The Future Is Now: Behind the Surge In Los Angeles Arts Philanthropy

/photo: Alex Millauer/shutterstock

On the heels of his recent $150 million gift to the Los Angeles County Museums of Art (LACMA), David Geffen told the Los Angeles Times, "Los Angeles is the city of the future."

He wasn't lying. And, in part, that future is being fueled by a rising tide of big league philanthropy.

Roughly four months after Geffen provided the LACMA's $650 million capital campaign with a much-needed infusion, the museum announced plans to create a satellite campus, or possibly two, in South Los Angeles.

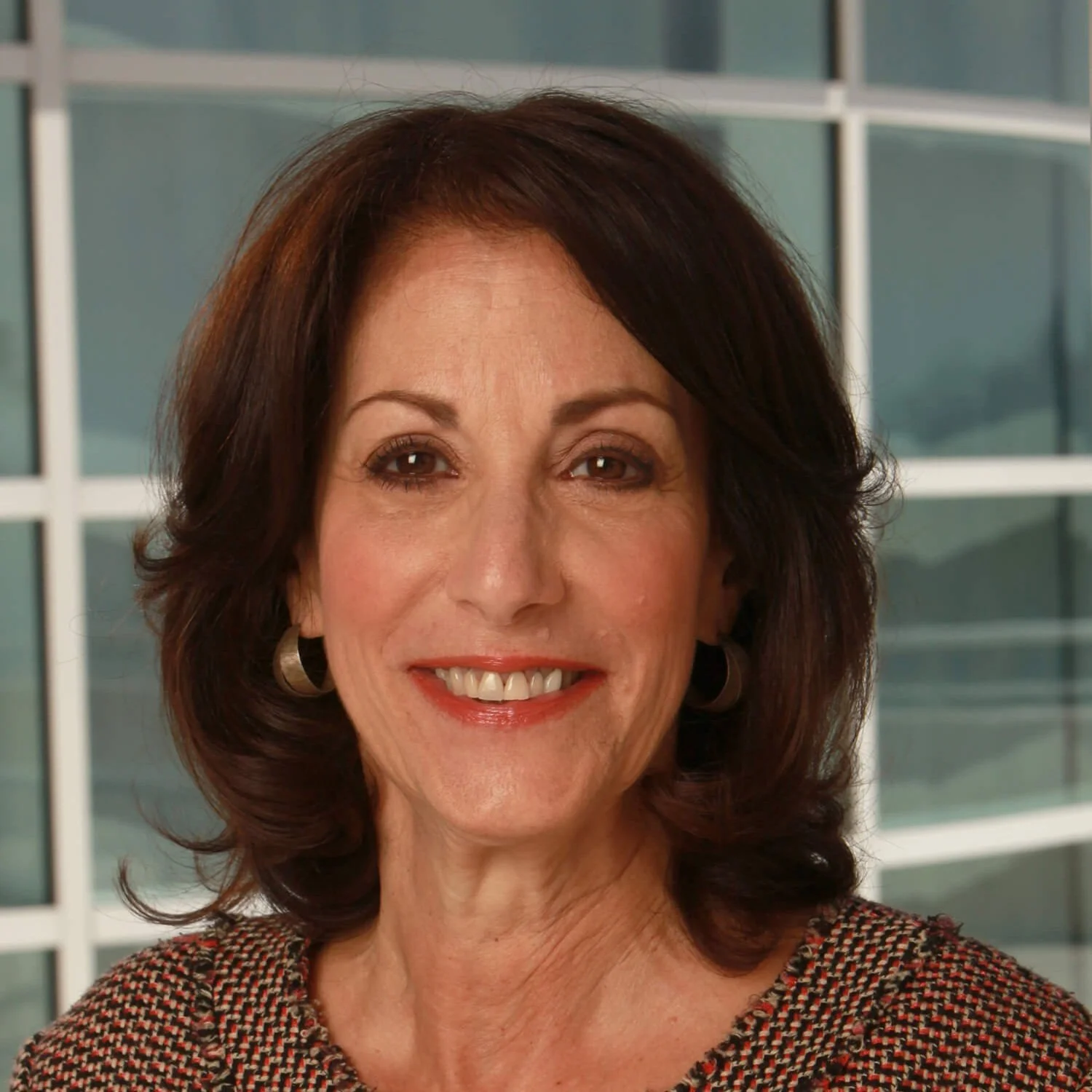

Around the same time, the Hammer Museum announced the largest gift in its history: $30 million from L.A. philanthropists Lynda and Stewart Resnick toward an ambitious renovation and expansion. The museum also announced that board chairwoman Marcy Carsey donated $20 million, a gift made about a year ago, but not made public until mid-February.

Move over, Eli Broad. While Broad long groused about Los Angeles being a "one-philanthropist city"—namely, him—he now has much more company, which explains his recent retirement from public life. When Broad first arrived in L.A. to expand his homebuilding company decades ago, the city's art and museum scene was virtually nonexistent. Now, it's flourishing.

The clicking sound you hear is that of hundreds of New York City museum professionals sprucing up their LinkedIn profiles and firing off resumes to the ever-growing list of well-funded Los Angeles museums.

