A Mental Health Funder Looks to Rural Texas as It Shifts Upstream

/photo: Paul Quinn/shutterstock

The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health recently announced the five Texas counties that will receive $2 million in grants to focus on addressing the root causes of mental health in their communities. The grants come as the foundation shifts its strategy away from dealing with mental illness directly and toward addressing the underlying social and economic factors that influence mental health in the long term.

Grantees are expected to reach out to and include community members who have been left out of this type of conversation in the past. The goal is greater mental health equity.

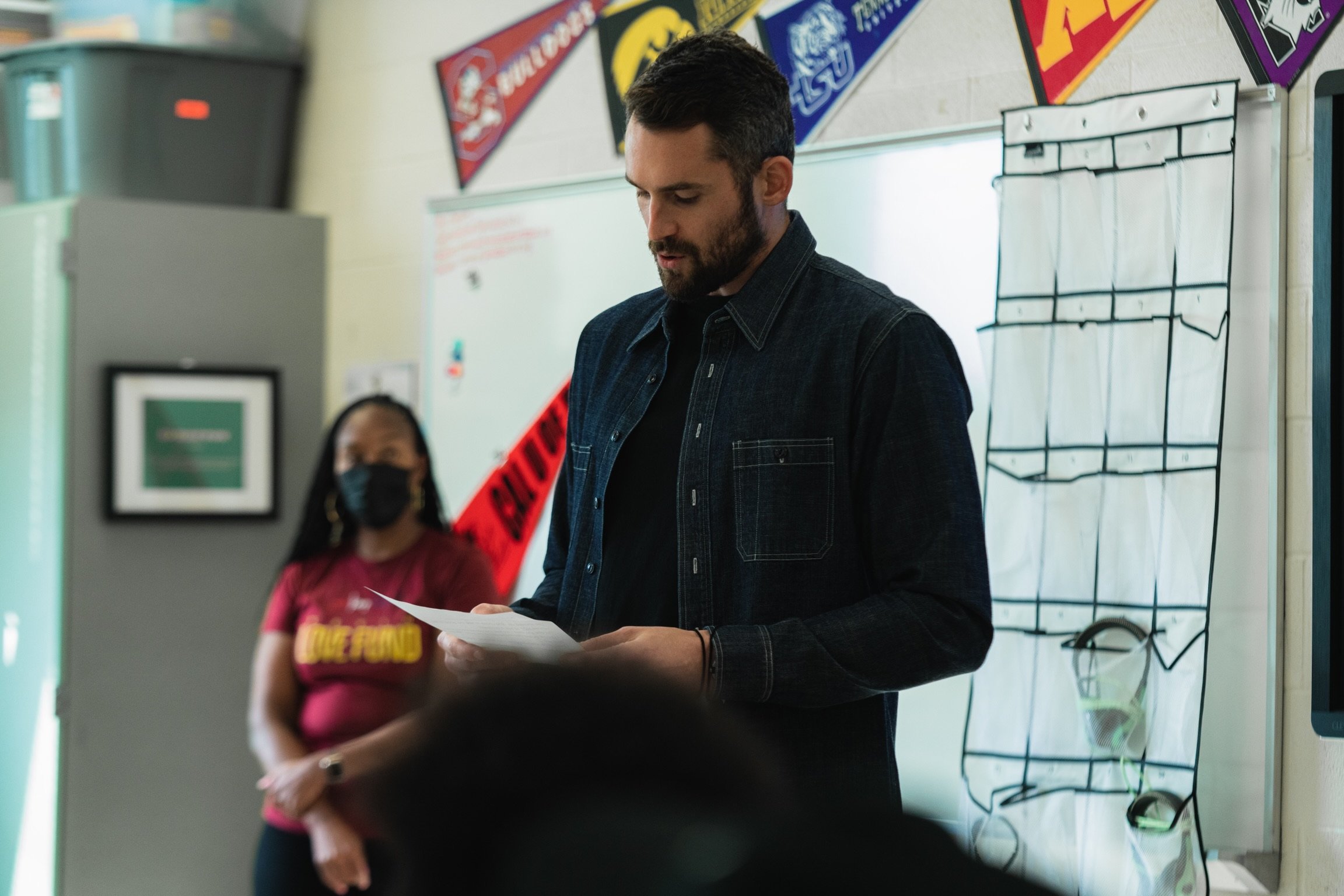

Octavio Martinez, the foundation’s executive director, started thinking about changing the foundation’s strategic focus as the funder headed into its 75th anniversary. “It really put me on the path of thinking, ‘Well, what about the next 10 years? What are we going to be at the 85th, 90th or even farther?’” he said.

“It led me to think that it’s time for the Hogg Foundation to gather all of these new sort of approaches and tools to really start to address health equity and to achieve overall well-being,” Martinez said. “To me, to really get to that, we need to start shifting our focus more upstream.”

The shift upstream is commonplace among public health funders these days. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation started the trend more than a decade ago. Public health funders big and small followed suit.

It’s more unusual to see a mental health foundation take the upstream track, if for no other reason than the dearth of foundations really dedicated to mental health. Although as public health funders search for the root causes of physical ailments, their work overlaps more with what might traditionally be considered the purview of mental health funders. RWJF, for one, supports work addressing social isolation and childhood trauma.

The Hogg Foundation's move upstream underscores the potential for even more overlap. It turns out many of the things that affect long-term physical health—think housing, transportation, poverty, the built environment or employment—also contribute to mental well-being.

“When the social determinants are not addressed, they contribute to overall poor health and invariably also contribute to either the potential to create mental illness or exacerbate the symptoms and illnesses that folks are already having to deal with,” Martinez said.

Martinez uses housing as an example of the interconnectedness of mental health and social determinants. Many homeless are also dealing with poor mental health, he says, whether that’s PTSD, substance abuse problems or schizophrenia.

