"Without Shackles." Behind an Exceedingly Rare Unrestricted Museum Mega-Gift

/Art Institute of Chicago. photo: MaxyM/shutterstock

It's no secret that the large majority of grants that flow from foundations are for restricted project support. Many gifts from big individual donors also go to support very specific things, like a new hospital wing or university research center. Still, after years of pleas by nonprofit leaders for more general support, we're finally seeing signs that more mega-donors embrace "no strings attached" giving across the broader world of philanthropy.

For example, quite a few philanthropists who are tackling social and economic challenges bring a venture capital mindset to this work, looking to scale effective organizations with big chunks of general support cash.

There are fewer cases of top donors offering this kind of support to cultural or higher ed institutions. But they do pop up, and seemingly with more frequency—like Kenneth Ricci's $100 million unrestricted gift to the University of Notre Dame last year. Or the unrestricted $140 million gift from an anonymous donor to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology last year.

Then there was Kenneth Griffin's $40 million unrestricted gift to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) back in 2015.

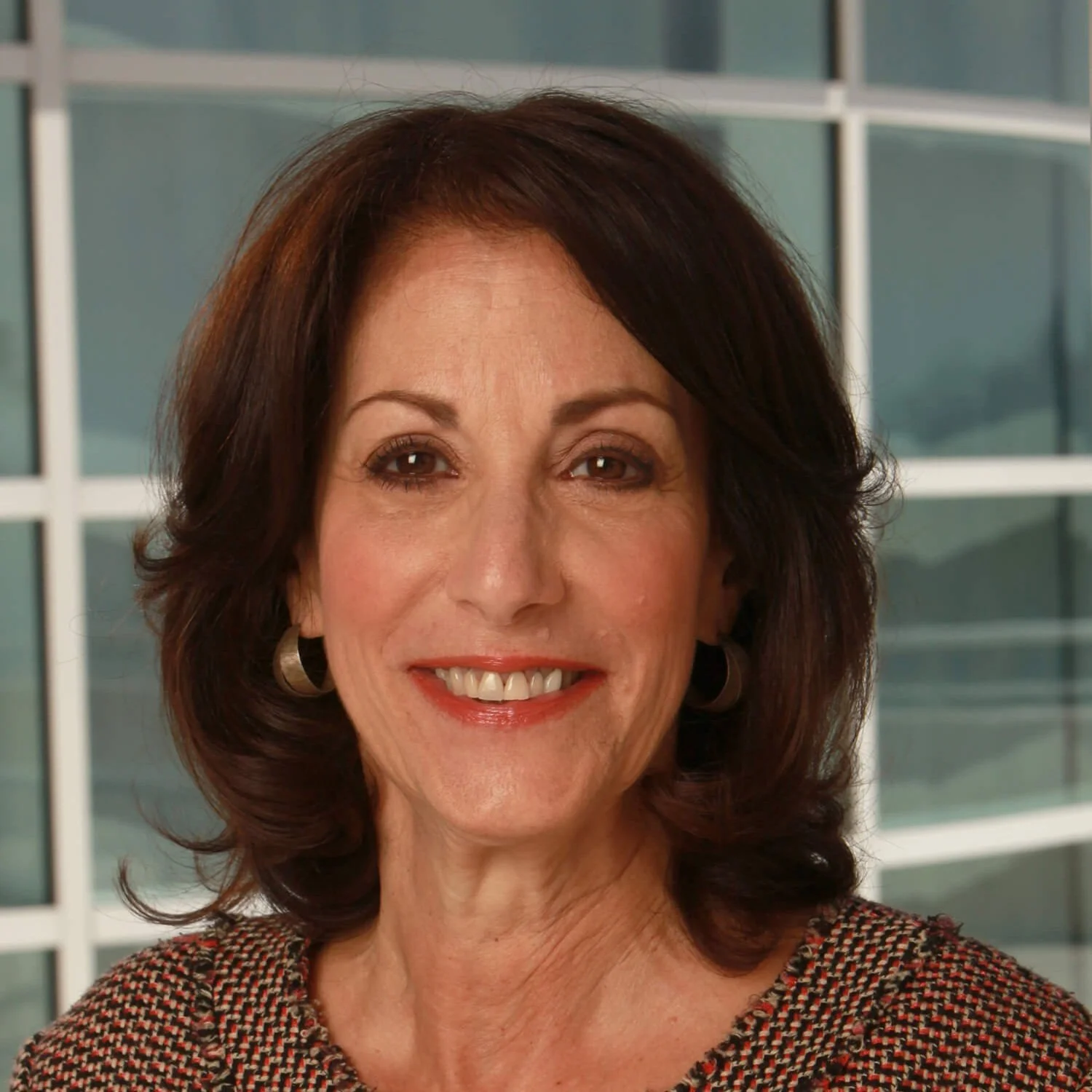

Most recently, comes news of a $50 million unrestricted gift from Janet and Craig Duchossois to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Are we seeing an actual trend here?

