“Diversity of Treasures.” A Sunsetting Funder Shines a Light on Underrepresented Artists

/Back in June, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation announced it would close its doors and give the remainder of its holdings to museums.

At the time, it gifted approximately around 400 works—about half of its holdings—to New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art and 500,000 documents to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art (AAA). The AAA estimated it would take five to seven years to digitize the work and make it public.

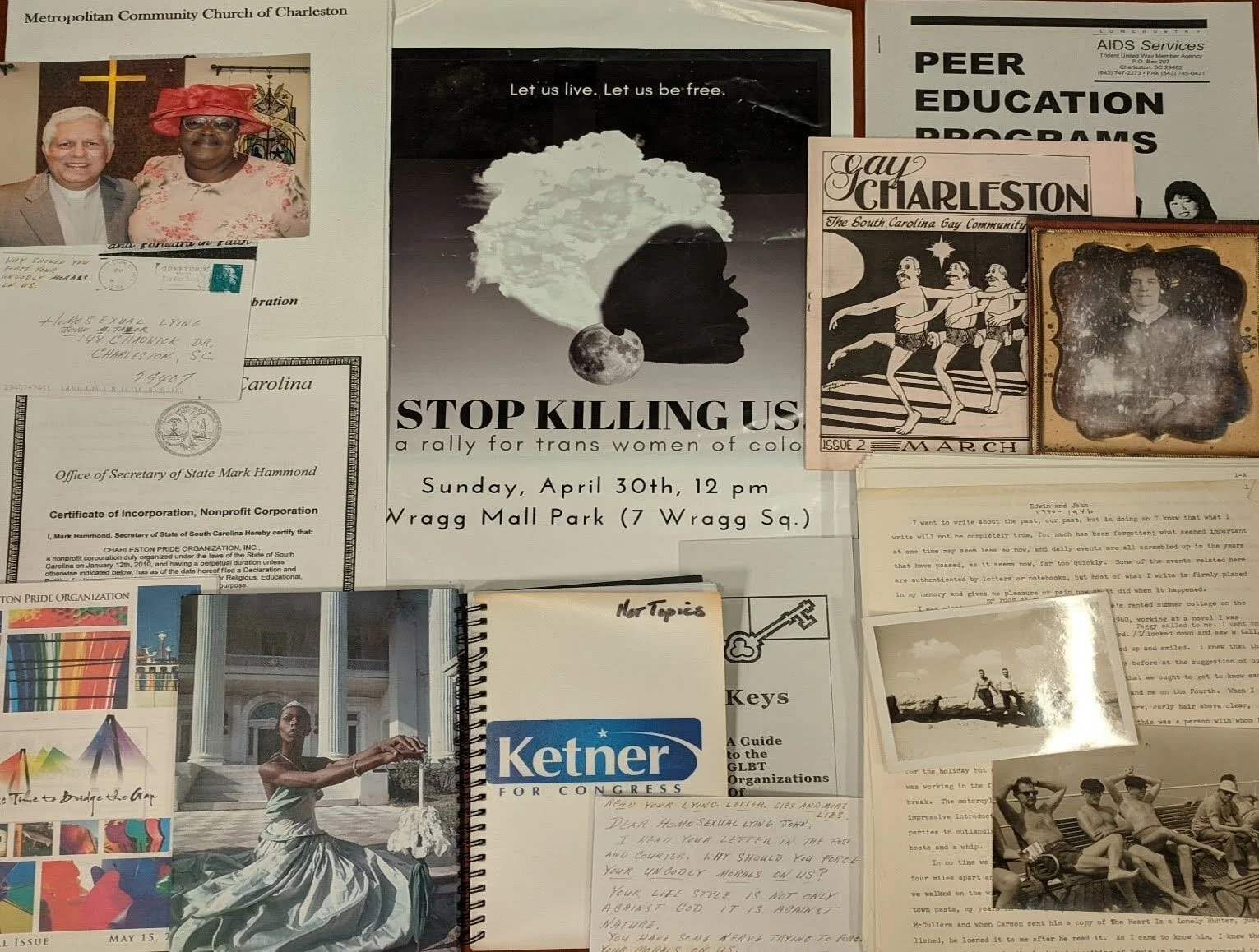

Now comes word that the foundation has made a $5 million gift to enable the AAA to create an endowment to process and digitize material on art and artists from “historically underrepresented groups” in U.S. museum collections. These groups include African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinos, Native Americans and women.