I'm kidding, of course. But only slightly. The Los Angeles museum gold rush isn't just financially impressive; it flies in the face of prevailing conventional wisdom.

L.A., we're told, has too many museums. Why are they expanding in a city already known for its many entertainment options, and where traffic makes it hard to get anywhere? Furthermore, massive capital projects almost always backfire. Costs escalate, donors jump ship, and museums plunge deeper into debt.

Look no further than the plights of the New York Philharmonic and Metropolitan Museum of Art, both of which had to shelve costly and controversial capital projects.

So why is the Los Angeles arts ecosystem breaking all the rules? For an answer, let's take a closer look at the LACMA's expansion plans. (I'll explore the Hammer gift in greater detail in a separate post.)

The goal of LACMA's expansion, according to director and resident "provocateur" Michael Govan, is to reach "underserved" populations in Los Angeles by transforming an 84,000-square-foot building into a center for a variety of community-targeted arts programming. The new site will initially serve about 9,500 students who don’t live near its mid-Wilshire campus.

"If you look at a map of L.A.’s public schools, the dots representing the neediest students are all through South Los Angeles," Govan said. "You start thinking, where can the value of your collection and program be the greatest, when you’re behind a big fancy fence on Wilshire Boulevard or out in the community?"

Govan cited another slightly more prosaic reason for the new location: the LACMA currently pays for offsite commercial storage, with no such facilities under its own control. A new site could have built-in storage, if renovated to meet standards.

This may sound like a relatively uninspiring reason for building a new campus, but it's actually pretty important. Museums have too much art and not enough space. This is one of the main reasons why collectors like Guess co-founder and fellow Angeleno Maurice Marciano, who recently declared "Los Angeles is getting to be like the art center of the world," started his own museum.

Of course, more storage doesn't translate into increased viewership. But at the very least, the space may come in handy as the museum transforms its main Wilshire campus, which involves razing three existing buildings to replace them with a single dramatic structure by the architect Peter Zumthor.

Add it all up, and Govan estimates the museum will need $25 to $30 million in capital investment for the new facility.

The museum needed permission from the City Council since 25 percent of its funding comes from the county. "I don’t see any real obstacles," said councilman Curren D. Price, Jr., prior to the vote, before alluding to the project's larger, creative placemaking-like impact: "LACMA’s presence here is going to be very, very significant—part of a larger corridor for arts, recreation, and education."

In late January, the council officially approved the plan.

So far, so good, right? Right. But I can't help but wonder: Does the museum want to add another capital campaign to its plate? After all, despite Geffen's $150 million, the museum is still $200 million short of its stated budget for construction and related costs.

Govan isn't too worried, and I think his confidence is justified.

For starters, the plan is practical, and, relatively speaking, affordable. Thirty million dollars is a reasonable fundraising goal, especially if the county kicks in 25 percent.

The Ford Foundation has already issued a $2 million flexible grant to LACMA "for the acquisitions of sites and community-based programming" in South Los Angeles. Darren Walker called the project "a radical idea," not being done at this scale by any museum in America.

“By going right into the community, this turns the traditional, elitist museum model on its head," he said.

Ford's involvement and stamp of approval is important, because when Ford leads, other equity-minded funders often follow.

To that end, Govan told that the Times' Jori Finkel he doesn't envision much donor overlap between the museum's concurrent capital campaigns, noting that the South L.A. projects appeal to those supporting "a different set of national initiatives toward social justice."

Govan's comments also underscore an even larger narrative at play. He's probably not too worried about raising the money because his museum is based in Los Angeles. The city is flush with deep-pocketed, motivated, and highly enthusiastic art donors more than happy to fund projects like the LACMA's and Hammer's expansions.

The phenomenon can be partly explained by mundane market dynamics. Museums are raising more money than ever. Fundraising is now a perpetual process, rather than an activity with a fixed endpoint. The stock market has lifted donor portfolios. And as Govan noted, donors are increasingly drawn to the kind of inequality-combating programming being offered by museums like the LACMA.

Then again, Los Angeles isn't your average city.

Consider geography. The notoriously sprawling city has vast swaths of underleveraged neighborhoods like South Los Angeles. Developers can build horizontally rather than vertically.

Los Angeles is also enjoying an influx of new artists, stimulating demand. "I think you find more young artists living in Los Angeles today who, decades ago, would have been in New York," the native Brooklynite David Geffen said after his gift to the LACMA last year.

Geffen's statement applies to museum professionals, as well. According to Robin Pogrebin, writing in the Times, the city's three main art museums—the LACMA, the Hammer and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles—are now all run by former New Yorkers.

But perhaps the biggest reason why Los Angeles is experiencing a surge in giving is simply due to history. The city, having long stood in the shadows of the Big Apple, is finally experiencing a growth spurt.

As Pogrebin noted, movies have traditionally been its dominant industry. As a result, the city has lagged behind older East Coast counterparts, where museums—and with them, cultural philanthropy—have been around for decades, if not centuries.

"We’re almost 100 years behind New York—we’re still young by museum and civic standards," Govan said.