First, some background. Craig Duchossois is chief executive of the Duchossois Group, a holding company with interests in consumer products, technology and service businesses, while Janet serves on the institute's board of trustees and is deeply involved with its work.

The family name may ring a bell to IP readers.

Earlier this year, we named the Duchossoises as one of "Three Philanthropic Couples with Chicago Connections to Watch in 2018." Given Craig's CV and his family's deep record of giving in and around the city, it wasn't an outlandish prediction.

Craig serves on a litany of nonprofit boards, including the Culver Educational Foundation, Illinois Institute of Technology, and the Chicago Council on Global Affairs. He also serves on the University of Chicago's board of trustees. Meanwhile, the Duchossois Family Foundation has provided support to the Boys and Girls Club of Chicago, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Greater Chicago Food Depository, and WTTW Chicago Public Media.

Last May, the family made a $100 million gift to establish The Duchossois Family Institute at the University of Chicago Medicine. The amount was the largest single gift in support of UChicago Medicine and brought the family's lifetime charitable contributions to the medical center to $137 million.

As for her family's unique gift to the Art Institute of Chicago, Janet said, "Craig and I chose to make this unrestricted gift to demonstrate our confidence and support" of institute President James Rondeau and the board. "We are proud to be partners in their strategy and approach for the museum, both today and in the future."