“When you work on homelessness, you’re in the mental health arena, even if you don’t realize it,” he said. Without addressing one, it’s difficult to make progress on the other.

For this set of grants, each county will decide which underlying factors it wants to address. The overall focus should be greater mental health equity, which will mean bringing a lot of often overlooked groups to the table.

“We’re asking all of our communities to look at their whole community, their entire population, really identifying who’s not been at the table, who’s been left out, who’s been marginalized,” Martinez said. The hope is that a more equitable planning process will foster more equitable outcomes when it comes to community mental health.

Disparities in mental health are a real problem. Racial and ethnic minorities tend to have worse mental health and a harder time accessing care, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. Economic status also affected access to mental health and substance abuse services, the organization found.

The World Health Organization found that women and low-income people were more likely to have poor mental health, along with those who reported weak social support. Disparities were visible in children, and disadvantages tend to compound over time, the report said.

Martinez knows that building trust with those communities will take time, which is why the grants are intended to be three-year planning grants.

“We’re not expecting them to have solved anything yet," he said. “We do hope that at the end of the three years, we’re ready to then implement and fund some activities that start to get at some of these very specific issues.”

Equity was actually a big reason that some of the first grants under the new strategy supported rural communities. When Hogg overhauled its strategy, Martinez noticed that most of the work supported by the foundation during his tenure was in urban areas, even though proposal requests were open to anyone.

“It just turns out that academic, urban or very well-seasoned nonprofits have capacity to write grants or to coalesce an idea into something that could be put into a proposal,” he said. “That wasn’t coming from rural Texas.”

It’s a challenge common to many foundations that work in rural regions. Local nonprofits rarely have the same capacity as big urban organizations funders are used to partnering with. That often means that the funder ends up devoting resources to build that capacity. In this case, Hogg is supporting a sixth grantee, Alliance for Greater Works that will provide technical assistance and help with coordinating the other five grantees.

Without the local capacity in place, it’s easy for rural communities to be overlooked. “Rural communities aren’t getting equal access to resources,” Martinez said. In Texas, that means about 4 million people stuck in the foundation’s blind spot. It’s an oversight that this set of grants hopes to address.

Related: