On the Radar: Inside a Push to Hook up Progressive Donors and Grassroots Voter Groups

/MattGush/shutterstock

Voter engagement has been on the agendas of a number of dedicated funders for decades. But the 2016 election created a far greater sense of urgency among social justice philanthropists, along with the potential for more support to a politicized niche most funders tread carefully around. Encouraging civic engagement among likely Democratic voters has been one aspect of a “Trump bump” in progressive grantmaking, drawing interest from foundations and individual donors alike.

Take Susan and Nicholas Pritzker, who have access to a fortune topping $1 billion and a serious interest in deploying those assets to benefit grassroots movement groups. “What became crystal clear to me in the aftermath of 2016,” Susan said, “was how really badly broken many of the mechanisms of our political system had become, and how many people were being left out of the process or were opting out, because they didn't feel it would do any good.”

The Pritzkers are just one example. Since 2016, voter engagement has become a greater priority for plenty of funders, from liberal legacy foundations like Ford and Kresge to newer players that aren’t as shy about bridging the uncomfortable (c)(3)-(c)(4) divide. So why is it, then, that so many local movement organizations still operate on shoestring budgets and can’t properly sustain their operations, especially between election years?

The simple answer is that most of the groups engaging voters on the ground just aren’t on the radars of wealthy liberal donors. Why would they be? Many of those organizations are new, formed in communities few of America’s upper class call home. And their leaders tend to have sparse connections to elite business and philanthropy, a world that they may, justifiably, view with suspicion.

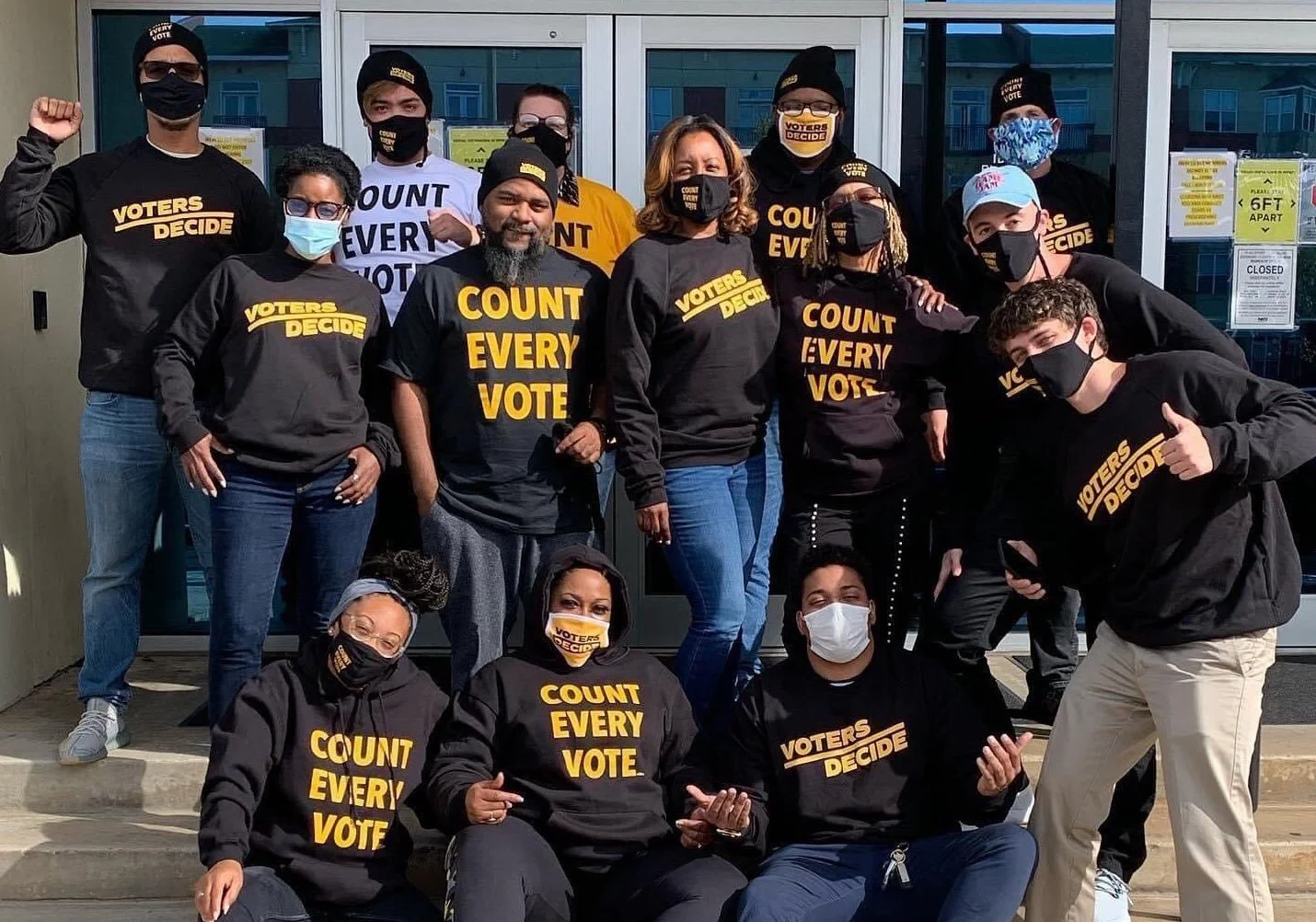

But they need money, and folks like the Pritzkers have it in spades. The mission of the Movement Voter Project (MVP) is to bridge that divide—and to also draw in support from donors of more modest means. Operating at the nexus between wealth and local community organizations, MVP has moved over $15 million to hundreds of movement groups. It’s played a key role getting ground-level activist campaigns up to speed, including Black Voters Matter, the grassroots civic engagement project that helped ensure Doug Jones’ 2017 victory in Alabama’s special senatorial election. MVP has also seeded over 30 new groups getting out the vote in swing states and districts.