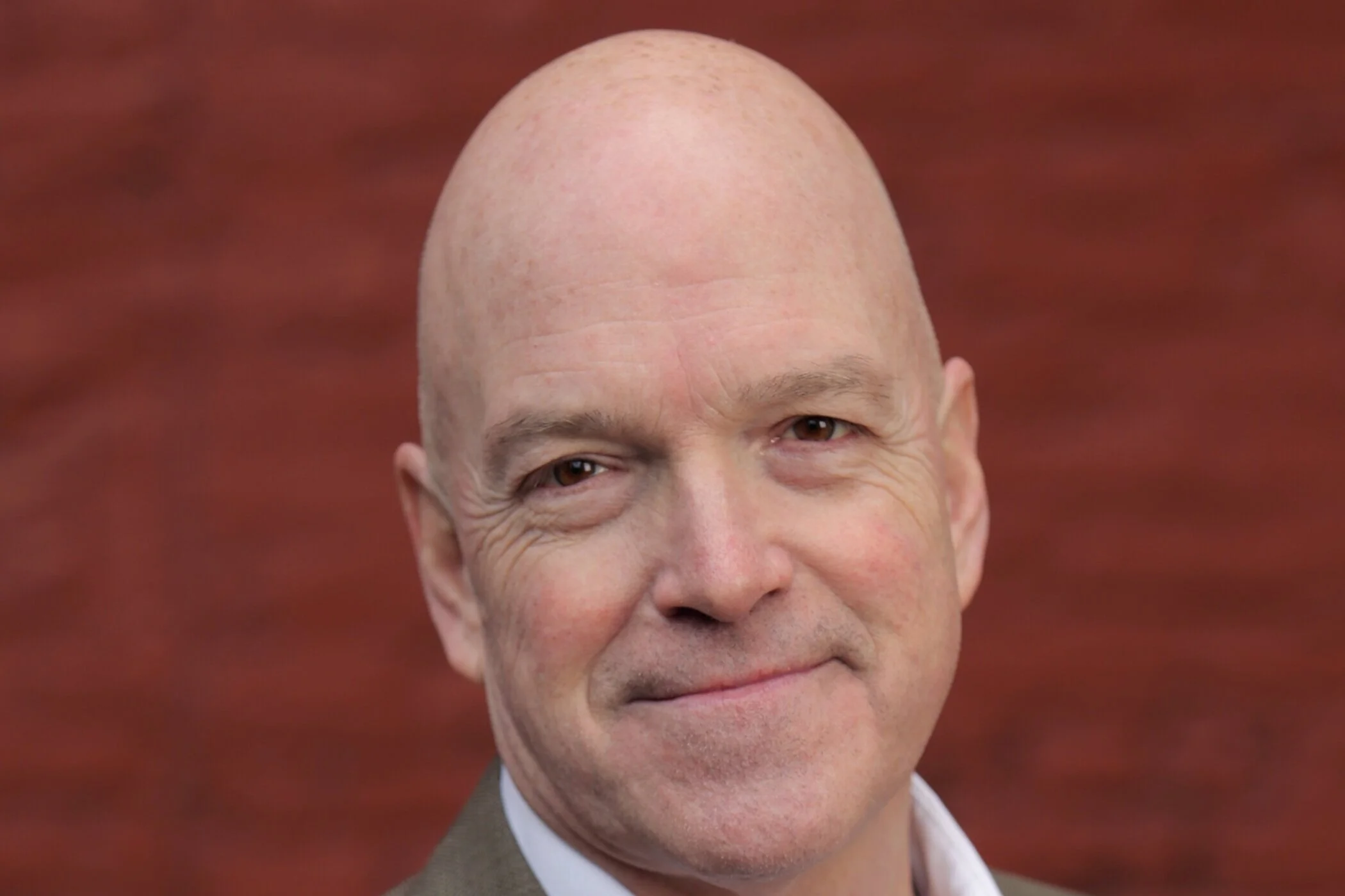

The institute also announced it received a $20 million gift from Robert and Diane v.S. Levy. The gift was earmarked for acquisitions and operations.

Robert Levy is in his second term as chair of the Art Institute's board of trustees and is a retired partner, chairman and chief investment officer for U.S. Equities at Harris Associates L.P. He also serves as president of the Robert M. Levy and Diane v.S. Levy Family Foundation.

Levy said that he hopes the family's gift will "provide support to limit future price increases. For us, access is a very important issue." (In June 2015, general admission at the institute went up to $20 for Chicago adults, $22 for Illinoisans, and $25 for those from outside the state.)

The Levy case study underscores why donors remain smitten with gifts earmarked for a specific purpose. Their gift doesn't just support the red-hot issue of access; it supports the Levys' definition of access. This distinction may seem subtle, but it's important in an arts philanthropy space where donors have tackled the issue from different angles.

To Alice Walton, access means providing residents of Northwest Arkansas with world-class museum-going experience. To the Shelley & Donald Rubin Foundation, it means supporting arts organizations that serve traditionally under-engaged "at-risk communities."

And to the Levys, access is linked to financial barriers to museum entry. The couple can sleep soundly knowing that their millions will address a measurable challenge that has been resonating across the donor community in the wake of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's new paid admissions policy.

The same cannot be said for the unrestricted Duchossois gift.

According to president Rondeau, there are no specific or immediate plans for the new money, but he told the Chicago Tribune it could be influential in shaping the museum's future. The museum’s long-range plan includes the possibility of a new building devoted to Rondeau's area of expertise, Asian art.

Rondeau's comments illustrate why unrestricted gifts are so rare in the museum world. Its inherent vagueness, coupled with the specter of a high-risk capital project, would give many donors a severe case of heartburn.

Then again, the Duchossoises aren't your average donors.

Craig said he wanted the institute to use the money "without shackles," noting that its unrestricted nature "maximizes the flexibility" and "strategy" for president Rondeau. The institute, he said, "presented to Janet and myself a campus vision that is extraordinary."

To which other museum directors are likely saying, "But we also have an extraordinary vision! Why haven't we received a giant unrestricted gift?"

By this point, the reasons for this should be self-evident. Foundations and patrons like the Levys have a deep affinity for a specific cause or capital project. They want to fund a program that directly affects change. They want to be sure their money is spent wisely. They like measuring progress against clearly defined goals. They like having control.

Could more patrons follow the lead of the Duchossoises and award museums unrestricted grants in the future? Corresponding psychographic data across the larger giving space provides cause for cautious optimism.

A recent study titled "Going Beyond Giving" by the Philanthropy Workshop found that despite their reputation as hard-nosed business types, many high-net-worth donors don't care all that much about metrics. We've often found the same thing in our reporting on the new philanthropists, who often place a greater premium on leadership and vision. So maybe it's just a matter of time before we see a notable uptick in general support within the high-stakes world of museum fundraising as part of a broader shift in how donor dollars flow.

Or maybe not. The museum world isn't typical of the nonprofit sector, with characteristics that militate in favor of restricted giving.

Despite the well-documented financial risks, many museums, unlike organizations focused on K-12 education or climate change, remain beholden to massive capital projects. A recent study of 75 museums across 38 countries by Quartz magazine found that when it came to building new wings and galleries, the U.S. spent more than all the 37 other countries combined.

And as sure as the sun rises in the east, donors love to fund big capital projects. To quote Neal Benezra, the director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which has raised more than $610 million in its own capital campaign: "Patrons are also more likely to stump up for a splashy expansion than for a lower-profile renovation or acquisition."

Recent history corroborates this. Most patron mega-gifts in the museum space typically flow to high-profile capital projects rather than the far less splashy unrestricted rubric. Even Kenneth's Griffin's unrestricted gift to the MoMA should be viewed within this context. His gift came in the midst of the museum's ambitious and controversial $93 million expansion effort, leading to a perception that perhaps the gift was "unrestricted" in name only.

This mutual affection for capital projects may also explain why museums rarely net significant unrestricted gifts while other organizations are benefitting from greater donor interest in general operating support.