As the COVID Fight Continues, Who’s Funding Surveillance for the Next Biological Threat?

/Sebestyen Balint/shutterstock

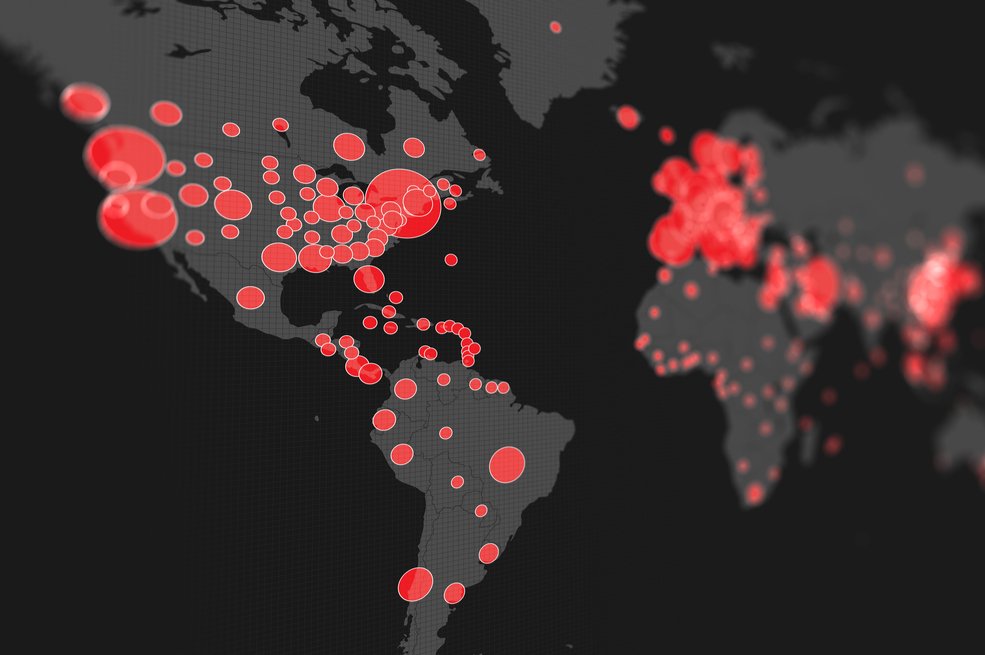

Where were the tripwires to alert the world when COVID-19 first started spreading? And why didn’t the alarms that did sound trigger a coordinated effort that could’ve helped stop a disease from becoming a full-blown pandemic?

No country has escaped the coronavirus, and surges continue to roll across continents. Now, as the number of confirmed deaths has ticked past 5 million globally, and a staggering 249 billion cases have been recorded around the world, the hope is that COVID-19 will mark a tipping point on global preparedness.

Of course, the problem’s not all about one pathogen. The COVID response follows a pattern of parochialism that’s occurred with other outbreaks like SARS in 2002 and Ebola in 2014—followed by relieved complacency when the heat dialed down. Still, biosecurity remains largely a function of government security, and has drawn scant support from philanthropy.

Here’s how a few notable exceptions like the Rockefeller Foundation, Open Philanthropy and Skoll are backing the early warning systems of the future, amid calls for greater collaboration.

Rockefeller’s “next chapter”

The Rockefeller Foundation has long believed that early detection is essential to preventing the pandemics of the future.

In a move it says marks “the next chapter” in its 100-year history of applying science and technology to pivotal issues of public health, Rockefeller recently committed up to $150 million to create a Pandemic Prevention Institute (PPI) to help the world detect, mitigate and prevent pandemics. PPI funding fits within one of Rockefeller’s five overarching focus areas, achieving health for all, and aligns with a specific commitment of $1 billion over three years to catalyze a pandemic recovery that’s both equitable and green.

Tackling disease isn’t new for Rockefeller. From its earliest days, the foundation has helped shape the modern field of public health and been a leader in fighting everything from the 1918 flu pandemic to hookworm, yellow fever, polio and AIDS. The foundation’s pioneering detection work began in 1999, and built up to its Disease Surveillance Networks Initiative that launched in 2007 and concluded in 2012, when Rockefeller determined the program had met its objectives.

From the time COVID-19 first spread in early 2020, the foundation knit together broad constituencies to formulate a national testing and tracing action plan in the U.S. that later included scaling for schools and emergency measures.

As reported in Inside Philanthropy, the foundation reenergized its surveillance work on a global level in July, when it committed an initial $20 million in funding and non-financial collaborations to establish the Pandemic Prevention Institute (PPI).

PPI is a global network that partners across public, private and academic sectors to build an early warning system. It employs developing technology that sees and shares the signs of potential outbreak—rather than the raw data itself—to ensure data privacy and integrity.

Dr. Rick Bright, CEO of PPI and senior vice president of Pandemic Prevention and Response at the Rockefeller Foundation, noted the importance of using a federated model. “With COVID-19, we saw firsthand how failures of trust fanned the flames of the pandemic,” he said. Information wasn’t being shared by governments at a global level as contributors worried that proprietary information like genomic sequences would be “used by others for profit or publication without attribution, acknowledgement or benefit.”