Related:

Inside the Libra Foundation: How a Branch of the Pritzker Family Backs Movement Building

Fight on All Fronts: A Progressive Group Looks to Build Political Power

Propelling Change: A Venture Philanthropy Shop Gets Behind Progressive Organizing

Bridging the Donor-Organizer Knowledge Gap

As founder and executive director Billy Wimsatt tells it, this dynamic organization got its start as a humble Google Doc. In 2014, Wimsatt was working on project called Vote Mob, which provides young people with training and stipends to carry out electoral organizing in key states. “A lot of people in progressive donor communities were thankful we were turning out young voters,” he said. “They asked us: Are there any other groups there we should be funding?”

A veteran movement organizer and social entrepreneur, Wimsatt co-founded a variety of initiatives including Solidaire, Rebuild the Dream and the League of Young Voters. To address the donors’ question, Wimsatt and his colleagues drew on insider knowledge and relationships to create an informal list of good local movement groups in need of cash. The list made its rounds, and in the end, funders moved over $400,000 to those groups. “We realized this was a gap in people’s knowledge,” Wimsatt said. “A lot of donors and foundations mostly give to national groups or state groups, and that’s a problem. You shouldn’t need a huge staff or even belong to a donor community to get access to this information.”

Inspired by that initial success, Wimsatt turned the list into a website, which grew into an entire organization advising donors on funding local voter engagement and community organizing. Today, MVP’s tools include a database of effective movement groups in need of support, as well as curated funds for donors who want to back specific political goals or issues. There’s also a sizable team that “acts as a free, high-level program staff for people who want to move money in a customized way,” Wimsatt said.

MVP’s impact is on the rise. In 2016, it helped move $2.5 million to local groups. Last year, Wimsatt and team exceeded their goal of $10 million, moving over $14 million in donations. This cycle, the goal is $50 million to $100 million, which would be a substantial influx for organizations accustomed to doing a lot with a little. Most of that money comprises direct donations, with MVP playing an advisory role, often working hand-in-hand with donors. MVP does not usually make donations in its own right, but the gifts it recommends go to 501(c)(4)s and PACs as well as 501(c)(3)s. This stream of cash is yet another example of the increasingly blurred line between tax-deductible philanthropy and political giving, with more funding groups and nonprofits alike operating on both sides of the divide.

Reactive to Proactive Giving

Like too much philanthropy, political fundraising tends to be reactive and cyclical. People get bombarded with emails and calls from candidates during election season, but that’s all for temporary campaign infrastructure. As groups like the Funders’ Committee for Civic Participation (FCCP) have argued, a more effective funding model for voter engagement would provide support during electoral off-years, paying ample attention to smaller races. Wimsatt agrees. “We want to help donors go from supporting high-level national infrastructure to getting money to communities on the front line,” he said.

To make the most of donors’ finite resources, MVP prioritizes states and jurisdictions where movement funding is lacking, and where newly engaged voters can make a difference in multiple races. “By focusing 100 percent on voter turnout, we impact races up and down the ballot, not just the marquee congressional and presidential races,” said David Mendels, a former tech executive and donor to MVP.

MVP’s roster is varied by design. There’s a set of groups that are “like blue chip stocks” for donors who prefer more established options with substantial track records, Wimsatt said. And then there are smaller groups, including organizations deeply embedded in particular places, or those still new to voter engagement. MVP also places a premium on emergent organizations led by organizers who can engage new communities. “Most movement groups are fairly small and local. The ones that matter most for elections are in swing districts and states. So they don't have easy access to all the potential donors in blue states,” Mendels said.

Along with Mendels, Susan Pritzker is a frequent supporter of MVP, which derives most of its own funding from individual donors who appreciate the service it provides. Pritzker, who funds MVP herself and through the Libra Foundation, is optimistic despite her dim late-2016 assessment of American democracy’s inclusivity. “The outrage isn't flagging, and folks seem energized and eager to participate,” she said. “Though the concept of funding politics in this manner may not be comfortable or familiar for the rank and file Democratic donors of the baby boomer generation, it seems to resonate with younger people.”

Going forward, MVP wants to capitalize on that energy by building up infrastructure in swing states like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Florida, Arizona and Wisconsin—the last of which stands in particular need of investment. MVP is also decentralizing and expanding its own model toward a greater sense of personal connection with donors. Wimsatt is working toward a goal of 15 to 20 local teams capable of one-on-one dialogue with clients. As that effort progresses, MVP appears to be meeting its fundraising goals: In the first quarter of 2019, it has already recommended over $8 million in pledges, more than half of the total it raised for the entire 2018 cycle.

While advocates like Wimsatt emphasize the importance of off-year support, voter engagement funding still tends to be cyclical. As the 2020 race heats up, we’re likely to see a ramp-up of interest in places like MVP, especially from social justice donors encouraged by Democrats’ decent performance in 2018. MVP’s focus on organizing individual donors also complements other progressive voter engagement entities like NEO Philanthropy’s State Infrastructure Fund, which derives most of its support from foundations.

Of course—and it’s a point we make often—there are downsides to letting ideologically-motivated members of the far upper class wield even greater influence over the public square. And while they’re often quite progressive (and anti-Trump) on social issues, many mega-donors shy away from economic causes like the labor movement and Wall Street regulation.

Also, while efforts like MVP can catalyze gains for a wider variety of progressive causes down the line, it’s important to remember that wealthy donors on the right also invest heavily in voter mobilization—and voter suppression—efforts.

Related: