The Dollar Amounts Are Historic, But Here’s Why We’re Really Bullish About Two Recent HBCU Gifts

/Broadmoor, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The year’s off to an auspicious start for historically Black colleges and universities. On January 11, the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) announced it received an unrestricted $100 million grant from the Lilly Endowment that it will apply to its $1 billion campaign to boost the endowments of its 37 partner schools. It’s the single largest unrestricted gift to the fund since its founding 80 years ago.

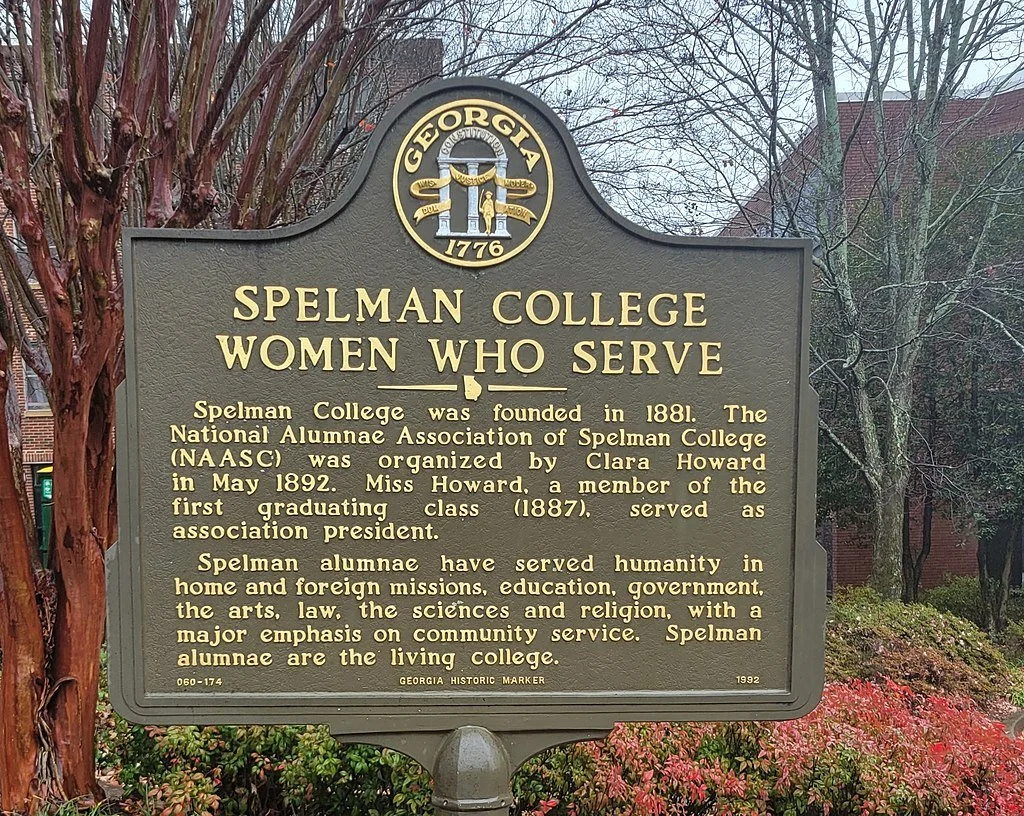

A week later, Atlanta’s Spelman College received a $100 million donation from Rhonda Stryker and William Johnston earmarked for scholarships, academic programs in public policy and democracy, and student housing. Spelman celebrated it as the largest single donation ever to an HBCU.

The gifts, which came four months after Blue Meridian Partners awarded $124 million to the HBCU Transformation Project, might very well suggest that schools have capitalized on surging donor interest in the wake of 2020 and are chipping away at deeply entrenched funding disparities. Unfortunately, that would be a somewhat inaccurate takeaway.

While the field was flush after the 2020 racial justice protests, HBCUs netted a mere three publicly announced gifts totaling or exceeding $1 million in 2022, according to HBCU Money. Last May, I spoke with Susan Taylor Batten, president and CEO of ABFE, to discuss takeaways from a report titled “Philanthropy and HBCUs” conducted in partnership with Candid. Batten who told me that foundation support for HBCUs was tapering off. “We haven’t done a rigorous study,” she said, “but we are hearing from members on the foundation and nonprofit side, and there is a waning of interest — ‘George Floyd fatigue.’”

With that in mind, it would be presumptuous to think these nine-figure gifts are anything like a “new normal” for the field. That said, these are donations of a mostly unprecedented nature for HBCUs — massive follow-on gifts from incredibly affluent funders who will only become wealthier over time, creating a virtuous cycle in which advancement officers can reasonably count on more support in the future.

That cycle repeats itself year after year, wealthy donor after wealthy donor, at affluent, predominantly white institutions across the country. But up until now, it’s been an exceedingly rare phenomenon in the HBCU field.

Textbook mega-giving

The Stryker/Johnston and Lilly donations adhere to one of the cardinal rules of higher ed fundraising: Mega-gifts are usually preceded by a smaller gift or a series of smaller gifts. Extreme wealth tends to beget even more extreme wealth, which incentivizes funders to make larger gifts over time. In many cases, that support flows to previous grantees.

