Is MacKenzie Scott the Leading Social Justice Funder? Yes and No

/Andrey_Popov/shutterstock

This article was originally published on April 11, 2023.

When MacKenzie Scott started distributing billions of charitable dollars in 2020, the impressively large infusions of general operating support she moved to prominent social justice organizations generated accolades from many grassroots leaders. Scott’s historic philanthropy brought with it the promise of a new model of giving that could actually shift power away from billionaires and toward people closest to the injustices of the world.

Scott was sending extraordinarily large gifts to groups like the Movement for Black Lives, Latino Justice PRLDEF, International Trans Fund, One Fair Wage, Astrea Lesbian Foundation for Justice and The Opportunity Agenda. They were often by far the largest dollar amounts such groups had ever seen, and the lack of restrictions signaled a form of trust in recipients that professional philanthropy has rarely modeled.

As a result, media coverage of Scott’s giving has sometimes implied that she is now a leading funder of social justice work. In one sense, that descriptor is hard to dispute. After all, Yield Giving, as her philanthropic initiative is now named, is moving a massive amount of money to groups that are working on what many would describe as social justice work. In fact, in terms of sheer dollars, she may indeed be directing more dollars to justice work than any other institution or major donor today — maybe ever. Combine that with the fact that her dollars are mostly given as general operating support, and you can make a compelling case that Scott is setting a high watermark for philanthropy that shifts power.

But now that we’re a few years into the endeavor and we have a sizable amount of data to dig into, it’s worth asking — should we be thinking of MacKenzie Scott predominantly as a social justice funder? Is most of her money going to work that centers marginalized people in efforts to fundamentally change unjust systems?

Answering that question gets tricky for a couple of reasons. First, it requires us to take into account a truly staggering number of grants — over 1,600 recipients for $14 billion. MacKenzie Scott’s gifts are often disproportionately large compared to the typical grants in any particular field she’s backing, but they may actually be a pretty small slice of the pie of her overall giving. Climate change is a prime example: It’s a relatively small portion of her philanthropy, but nonetheless, her huge grants stand out in an underresourced field.

