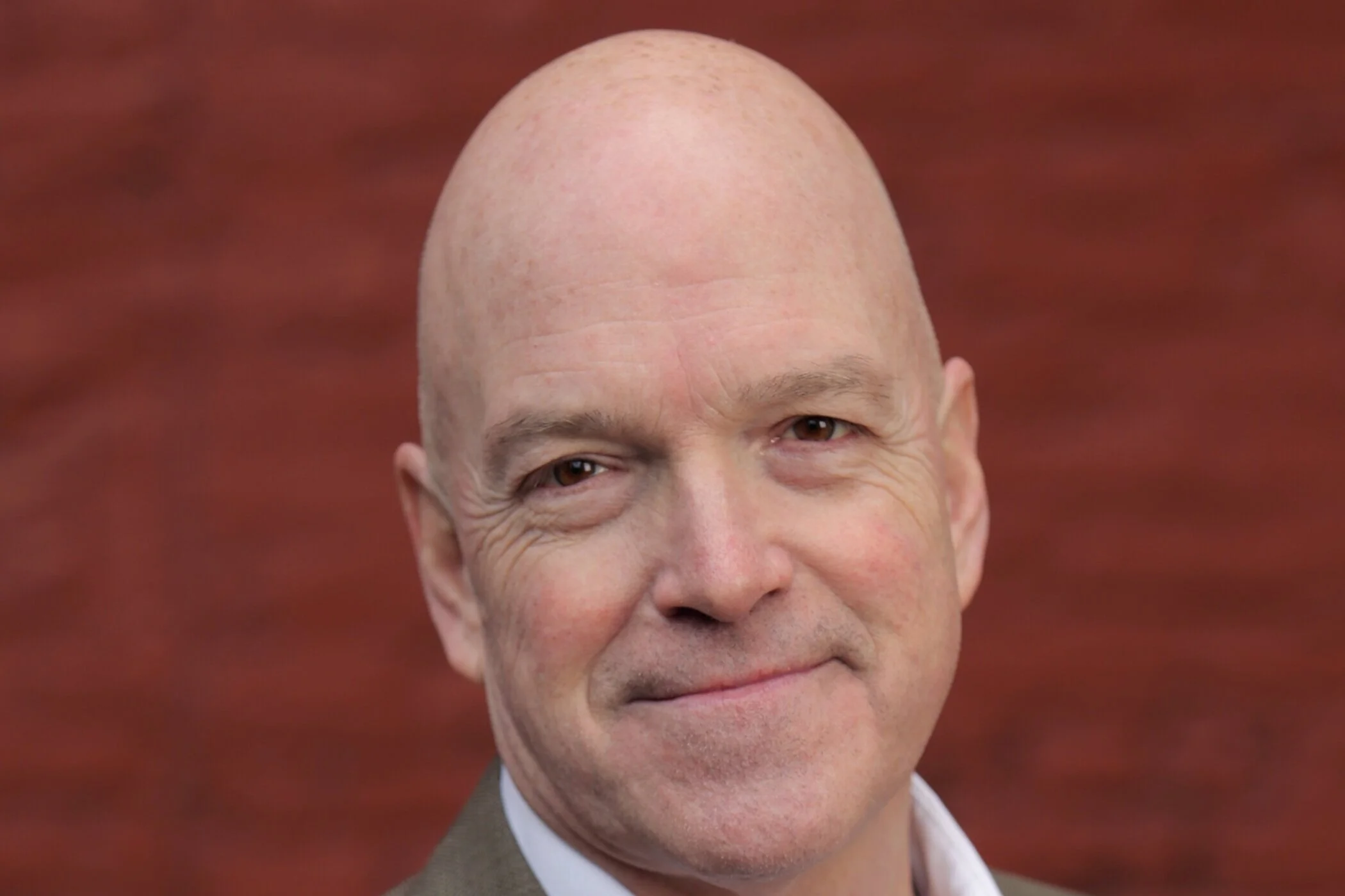

Some of the museum's most vocal support came from representatives from other museums. "They're sitting over there around all that art," said William "Mac" Sudduth, director of the Schenectady Museum. "It probably makes really good sense to focus their mission down."

The fact that Berkshire's plan makes "really good sense" may have a ripple effect beyond Massachusetts. Will Berkshire inspire other museums to follow a similar path?

Its change of mission notwithstanding, the museum lacked a deep-pocketed funding base that might have helped it build an endowment to address its ongoing structural deficit. Lacking such an infrastructure, the museum turned to selling valuable art, the fundraising equivalent of low-hanging fruit. Museums in a similar predicament may be tempted by this strategy—even if it's low-hanging forbidden fruit.

Which brings me to the X factor in this complex equation: Donors. Will they play ball if a museum takes the deaccession route? Consider the philosophical, financial, curatorial and PR-related factors at play.

To the former, the Rockwell Museum's Moffatt argued that "selling these treasured assets actually poses a debilitating economic ripple effect beyond the museum, not to mention would be a profound spiritual loss to the community." Deaccession, in other words, may turn off donors who, by their very nature, value stability. What's more, many aren't particularly keen on the capital project gold rush, regardless of where the funding comes from.

And so they may close their checkbooks and say, "This isn't what I signed up for." Indeed, the fact that anonymous donors banded together to pause the auction underscores their disapproval of the museum's plan.

Also remember that donors, increasingly beholden to the ROI mindset, demand operational excellence. They want museums to establish a broad and deep funding base. They don't want to carry the burden alone. And when a museum fails to do the legwork and instead sells valuable art, donors may feel as if they're taking the easy way out. "To think that selling the art will save the future is simply to push the challenge down the road while diminishing the strength of the institution," said Moffatt.

Association of Art Museum Directors Board of Trustees President Lori Fogarty concurs. "Those proceeds should only be used for future acquisitions, to purchase things that will actually strengthen the collection. We also feel in the long run it’s going to be a real loss to that community."

Longtime donors, who have supported the museum mission for decades, may be inclined to agree.

Last but not least, Fogarty's opposition to deaccession on ethical grounds underscores the possibility of a chilling domino effect across the art and donor community. According to ArtWorld,

Museums that have engaged in similar types of deaccessioning in order to stabilize finances have been blackballed by peers. When the National Academy in New York sold a pair of Hudson River School pieces to cover its operating expenses in 2008, the Association of Art Museum Directors issued a censure of the institution—a first for the organization—telling all 180 of its members to stop collaborating with the academy.

Why would any donor rightly concerned with his reputation give to a blackballed museum?

On the other hand, museums can convincingly argue that selling such valuable work is in the best interests of the museum in the long term. Demographics and tastes change. Institutions can face the need to adapt or die. To echo Elizabeth McGraw's earlier sentiments, why would donors want to continue to prop up a flawed approach that's doomed to fail?

This line of thinking resonated with the Feigenbaum Foundation, which gave Berkshire $2.5 million to aid the transition (albeit before the deaccession controversy really exploded.)

One thing all involved parties can agree on is that it's not easy running a museum. Institutions find themselves vying for a tiny sliver of visitors' free time. They're fending off successful and deep-pocketed competitors. And, as is the case with Berkshire, they're literally struggling to keep the lights on. Desperate times call for desperate measures. Stakeholders understood the risks of deaccession, but they had no choice.

"Let’s face it. If we were not funding the plan in part by this financial strategy to deaccession and sell works of art, it probably would not have mattered," said Shields. "But at the end of the day, we are still in the art business."

The works are slated to be sold through Sotheby’s, New York, in either late 2017 or early 2018.

Related: Was It Legal for This Museum to Sell a Cezanne for $100 Million?