In 2018, Stryker and Johnston gave Spelman College a $30 million donation to support its new Center for Innovation & the Arts. At the time, it was the largest public gift to an HBCU. The Lilly Endowment, meanwhile, has supported the UNCF for decades, and in 2015, it donated $50 million to the fund’s Career Pathways Initiative.

Last July, I took a look at Stryker and Johnston’s giving, which primarily focuses on their hometown of Kalamazoo, Michigan. Stryker, who did not attend Spelman but has been a trustee since 1997, derives her wealth from stock in the Stryker Corporation, a medical technology company founded by her grandfather. Her fortune currently tops $7 billion.

Stryker has a penchant for selling shares every few years to bankroll her charitable ambitions. For example, she sold $142 million worth of stock between May of 2022 and 2023, which led me to theorize that another bump in giving might be on the horizon. Now that this low-risk prediction has come to pass, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to assume that the 70-year-old Stryker will continue to unload stock every few years and that a portion of that windfall may make its way to Spelman.

The Lilly Endowment, meanwhile, is contending with its own ever-growing pile. Last March, my colleague Michael Kavate reported that its endowment had swelled to $32.8 billion at the end of 2021, thanks to gains in the price of Eli Lilly and Company stock, which makes up the bulk of its holdings.

If only to keep pace with the 5% minimum grantmaking threshold for foundations, Lilly will need to start moving a lot more money out the door, fast, even if Eli Lilly and Co doesn’t end up becoming the “first trillion-dollar healthcare stock.” And that already seems to be happening — on January 9, two days before its $100 million UNCF gift was made public, the endowment announced a separate $100 million commitment to Purdue University. Given all that, I think it’s fair to assume Lilly will provide additional support to UNCF in the future.

Paradigm shift

When super-wealthy funders provide nine-figure follow-on gifts and will likely make similar gifts down the road, administrators have the breathing room they need to make impactful budget decisions without losing sleep over imperiling their institution’s financial sustainability. While this distinct brand of giving is standard operating procedure at affluent, predominantly white institutions, that hasn’t been true in the HBCU field, where, despite considerable support from an array of affluent donors, the combined endowments of all 102 schools, $4 billion, would rank 22nd among the endowments of the nation’s wealthiest four-year universities.

This disparity is rooted in demographic realities, such as the fact that HBCUs often lack a deep bench of affluent alumni. In addition, the field has had to push back against debilitating stereotypes. For many years, while advancement officers at wealthy universities ironed out the details of the latest hedge fund alumni mega-gift, their peers at HBCUs found themselves defending administrators’ ability to responsibly manage their schools’ finances, or explaining to prospects that their comparatively lower graduation rates were traceable to a dearth of college-prep opportunities and financial safety nets among many Black students. While fundraisers at affluent schools were counting the zeros, those at HBCUs were justifying their existence.

But that was then. For the Associated Press’ coverage of the Lilly gift, UNCF President and CEO Michael Lomax said, “Donors today no longer question the need for HBCUs and instead ask how gifts to the schools can have the largest impact.” As clichéd as it may sound, this is the textbook definition of a paradigm shift. The bigger question is whether advancement officers can capitalize on this shift by engaging more donors, especially those in the mold of Stryker/Johnson and Lilly — the affluent repeat funders prone to making the sort of mega-gifts that fuel wealthier, predominantly white institutions’ fundraising machinery.

Regaining momentum

It’s a tall order, especially given the idea that prospects are experiencing “George Floyd fatigue,” as Batten at ABFE put it last year. But as Lomax noted, HBCUs have made tremendous progress in reshaping funders’ perceptions, and there are a few ways the field can further sharpen the optics to galvanize support.

One of the big takeaways from the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s invaluable research on the impact of MacKenzie Scott’s large, unrestricted gifts — which include numerous HBCU donations — is how recipients leveraged that public stamp of approval to raise money from other funders. In the same way, the Stryker/Johnson and Lilly mega-gifts may impel other funders to give HBCUs a second look.

In a similar vein, unlike most higher ed donations, Lilly’s gift to the UNCF was unrestricted, reflecting the endowment’s Scott-like belief that the fund could be trusted “to make a decision about where best to deploy this very significant and sizable gift,” Lomax said. “We don’t get a lot of gifts like that.” A $100 million public declaration of trust may resonate with funders who previously lacked confidence in HBCUs’ ability to manage their finances.

Then there’s the fact that the Lilly gift will support the UNCF’s efforts to increase the unrestricted endowment for each of its 37 member institutions by $10 million, doubling the endowments at several institutions. Lomax said the UNCF has raised $550 million toward the campaign’s $1 billion goal, which he called a “floor” and not a “ceiling.” Funders are drawn to organizations on firm financial footing — the adage “it takes money to make money” comes to mind — so the UNCF’s plan may make risk-averse funders more inclined to cut a check.

The last cause for cautious optimism pertains to broader cross-currents following the Supreme Court decision to abolish affirmative action. Speaking to my colleague Ade Adeniji last July, Spelman alumna and fundraiser Mildred Whittier said HBCU alumni will likely dig deeper to help their alma maters brace for the anticipated surge in applications after the decision. “What I’ve seen in some articles I’ve read is that [there are signs] that attendance at HBCUs will increase as a result of that ruling,” she said. “And when we’re looking at more applications coming into HBCUs, this gives rise to the need for more funding.”