Build On: Why Reports of the Death of Big Capital Projects are Greatly Exaggerated

/Heather Shimmin/shutterstock

Recents developments out of New York City provide an insightful look into the contrasting and evolving fortunes of legacy institutions embarking on audacious capital projects.

On one hand, organizations like the Lincoln Center and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met), citing exploding costs and tepid donor support, either shelved or dialed back ambitious renovation projects, suggesting that “bigger” isn’t always “better.”

On the other hand, there’s the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In 2016, while The Met was planning budget cuts, David Geffen gave MoMA $100 million for its $450 million renovation and expansion project. Last summer, the museum revealed its final design for the project, which will increase exhibition space by 30 percent and add flexible spaces dedicated to contemporary design, performance and film. A few months later, it netted a $50 million gift from Steve and Alexandra Cohen.

And now comes word that Debra and Leon Black have chipped in $40 million to create the Debra and Leon Black Family Film Center at the MoMA. “As a lifelong lover of film,” Mr. Black said in a statement, “my family and I are honored to have our name associated with the Film Center of this great institution.”

Maybe it pays to go big, after all?

Finance, Poetry, and Painting

Leon Black was named chairman of MoMA last spring, having shared the title since 2015 with real estate mogul Jerry Speyer. Black is also a big-time art collector. In 2012, he famously paid $119.9 million, then a record at the time, for one of four versions of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.” A few months later, he put the painting for six months of public exhibition in MoMA.

With a net worth of roughly $6.9 billion, Black is the co-founder, chairman and CEO of private equity behemoth Apollo Global Management, which manages $269 billion in assets. The Blacks’ giving, which flows through the Leon Black Family Foundation, primarily focuses on health and arts-related causes.

Black, who endowed professorships in Shakespearean Studies at his alma mater Dartmouth, has been extolling the virtues of the humanities since long before fellow Wall Street types and Silicon Valley executives found it fashionable (and good for business). At the Forbes 400 summit on philanthropy, Black said, "Especially in the world today, where science rightfully is so important in terms of technology, innovation, telecom, internet, fighting diseases, I think it’s equally important that poetry and painting have their share of support."

I’d humbly add “philosophy” to the list as well. Earlier this year, finance titan Bill Miller gave $75 million to Johns Hopkins University's philosophy department. Upon doing so, he said it would be “great” if other rich people who once studied philosophy followed his lead. He mentioned Leon Black by name.

Black’s 2012 gift to Dartmouth was particularly appropriate and portentous. Black gave the school $48 million for construction of the Black Family Visual Arts Center, a center that has allowed film, media studies, and studio arts students to study under the same roof.

Similarly, by creating the Debra and Leon Black Family Film Center, his latest gift to MoMA will present film exhibitions and premieres with directors, actors, and other cinema experts in multimedia galleries and two state-of-the-art theaters in the Ronald and Jo Carole Lauder Building.

A Focus on Access

MoMA’s expansion project will be completed in 2019, and its fundraising success comes at a time when arts funders are increasingly concerned about measuring impact, backing activist art projects, and engaging disenfranchised audiences.

Foundations, rather than patrons, typically lead this charge, since, as the Bridgespan Group has pointed out, individual donors tend to lack the infrastructure, relationships, and expertise needed to make big bets to drive social change. So when patrons do cut big checks for huge capital projects, they often do so with an eye toward the low-hanging fruit—boosting access to the arts.

The new Black Family Film Center aims to get more bodies in the door by building on the MoMA’s legacy in the cinematic arts. “Throughout its remarkable 89-year history, MoMA has established the highest reputation in building a great film library, being at the forefront of film conservation, and leading the way with groundbreaking film openings,” Black said in a statement.

Meanwhile, Kenneth Griffin, yet another hedge fund billionaire, recently gave $16 million to the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida. The museum’s expansion, he said, “will create a wonderful opportunity for generations of Palm Beach families, students, and visitors to learn about and enjoy art.”

Griffin also gave MoMA a $40 million unrestricted donation about three years ago.

Even as billionaires fuel MoMA’s big ambitions, not everyone is thrilled with the museum’s priorities. Back in June, about 100 MoMA workers and supporters, some of whom chanted “shiny new building, shabby old wages,” rallied outside the museum as donors and trustees met to discuss stalled contract negotiations.

Protesting staff wondered how the museum could afford a $450 million renovation and expansion project, but couldn’t afford to cover the costs of its workers’ healthcare. “There’s a lot of uncertainty around that issue, and our members need these costs alleviated,” said Athena Holbrook, a collections specialist and member of the union’s bargaining committee.

In mid-August, parties settled on a five-year contract that addressed issues like employee health benefits, salary raises, and opportunities for upward mobility.

The Capital Project is Dead; Long Live the Capital Project

By forging a new contract with its employees, MoMA underscores a cardinal rule of arts philanthropy: donors like stability. Aware that big capital projects can go over-budget, many donors quite understandably want organizations to have their labor and financial houses in order before they reach for their checkbook.

Which brings me back to Lincoln Center and The Met.