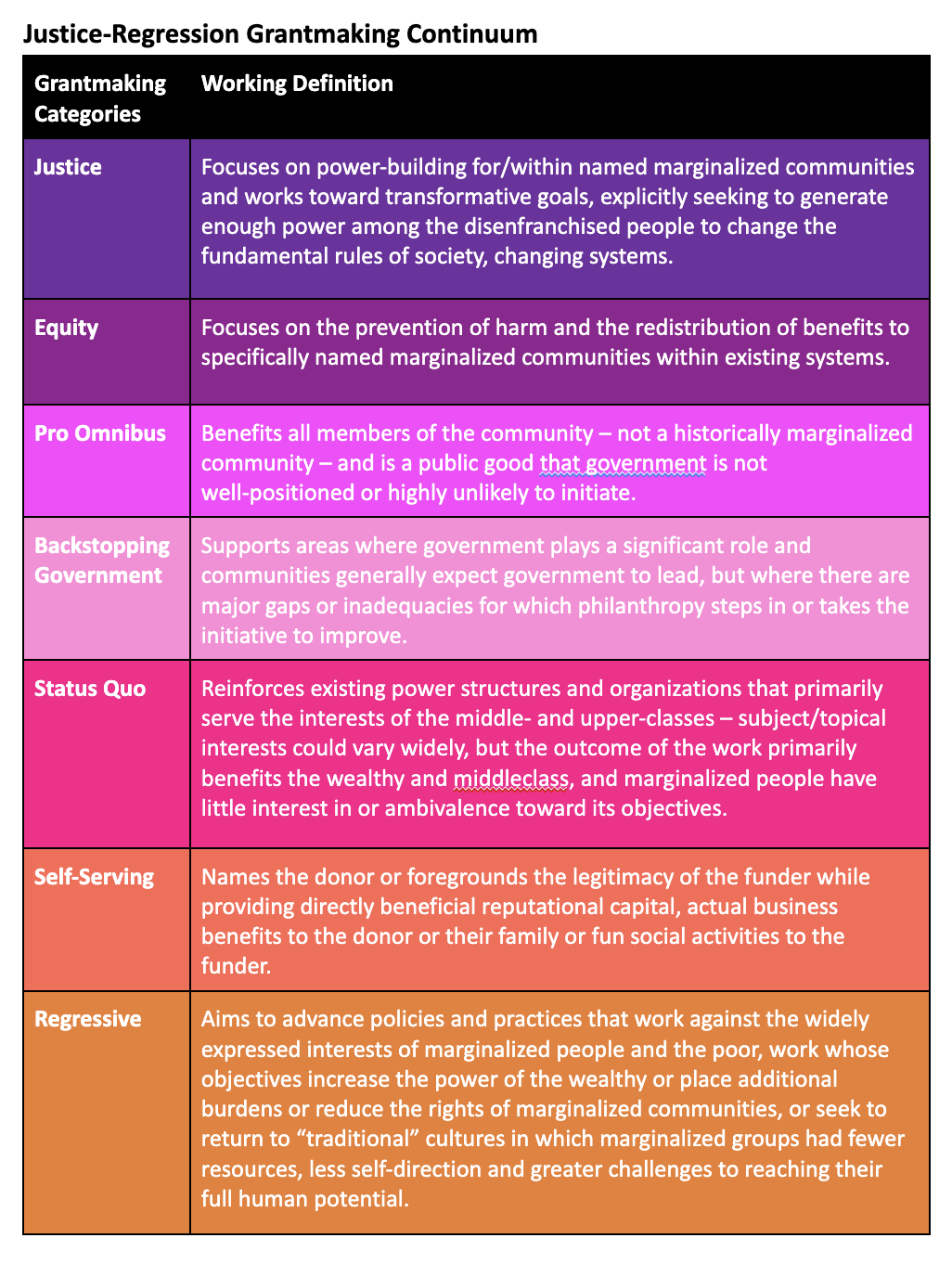

But we also have to contend with another difficult question — what, exactly, is social justice giving, anyway? Figuring this out is the goal of a research project I embarked on about a year ago, which produced the justice-regression grantmaking continuum. The project proposes a framework built around an increasingly common definition of justice work within the nonprofit community: that which focuses on power-building for or within named marginalized communities and works toward transformative goals, explicitly seeking to generate enough power among the disenfranchised people to change the fundamental rules of society, changing systems.

This definition has roots in the “Mismatched” report of the Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE). Using the larger continuum IP has developed, we can assess a giving portfolio and assign grants to the justice category or a range of other categories, including equity (also based on PRE’s definition), pro omnibus, backstopping government, status quo, self-serving, and regressive.

When Yield Giving released its database of grants last year, we began to wonder how its giving would stack up along that continuum, so we gave it a shot, starting with a strategic sampling of 20 grants.

While it’s admittedly limited, it proved to be a useful exercise both in developing a stronger understanding of what social justice funding really is, and of Scott’s main philanthropic priorities. The result is a picture of a mega donor for whom social justice and shifting structural power is certainly one element, but not the predominant theme, as Scott and her team shower a sprawling range of organizations with funding.

Examining 20 grants to start the conversation

In December 2022, Scott made public on her new Yield Giving website a database of all the grants she made from 2020–2022, a total of 1,605 grants ranging from $75 million to $300,000, and 450 grants for “undisclosed” amounts, respecting the wishes of the grantees themselves.

Ideally, an academic institution or research organization like the Center for Effective Philanthropy, which has begun studying Scott’s giving, would use the justice-regression grantmaking continuum to analyze all 1,605 grants and provide a more definitive analysis, but we decided it would be worth examining a sampling of grants to form a hypothesis.

First, we looked at the 10 largest grants. After all, that’s really putting your money where your mouth is, right? For the second half, we took a random sample using a random number generator to choose from the remaining 1,595 lines of data.

This examination of Scott’s giving was also a bit of an experiment to test whether different people using the same set of definitions would locate individual grants on the same place on the continuum laid out in IP’s State of American Philanthropy research report “Philanthropy, Social Justice and Shifting Power.” (You can also see the full criteria presented in the graphic above.)

I rated the grants myself, using the mission statement of the organization and a description of how they are carrying out their work, using their website as a guide. I also enlisted two other reviewers. One is a philanthropy professional who has worked in executive positions for several high-profile family foundations and for philanthropy-serving organizations, and is now an executive in a consulting practice. The other reviewer is a recently retired political science professor who, a decade ago, cofounded a small, grassroots nonprofit and had some success soliciting grants from a variety of funders.

As you’ll see, these ratings are subjective, and there was a fair amount of disagreement, a reminder that it’s not always easy to draw clear borders around nonprofits’ work. Some of the organizations themselves may disagree with where we landed, but none of these categorizations should be considered a slight — there’s a wide array of important work being done here, and there were no grantees on the list that could be placed in the “self-serving” or “regressive” categories. Our goal was simply to identify the grantees chiefly working on systems change. Here’s what we came up with.