In response, the institute is developing a model that will allow the individuals and groups that own and generate data to continue ownership “at the most granular level.” Bright said it has no intention of becoming “a central hub of global data,” and instead “keeps data more secure because it leaves the data sets for local use.”

Along with agencies that have been instrumental to the current COVID response, like the World Health Organization’s Hub for Pandemic and Epidemic Intelligence in Berlin and the U.K.’s Global Pandemic Radar, the PPI counts nearly 30 global partners, including educational institutions like UC Berkeley, investigative networks like Thailand’s CONI Alliance, and companies like the global health strategy firm Rabin Martin.

Wellcome Trust is partnering with PPI on a data.org initiative that Director Jeremy Farrar characterized as an “exciting example of the kind of innovative approaches that are needed.” PPI has also collaborated with the global alliance for diagnostics, FIND, to develop a next-generation genomic sequencing capacities map that will identify disparities and gaps in genomic tracking.

In its first six months, PPI has amped its number of staff to nearly 20, and spent more than $25 million to plug holes in global data collection and sharing, and claims a demonstrated improvement in the speed and scope of data collection and sequencing in the U.S., Africa and India.

An important role to play

Grantmaker Open Philanthropy believes private funding may have an important role to play in pandemic prevention that is distinct from the role of government. It makes more than $50 million in grants annually in four focus areas: Global Health and Development, U.S. Policy, Global Catastrophic Risks and Scientific Research.

The foundation has been funding in the biosecurity field since 2015, and made Global Catastrophic Risk a focus area in 2017, zeroing in on two threats: biosecurity and pandemic preparedness and the risk potential of artificial intelligence.

Primarily backed by Cari Tuna and Dustin Moskovitz, a co-founder of Facebook and Asana, Open Philanthropy’s biosecurity and preparedness work focuses on three primary areas: biosurveillance, governing dual-use research (research that could be used for positive or negative ends), and policy development. The foundation has committed more than $101 million in funding to the issue thus far, excluding grants and investments made out of a separate science portfolio that supports related biotech initiatives like Binx, Icosavax and Sherlock.

Open Philanthropy made its largest grant within the category in 2019, a $19.5 million gift over three years to support Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security (CHS)’s general work, and a specific initiative to support emerging biosecurity leaders. That funding built on a three-year, $16 million grant made to CHS in 2017 to support ongoing biosecurity and global health efforts and catastrophic risk assessment.

More recent grants include an August commitment of $3.3 million over three years to Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) to support a project investigating dual-use research in the biosciences; and $1 million in March to the MIT Media Lab to support the biosecurity research of Professor Kevin Esvelt.

As COVID continues to pose “exactly the kind of threat our grantees have been warning about,” Moskovitz also discussed a broad spectrum of other COVID response work in this thread.

Skoll anticipates the threat

One philanthropist recognized the global risks of pandemics more than a decade ago. Social entrepreneur Jeff Skoll made it one of the first five goals of a $100 million Global Threats Fund he founded in 2009. When funding was strategically sunsetted in 2017, the pandemic portfolio was spun off into a new standalone, Ending Pandemics.

Funded by the Skoll Foundation, the initiative works to expand epidemic intelligence to help the world identify hotspots and stop outbreaks at their source. Some of its earliest investments went to early warning systems like the CORDS Network, GIDEON, and The Sentinel.

Skoll’s current COVID response builds on the foundation’s first efforts in April of 2020, which deployed $100 million along two strategies concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiological tools and respiratory equipment. In September 2021, Skoll upped its commitment to pandemic mitigation by $100 million over five years, a total number that may collectively rise to $500 million across the organizations.

Funding is also supporting the coordinated response and prevention efforts championed at President Joe Biden’s Global COVID-19 Summit, a cross-sector meeting of more than 100 representatives of government, the private sector and philanthropy that took place on the sidelines of the U.N. General Assembly.

Skoll CEO Don Gips says philanthropy has a role to play as “society’s risk capital” and is committed to working with government to do “what philanthropy does best… take risks, support civil society voices, and test out solutions” that governments can ultimately assume. Like other leaders, he’s resolved to unite across sectors in the common cause of preparedness, despite all challenges.

Calls for collaboration

The Rockefeller Foundation also recognizes that collaboration is key. The PPI is seeking new partners through the RF Catalytic Capital, Inc. (RFCC), a charitable offshoot of the foundation created in 2020 to help like-minded funders from all sectors to combine resources to find and scale social impact solutions. Now incubating the PPI, the RFCC will eventually launch it as a standalone.

Funders from across the spectrum will have to muster new resolve to meet the future. Explaining its investment in the institute, Rockefeller President Dr. Rajiv J. Shah said, “After too many pandemics, the world has said ‘never again’ only to miss the moment—and the chance—to prevent the next one.”

“At the Rockefeller Foundation,” he continued, “we believe it’s now possible to say ‘never again’ and mean it.”