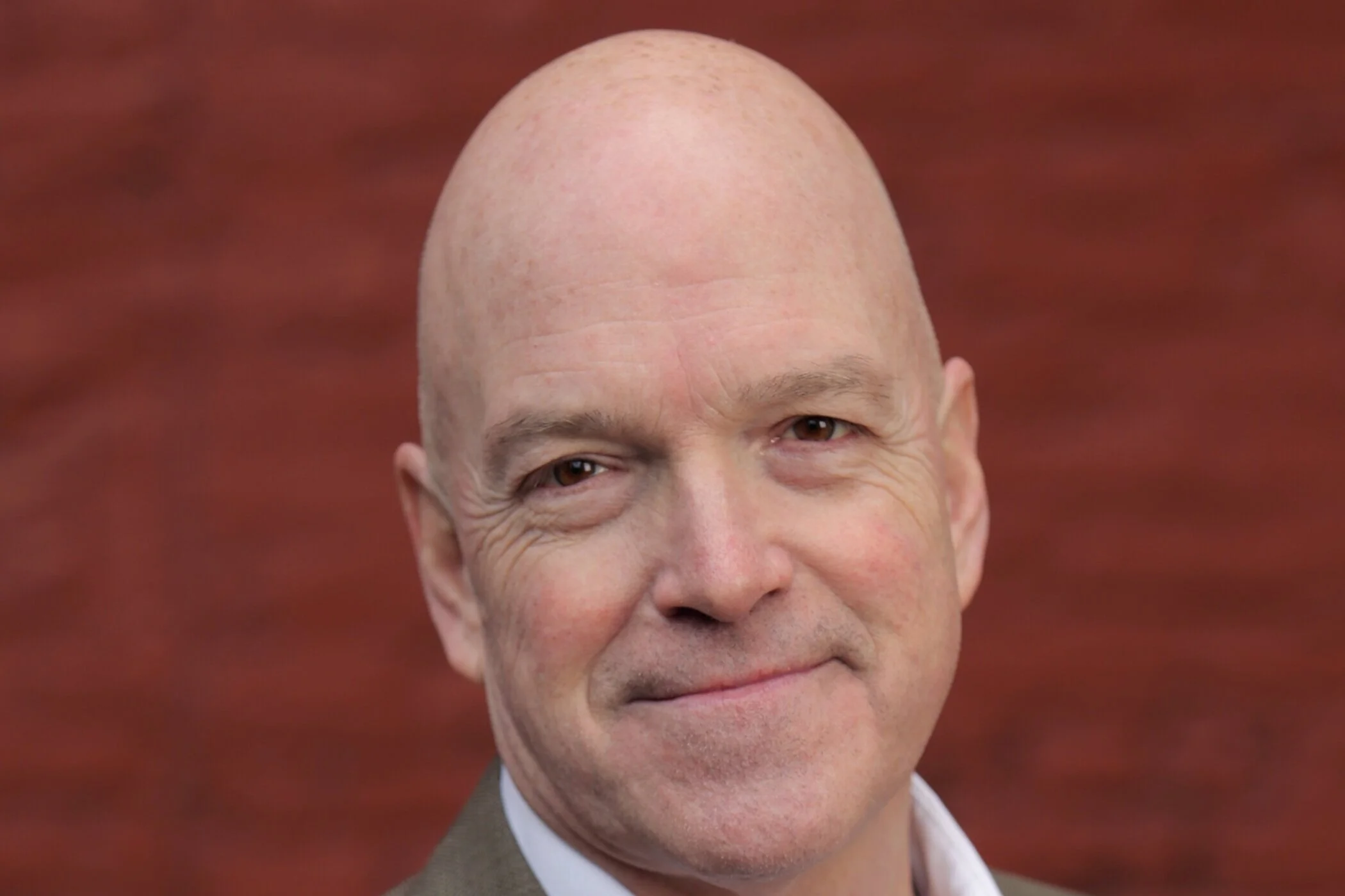

The Met, faced with a $10 million deficit, delayed a $600 million capital project to redesign its modern and contemporary art galleries early last year. (Daniel H. Weiss, The Met’s president and chief executive, subsequently pegged the cost at $800 million.) In lieu of the announcement, the museum went back to the drawing board. According to Weiss, The Met was able to increase revenue, reduce costs, boost transparency, and improve communication between the administration and the staff.