Among the 10 recipients receiving the largest grants, we categorized two as doing justice work

1. Co-Impact Gender Fund — Scott’s largest grant to date was $75 million in 2021 to this group, and she gave Co-Impact $50 million in 2020 for general operating support. In its own words, “Co-Impact is a global philanthropic collaborative focused on improving the lives of millions of people through just and inclusive systems change.” I found that the Gender Fund’s work matches the definition of justice work, and my poli-sci professor’s assessment was the same, but our philanthropy professional felt it fit the definition of equity work — that which focuses on the prevention of harm and the redistribution of benefits to specifically named marginalized communities within existing systems.

Majority Justice: 2 justice, 1 equity

2. GiveDirectly’s Project 100+ — Scott’s second-largest grant directed $1,000 grants to randomly selected households that applied for COVID relief. In its regular work, GiveDirectly provides direct cash transfers to people living in poverty in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Liberia and other countries. I categorized this work as government backstopping — grantmaking that supports areas where government plays a significant role, but where there are major gaps or inadequacies. My philanthropy professional assessed this one as pro omnibus grantmaking — work that benefits all members of the community, not a historically marginalized community. And my poli-sci professor thought this one fit the definition of equity grantmaking.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 1 gov back, 1 pro omnibus, 1 equity

3. Amref Health Africa — This group’s stated mission is “Lasting health change in Africa through community-led, people-centered primary health systems while addressing equity and social determinants of health focusing on women and girls as agents of change.” I came to the conclusion that within its country contexts, the work was generally pro omnibus, with some arguable elements of equity and government backstopping. My other reviewers, relying only on the mission language supplied by the organization, both located the work in the justice category.

Majority, Justice: 2 justice, 1 pro omnibus

4. Hispanic Scholarship Fund — HSF’s mission is “to empower students and parents with the knowledge and resources to successfully complete a higher education, while providing support services and scholarships to as many exceptional students, HSF Scholars, and alumni as possible.” I perceived this to be a classic example of equity work because it is directing resources to a marginalized group, but not trying to fundamentally alter the systems of society. Interestingly, my philanthropy professional put this in the justice category and my poli-sci professor considered it government backstopping.

Majority, Not Justice: 1 equity, 1 justice, 1 gov back

5. RIP Medical Debt — “Our mission is to end medical debt and be a source of justice in an unjust healthcare finance system, a unique solution for patient-centered healthcare providers, and a moral force for systemic change.” Despite the justice-oriented packaging, my review of its website concluded that it is engaging in government backstopping, with only a tiny amount of systems-change advocacy. My philanthropy professional described it as pro omnibus work, and my poli-sci professor put it in the equity category.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 1 gov back, 1 pro omnibus, 1 equity

6. Planned Parenthood Federation of America — Scott gave $50 million to the national office, but she has also given huge gifts to at least 21 local Planned Parenthood operations. Planned Parenthood’s mission is “to ensure all people have access to the care and resources they need to make informed decisions about their bodies, their lives and their futures. Planned Parenthood is a trusted healthcare provider, educator and passionate advocate in the U.S., as well as a strong partner to health and rights organizations around the world.” My perspective is clear that these are essential health services that should be provided by our normal healthcare system, making this grant government backstopping. My poli-sci professor agreed. But my philanthropic professional considers this equity work, and I can understand the argument for that, given that these services aim for equal healthcare for a particularly vulnerable population. This was a tough (and likely controversial) one, but the reviewers came down on the majority of the work being service provision.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 gov back, 1 equity

7. Partners in Health — Partners in Health’s mission is “to provide a preferential option for the poor in healthcare by bringing the benefits of modern medical science to those most in need of them and serving as an antidote to despair.” It operates in Latin America and the Caribbean; the Middle East and North Africa; and sub-Saharan Africa. PIH has lots of language on its website talking about healthcare justice, but does not seem to be engaging marginalized populations in fundamentally changing healthcare systems in their countries, so I tagged this as government backstopping and my poli-sci professor agreed. My philanthropy professional put this in the pro omnibus category.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 gov back, 1 pro omnibus