The gift helps the AAA match a 2016 Terra Foundation for American Art challenge grant to endow its digitization work, and there is much work to be done. To date, the AAA has been able to process only about 13 percent of its collections, which are continually expanding.

The AAA has been instrumental in giving voice to overlooked artists since its inception in 1954. When we last looked at the AAA, Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art had awarded the organization its inaugural Don Tyson Prize, a $200,000 award for outstanding achievement in American art.

While Crystal Bridges’ gift wasn’t earmarked for the AAA’s digitization efforts, there was some strong symbolism at play given who was cutting the check. Alice Walton and the Walton Family Foundation (where Alice serves on the board) are deeply committed to boosting accessibility, bringing more diversity to the museum world, and expanding the scope of what is considered American art.

The Roy Lichtenstein Foundation’s gift to the AAA is yet another example of a funder giving big to draw attention to previously underrepresented artists in a rapidly evolving arts philanthropy climate.

Mission Accomplished

In many ways, the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation’s dissolution seems counterintuitive. After all, artist-endowed foundations (AEFs) are emerging as a growing force in arts philanthropy. Rather than shutting its doors, shouldn’t the foundation be bankrolling more exhibitions and awarding more grants and prizes?

Not necessarily.

The foundation was launched in 1999 with the mission of facilitating public access to the work of Roy Lichtenstein and contemporary art. The foundation’s representatives and art world commentators believe it has accomplished this mission.

