He Was a Young Hedge Funder with a Lucrative Job. Now He’s Working to Scale Access to Healthy Food

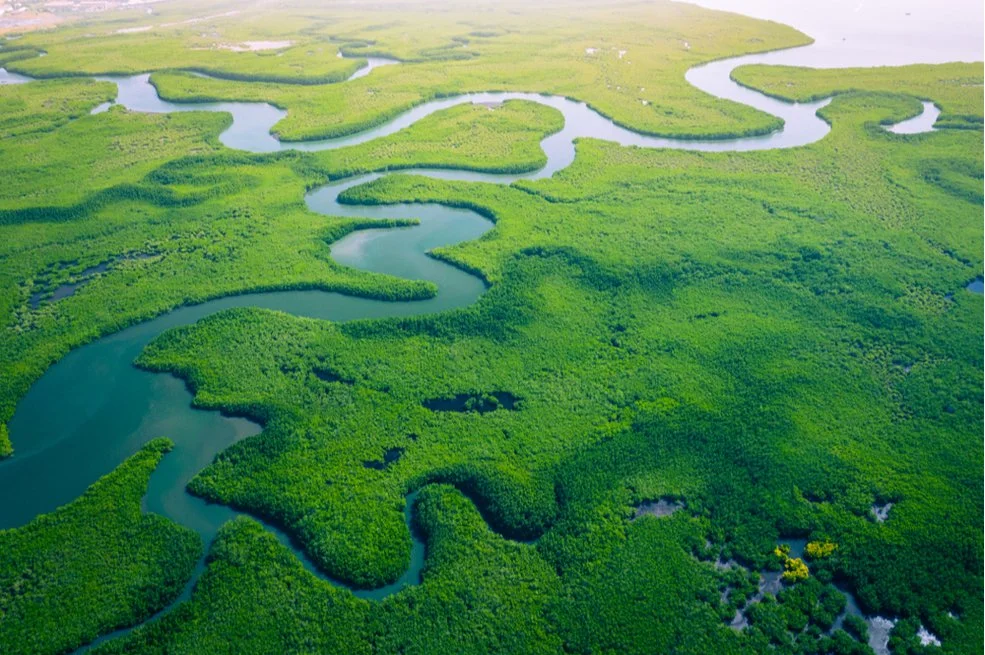

/An Everytable outlet in LA.

Los Angeles native Sam Polk headed east to attend Columbia University, graduating in 2002. He was a bond and CDS trader with Bank of America, and went on to work for King Street Capital Management. Then, at just 30 years old, Polk walked away from his lucrative trading job at a hedge fund and entered the nonprofit and social change arena.

As we’ve reported, many individual donors are turning to philanthropy earlier than ever before, balancing business with other interests, or in some cases, leaving business altogether. Energy trader John Arnold and his wife Laura have been major givers since their 30s, when John shuttered Centaurus Advisors and retired from the hedge fund world. Young tech leaders like Mark Zuckerberg have also embarked on major giving early in their careers.

Polk is no billionaire. However, since returning to Los Angeles, he’s launched a nonprofit called FEAST (formerly Groceryships), spinning it off into the for-profit Everytable, a grab-and-go restaurant that offers healthy, made-from-scratch meals across seven locations in Los Angeles—with an eighth location to open soon in Watts. Not long ago, Everytable received its first program-related investment from the Kellogg Foundation, a funder with a keen interest in expanding access to healthy food. Recently, I spoke with Sam Polk to learn more about his journey from finance to philanthropy, and about the organizations he founded.

Polk began by describing the forces that made him leave the world of finance—at a time when, presumably, things were just getting started for him. “I was a senior trader at one of the largest hedge funds in the world. And then I basically just sort of looked around and realized I don’t want to be spending my life chasing more and more stuff for myself.”

At the time, Polk was reading a lot of Taylor Branch, the great chronicler of Martin Luther King Jr., and learning more about the Freedom Riders. “I was reading about them going into places like Birmingham, and I started to realize that while that was going on, there were also people trading bonds… I wanted to be on the other side of that.”

On the heels of this change of heart, Polk quit his Wall Street job in 2010 and returned to his native Los Angeles. He spent the next few years writing a book and doing volunteer work in Los Angeles through organizations like My Friend’s Place and Aviva. He started moving into the food justice arena after watching a number of Netflix documentaries about food deserts. He realized that some of these deserts were in neighborhoods not too far away, like Compton and Watts, where he says life expectancy can be up to 10 years less than that of wealthy neighborhoods like Bel Air.