8. Prairie View A&M University — It describes itself as “a state-assisted, public, comprehensive land grant institution of higher education. It is dedicated to achieving excellence and relevance in teaching, research and service. It seeks to invest in programs and services that address issues and challenges affecting the diverse ethnic and socioeconomic population of Texas and the larger society, including the global arena.” I ended up categorizing this donation to an HBCU as an equity grant. I considered putting it into the justice category based on some advocacy, but the university is not fundamentally trying to change systems. My philanthropy professional also put this in the equity category, while my poli-sci professor considered it status quo grantmaking.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 equity, 1 status quo

9. Enterprise Community Partners — Its mission is “to make home and community places of pride, power and belonging. We focus on the greatest need, the massive shortage of affordable rental homes, to (1) increase the supply of affordable homes, (2) advance racial equity and (3) build resilient communities and ensure upward mobility for all.” I put this down as equity work because it is especially focused on racial equity in housing. It has some legitimate justice organizing, engaging in policy work to advocate for change. But it is not clear how much of that advocacy work takes its cues from the voices of those most deeply affected. The philanthropy professional put this grant into the justice category, while the poli-sci professor said they couldn’t decide if it was government backstopping, status quo or equity work.

Majority, Not Justice: 1 equity, 1 justice, 1 gov back

10. National 4-H Council — Its mission is “to expand opportunities for all of America’s youth through increased investment and participation in 4-H positive youth development.” Having grown up in a poor rural community, I initially perceived this to be an equity grant, but upon closer inspection, I came to the conclusion that it more likely belongs in the pro omnibus category. And both of my fellow reviewers agreed that’s where it fit.

Unanimous, Not Justice: 3 pro omnibus

So how much of a social justice grantmaker is MacKenzie Scott, based on her largest grants? Those top 10 totaled $535 million in gifts, and only two organizations (Co-Impact Gender Fund and Amref Health Africa, totaling $125 million) were perceived by most of the reviewers to be doing justice work. The dollar amounts to those two organizations are about 23% of the dollars going to the grantees at the top of the list.

For those tracking equity dollars, only two of the remaining grants were to organizations that the majority said were doing equity work. These were both $50 million grants, so you could say another $100 million (or a little under 20%) went to equity work. Combining justice and equity work, as many do, totals $225 million, or about 42% of Scott’s top 10 giving.

In other words, 58% of her top-dollar giving goes to organizations that reviewers perceived to be doing neither justice nor equity work using our continuum definitions, making a pretty conclusive case based on our rubric that justice funding has not been the top priority among her largest grants to date.

Among 10 randomly selected recipients, we categorized two as doing justice work

For the remainder of the grants, we took a random sampling and followed the same process. For the sake of brevity, we’re only listing the final ratings in this set.

Goodwill Industries of Kansas

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 equity, 1 status quoBoys & Girls Clubs of Sonoma-Marin

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 gov back, 1 status quoThe Praxis Project

Unanimous, Justice: 3 justiceCommunities In Schools of Mid-America

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 gov back, 1 status quoYWCA South Florida

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 equity, 1 pro omnibusSou da Paz (Sou da Paz Institute)

Majority Justice: 2 justice, 1 gov backUbuntu Pathways

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 equity, 1 gov backDonors of Color Network

Majority, Not Justice: 2 equity, 1 justiceNonprofit Finance Fund

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 pro omnibus, 1 status quoTopeka Habitat for Humanity

Unanimous, Not Justice: 2 pro omnibus, 1 equity

Given that so many social justice nonprofits are smaller organizations that are less likely to be able to receive the massive grants of the top 10 list, I thought perhaps a greater percentage of grants in the random-number-generated list would be for social justice work. But that appears not to be the case.

In terms of the number of grants, it was exactly the same as the largest 10: only 2 in 10 of the randomly selected grants were perceived by the majority of reviewers to fit the continuum’s definition of justice work (The Praxis Project and Sou da Paz, totaling $5.2 million). Several of these grants had dollar amounts withheld so we weren’t able to calculate funding percentages among this set.

Of those eight non-justice grants, four were perceived by the majority of reviewers to be equity-focused. So if you group justice and equity grantmaking together, you could say that 6 in 10 of these randomly selected Scott grants are for justice and equity, which is higher than the grants at the top of her list. Still, only 2 in 10 grants does not suggest that Scott is making justice work, under the definition of systems change, the priority in this random selection of smaller grants either.

Is Scott shifting power in a way that makes her a social justice grantmaker?

One of the main observations of “Philanthropy, Social Justice and Shifting Power” was that philanthropic and social justice leaders felt strongly that what constitutes justice grantmaking is not just where the dollars go. They said that the practices major donors and giving institutions employ and the degree to which those practices contribute to shifting power in philanthropy cannot be entirely separated from where the money goes.