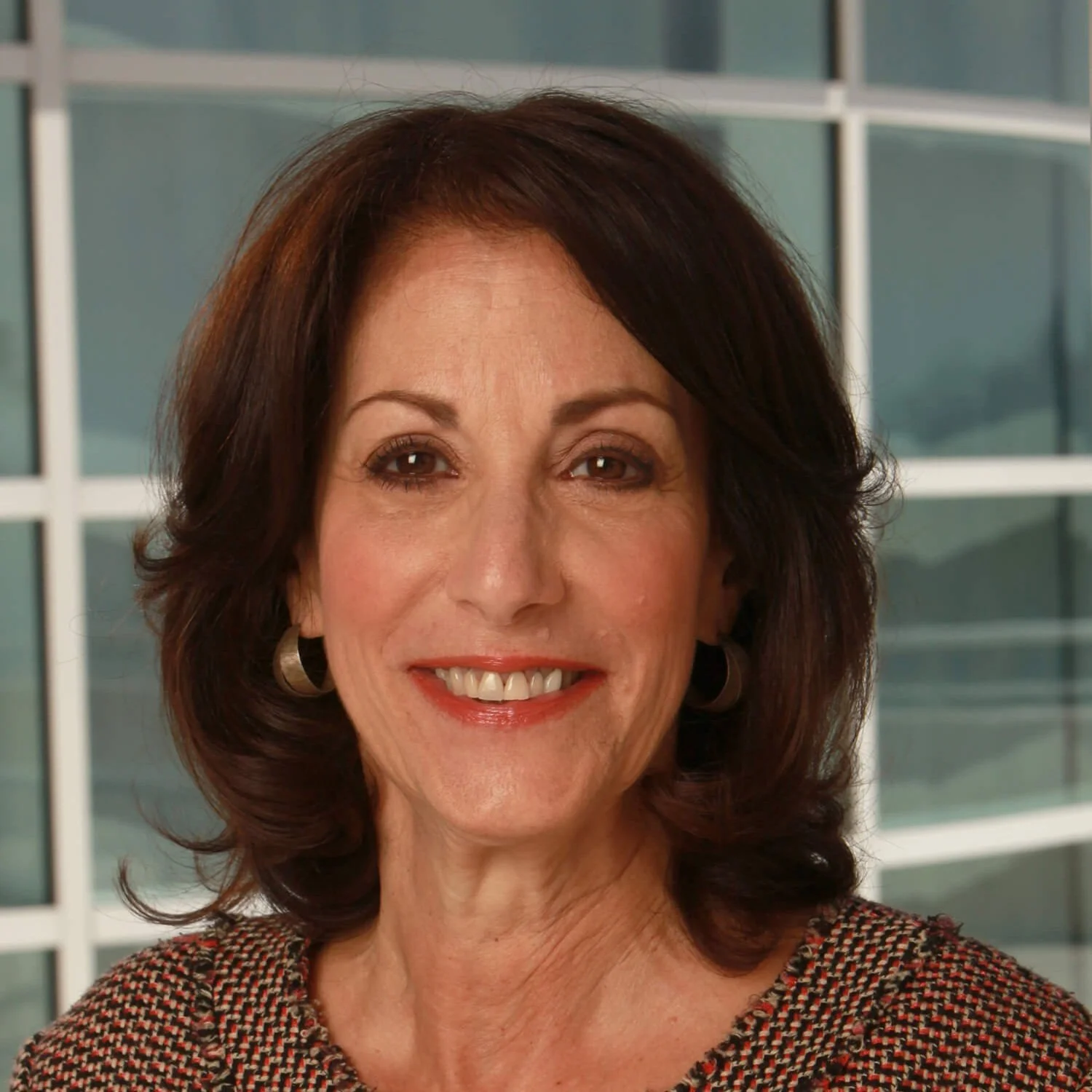

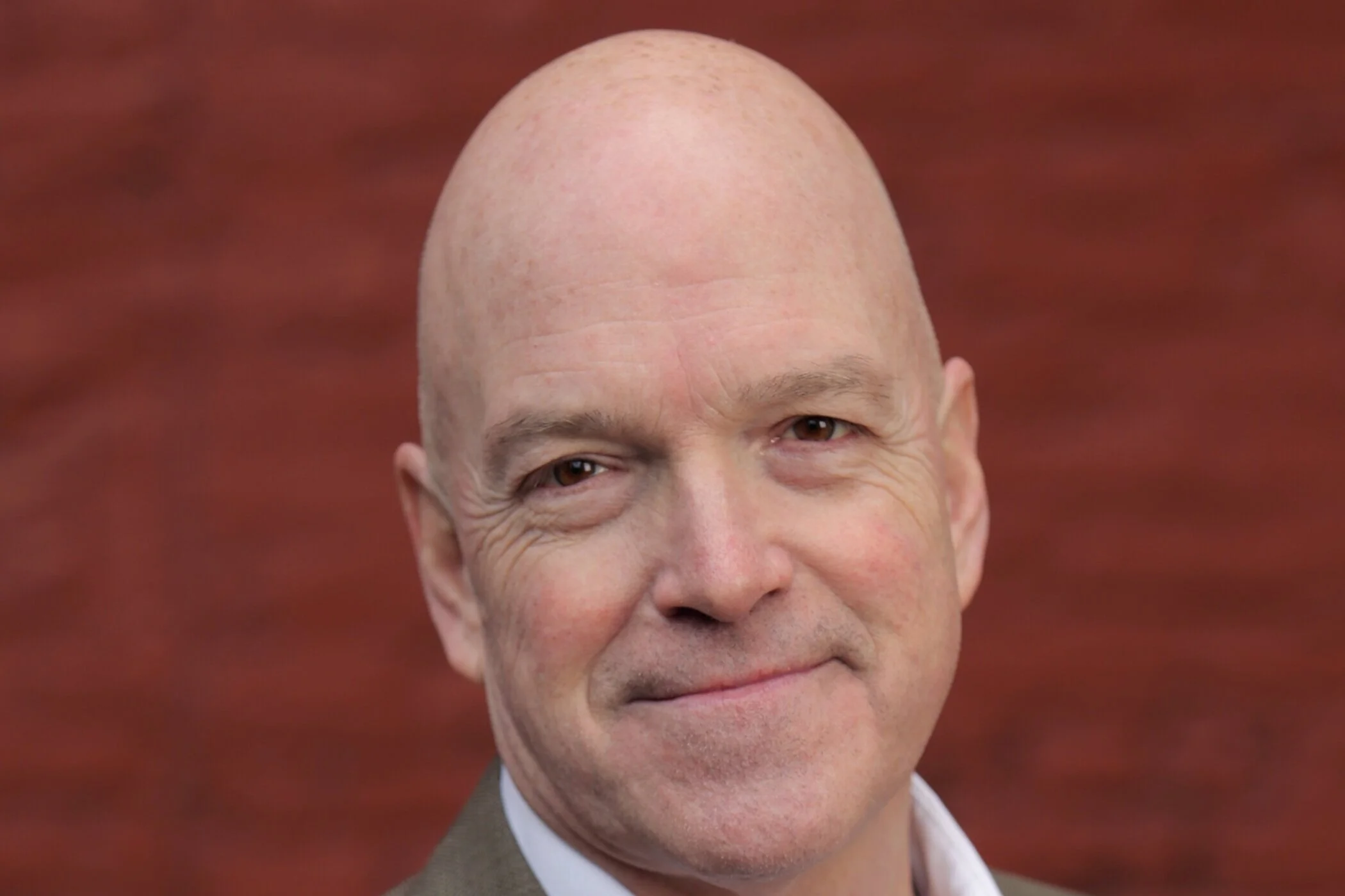

Speaking to the New York Times, president Dorothy Liechtenstein said the foundation was simply attempting to disseminate its namesake’s work and make it available to the public. “I like the idea of handing it off, and seeing what the future brings,” she said. Meanwhile, Jack Cowart, the foundation’s executive director, said, “We decided we wanted to get out of the art-holding business.”