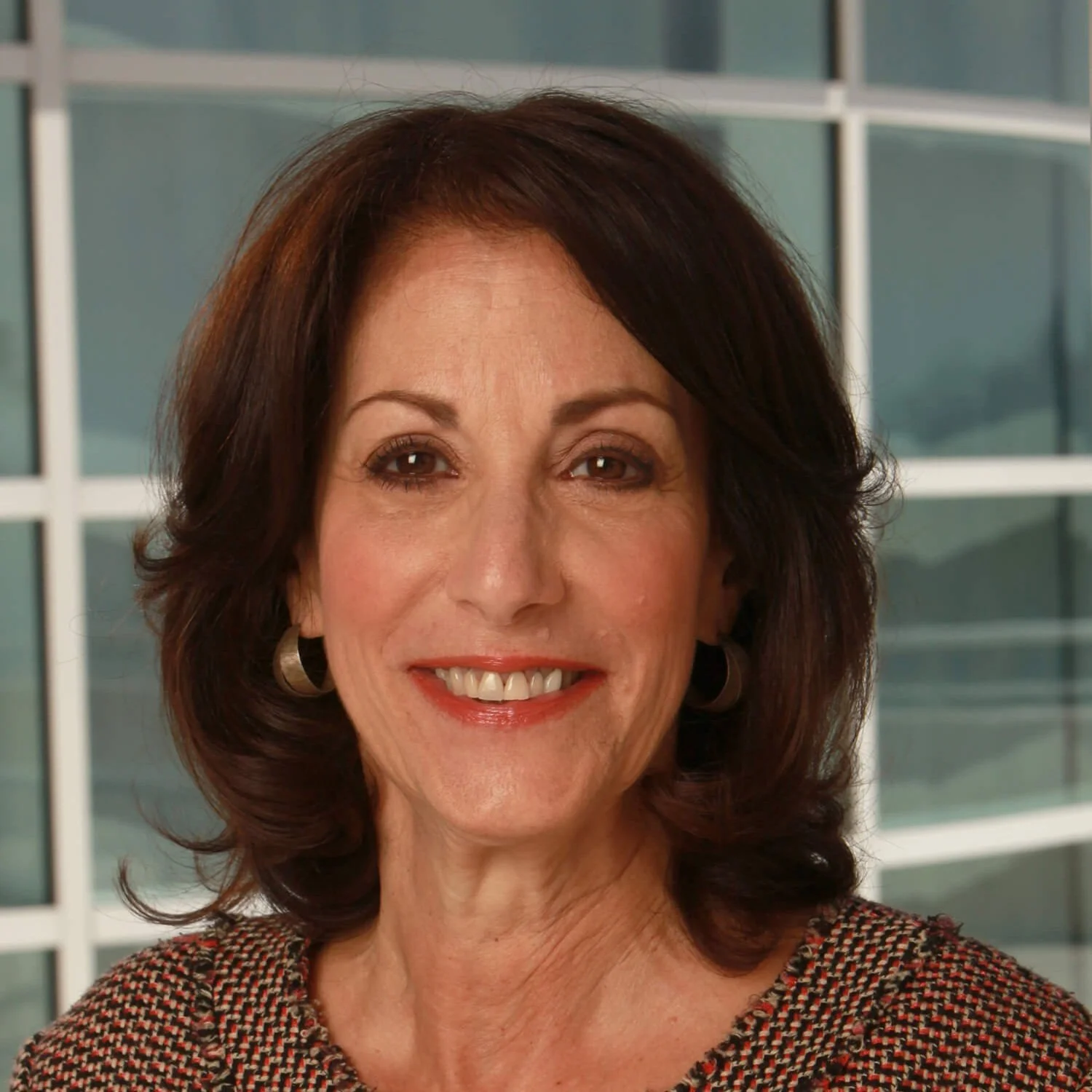

Late last year, it was rewarded with an $80 million gift from trustee Florence Irving and the estate of her husband, Herbert Irving. The same week, Lincoln Center announced $50 million in new donations. The haul came after new president Deborah Borda pushed the New York Philharmonic to rethink the costly Lincoln Center renovation plans.

In other words, two cash-strapped legacy institutions, within the same week, announced impressive gifts after shelving controversial capital projects and streamlining its operations. The lessons here are obvious. Donors value sound financial stewardship. Less is more. Expensive capital projects aren’t worth the trouble. In a world of rising inequality, those millions can be best allocated elsewhere.

Then again, maybe not.

In mid-November, The Met announced that it had reactivated its plans for a modern and contemporary art wing, albeit in a scaled-back form, thanks in part to its new (and controversial) admissions policy, which contributed to a 41 percent increase in revenues, and its decision to turn over The Met Breuer to the Frick Collection as of 2020.

The museum is on track to balance its $320 million annual budget by 2020, and more projects are in the works, including a revamp of its Michael C. Rockefeller Wing ($70 million), the renovation of its galleries of British decorative art and sculpture ($22 million), and the installation of new skylights in its European paintings galleries ($150 million).

As for the “scaled-back” form of its revived modern and contemporary art wing, The Met’s Weiss said the Southwest Wing, as noted earlier, came with an original price tag of $800 million. The revised project is estimated to cost $600 million—the same price The Met gave when it announced its plan to delay construction in January of 2017.

Critics again point out that The Met’s project is somewhat redundant. New York City already has a formidable number of museums devoted to modern and contemporary art, like, say, the Museum of Modern Art. Will donors get back on board, especially given all the other pressing social and equity-related challenges out there?

It sure seems like it. Fundraising for the resuscitated project is advancing “to the next level,” Weiss said, though he would not be more specific on timing or a possible lead gift.