In 2013, Polk started a nonprofit called Groceryships (now FEAST) with his wife Kirsten Thompson, a psychiatrist, with the aim of addressing the food and health disparities affecting families throughout the U.S. But Polk, who still serves as a director of FEAST, wasn’t exactly satisfied with his formative experiences in the nonprofit arena. In fact, he once penned an article for the Los Angeles Times titled “I left finance because I wanted to make a difference. Nonprofit work never did the trick.”

"I found the joy of service overshadowed by the exasperation of trying to keep a not-for-profit organization afloat,” he wrote.

Now, Polk says, “I think the most impactful entrepreneurs are nonprofit leaders, but there’s a graveyard between nonprofits that get started and those that are sustainable and impactful organizations. So much time and effort goes into getting funding from foundations, running events, it’s so hard to squeeze juice out of that stone, and because nonprofits start from zero every year, it’s sort of hard to grow something sustainable.”

In that article, Polk also noted that of the more than 200,000 nonprofits founded in the U.S. since 1970, fewer than 150 have achieved $50 million in annual revenue. Compare that to the for-profit world, where 125 to 150 U.S. companies founded each year reach $100 million in annual revenue.

Polk does believe that charities are critical and essential, particularly in doing work that has no revenue potential, such as feeding and housing the homeless. But through his experiences, he also believes that social enterprises have a key role to play, and can inject disruption and innovation into the nonprofit sector. “Social enterprise can combine the heart of a nonprofit with the scalability and innovative potential of for-profits.”

Polk connected with Father Greg Boyle, an American Roman Catholic priest and founder and director of Homeboy Industries, a legendary L.A. organization that provides former gang members and the recently incarcerated with a variety of programs such as mental health counseling, tattoo removal and employment services. Homeboy Industries has grown from a single bakery to almost a dozen social enterprises. Polk was inspired by this model, and with the encouragement of Father Boyle, started work on Everytable in 2015.

Because of his experiences through FEAST, Polk already knew a lot about the landscape. And he was convinced that there was a huge demand for healthy food. “There’s a misconception that folks in underserved communities like fast food more than anything. The truth is, what they like is $5 meals that are convenient and fast. We started to understand that if you could make a business that was able to sell meals at $5 that were healthy, there would be a huge demand for it.”

A central part of the success of affordable food is scale. McDonald’s is able to keep prices low because, as Polk says, “they have the most efficient and immense supply chain in the world.” Everytable, meanwhile, keeps things cheap with centralized production and small-footprint stores. Polk initially planned to price meals at $7 or $8 in affluent neighborhoods like Santa Monica, and price them at $5 in poorer neighborhoods. His expectation was that they’d break even in places south of Interstate 10 and generate revenue in places like Santa Monica. In reality, Everytable’s locations in underserved communities are its most profitable stores.

The investment from the Kellogg Foundation will support Everytable in education and programming around food justice at Cal State University, Los Angeles (where Everytable has a store), help implement the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at its stores, as well as introduce its franchisee program, designed for entrepreneurs of color.

Polk was able to make this key connection to Kellogg in part because of Daniel Tellalian, a managing partner of Avivar Capital, who was the co-designer and lead for deployment of the California FreshWorks Fund, the nation’s largest healthy food financing initiative. Tellalian and Polk both serve on the board of the Los Angeles Food Policy Council.

“It’s been a great partnership,” Polk said about Kellogg’s backing. “It’s our first PRI. These things take a long time to get and don’t happen that often.” Because of this first one, though, Everytable is now in talks with some major Los Angeles foundations to add to that investment, Polk explains. And he’s becoming less disillusioned with foundations, as well, adding that “Kellogg Foundation have been incredible supporters for us.”

Polk is pretty high on PRIs, and talks about the need for foundations to do more on this front. “Foundations give away as much money every year as the entire venture capital community invests into companies. The potential for them to support systems changing organizations is huge, and I think PRIs are the most powerful lever in that potential.”

In fact, Kellogg’s backing for Everytable—assuming it pays off over the long term—offers a great case study of the critical role that PRIs and impact investments can play in advancing the priorities of foundations. While many funders have swung behind the goal of expanding access to healthy food in underserved communities, this is a vast challenge that’s beyond the scope of traditional grantmaking. Without for-profit models that can really scale to bring better food options into low-income communities, millions of Americans are likely to continue to live in food deserts.

As for what’s down the line for Everytable, Polk is definitely thinking big, looking to change the entire food system of Los Angeles. “We think we can have hundreds of stores in L.A. We also do subscription delivery business. If you’re living in Compton, you can get fresh, delicious meals delivered to your doorstep.”

In the future, Polk hopes Everytable will go national with thousands of locations.