Joan Mitchell Foundation CEO Christa Blatchford summed up the foundation’s thinking most succinctly when I spoke with her in early November. The foundation, she concluded, “made strategic decisions to sunset at a point when they feel the goals have been met.”

And speaking to the Times, Aspen Institute's Artist-Endowed Foundations Initiative (AEFI) project director Christine Vincent said, “The interesting thing about the Lichtenstein Foundation has been their heroic and imaginative efforts to give to networks and consortia around the globe. That ensures the work will be accessible to the public.”

Vincent highlighted the foundation’s role in acquiring and then donating an archive of some 200,000 prints, negatives and other material—dubbed the Harry Shunk and Shunk-Kender Photography Collection—to the Getty Research Institute, the Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery of Art, Tate, and Centre Georges Pompidou in 2013.

The “New Inclusivity”

In mid-November, David Hockney’s painting “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)” sold at Christie’s for $90.3 million, obliterating the auction record for a living artist.

While the sale generated breathless headlines, sales made prior to Hockney’s sale reflect an even more consequential development. Works from five African-American artists, two of them living, hit new highs the night before. For example, “Cultural Exchange” by Robert Colescott, the first African-American to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale, sold for $912,500, nearly triple his previous record.

Add it all up, and the sales, according to the Times, “signaled a new inclusivity in the art world, driven by a generational shift toward artists who have been out of the mainstream,” particularly nonwhite and female artists.

This “new inclusivity” in the art world isn’t—spoiler alert!—driven by good intentions alone, but rather, a confluence of market forces. Established names continue to command stratospheric prices, shutting out mid-market buyers. At the same time, most pieces considered “masterworks” are off the market entirely, generating demand for previously overlooked contemporary work.

Yes, the market has spoken, but we shouldn’t neglect philanthropy’s role in this development, either, particularly when it comes to AEFs like those representing Roy Lichtenstein, Joan Mitchell and many others. Some of these foundations have become important advocates for underrepresented artists. For example, Christa Blatchford of the Joan Mitchell Foundation talked to us about that institution’s role as an “artist-endowed foundation that stewards the legacy of a female artist,” and noted that heightened recognition of Mitchell’s work has aligned “with a larger reassessment of male-dominated art historical narratives to look more closely at women artists, artists of color, and LGBTQ artists.”

The Home Stretch

As for the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, details remain scant in terms of how and when its wind-down will officially, well, wind down.

The foundation continues research for its production of a web-based catalogue raisonné of all Lichtenstein work, and according to the AAA, “additional national and international art and collection partnerships are being planned for the coming years.”

Its holdings still stand at around 400 works, and I suspect that as you read this, the foundation’s phone is ringing off the hook.

More grants may be on the horizon, as well. As a point of reference, 2018 grants included $100,000 to Film Forum to established an endowed fund for showing firms about art and artists, $25,000 to the Colby College Museum of Art and the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University to support “The Early Work of Roy Lichtenstein,” and $7,500 to the Whitney to assist curatorial research.

It’s also worth noting that prior to its AAA gift, the foundation’s largest gift in 2018 was $100,000 to the Film Forum. In 2017, it pledged a six-year, $300,000 grant to the Columbus Museum of Art to fund the Roy Lichtenstein Curatorial Fellowship. And in 2014-2015 it donated $250,000 to the AAA as lead support to digitize a portion of the Leo Castelli Gallery records.

Each gift is impressive in its own right, but clearly, none of them approach the magnitude of its $5 million commitment to the AAA. This, not surprisingly, is what happens when a foundation decides to turn out the lights.

“We applaud institutions like the archives that open their virtual doors wide and invite the world in,” Dorothy Lichtenstein said in a statement. “Having this diversity of treasures available online will allow students, scholars and art lovers to explore and expand on the remarkable network of connections and associations across the vibrant arc of American art history.”

In related analysis, check out our take on philanthropist Madeleine Rast’s $9 million bequest to the National Museum of Women in the Art.