The areas of power-shifting they named included: flexibility of donor directives; board composition and control; transparency; staff connectedness to communities; community engagement in setting strategy and grantmaking (including participatory grantmaking); trust-based philanthropy practices; moving major funds to intermediaries or collaborative funds; and simply giving much larger portions of available resources away.

So does the way Scott gives alter our perception of her as a “social justice grantmaker?” She is certainly giving away a much greater portion of her wealth than any other donor or institution you could name. By December 2022, she had given away over $14 billion, and at the time, her net worth was estimated at $27 billion. That means she’s given away about a third of her wealth, which few donors or institutions can claim (we see you, Chuck Feeney). So on that aspect of power-shifting, which many in the social justice field say is paramount, she’s doing quite well.

She’s also giving almost entirely general operating support dollars with few strings attached, so she’s employing key elements of trust-based philanthropy (although without the relationship-building that is also a part of that approach’s framework). It can also be said that her “donor directive” is quite flexible; in fact, it’s so broad that it is difficult to say what she really wants to achieve besides avoiding the criticism that she’s trying to control anyone or anything.

On the other elements of power-shifting associated with perceptions of justice grantmaking, she has come in for considerable criticism. There is no board of directors and nobody knows how decisions are really made between Scott, Bridgespan Group and the consultants/advisors in the field communicating with potential grantees. Scott’s new Yield Giving website is a notable step toward transparency, but on the whole, she has been vague about her giving priorities, how to contact her representatives and other key elements associated with transparency best practices. It’s impossible to say what kind of connection her team has with communities or whether there is any engagement with communities to set giving strategies or participate in grantmaking.

One final observation on power-shifting: Scott’s giving is often discussed as a positive counterpoint to endowed foundations that “hoard” money and power. Her large gifts supposedly put significantly more power into the hands of people on the front lines to decide how to resource their future. I have relationships with several organizations that have received Scott grants, and it seems to me that the amount she gives, generally, is roughly the size of the organization’s annual operating budget. These gifts are a significant cash infusion, but hardly enough to endow the organizations so that they no longer need to rely on fundraising from those who hold power to continue doing their work. She could be providing targeted funds large enough to permanently endow social justice organizations. But instead, her giving is not strategically focused enough to significantly change the operating environment in which social justice organizations still need to go hat-in-hand seeking donations into the future.

On the power-shifting front, Scott’s giving practices are a mixed bag. From my perspective, how she gives doesn’t impact my overall perception of her philanthropy, which is based on what she’s giving to. Others feel that giving such large sums for general operating support is fundamentally shifting power in the sector. The question remains: If the rest of her $27 billion goes out the door in the next few years, will the terrain look fundamentally different for organizations seeking systemic change?

Fundamentally changing systems hasn’t been Scott’s primary focus

This is just an examination of 20 grants. Maybe a larger sample or a full study of all of her grants would come to a different conclusion. Perhaps reviewers with different perspectives might place her grants on different points on the justice-regression grantmaking continuum. This really is just a starting point for conversation.

The analysis does, however, paint a picture of a donor who is supporting a staggering range of nonprofits pursuing all kinds of missions, with only a portion of her giving going to justice-focused organizations working to change systems.

That’s not to say the rest is funding unjust work, nor is it intended as criticism of the groups she is funding. As noted, none of the reviewers perceived any of the 20 grants to be located in the “self-serving” or “actively regressive” areas of the grantmaking continuum, and there were very few designations of status quo grantmaking by the reviewers. While it seems that 20% of grants are going toward justice work as the field is increasingly defining it, and just about half of her grants are going toward either justice or equity work, she’s still likely directing a ton more money toward these categories than pretty much any other major donor or philanthropic institution you could name.

To sum up: Based on the small ratio of her giving to justice-focused organizations, Yield Giving is not prioritizing “justice grantmaking” as the field increasingly defines it. A closer examination of all of her grantmaking — not just the 20 grants we’ve examined here — could validate the analysis we’ve made with our limited sample, and might confirm our theory that the majority of her grantmaking isn’t for justice work.

There is much to applaud in MacKenzie Scott’s giving, but let’s not dub her this era’s leading funder of social justice, at least not yet.

Michael Hamill Remaley is the editorial director for Inside Philanthropy’s State of American Philanthropy initiative. He is also an independent consultant to foundations and nonprofits.