Here's the Problem With Philanthrocapitalism in Africa

/

Among other projects, Theroux cites Jeffrey Sachs’ $120 million dollar effort to end extreme poverty in Dertu, Kenya. “Sachs' Millennium Villages Project poured $2.5 million over three years into a sparsely populated community of nomadic camel herders in Dertu, Kenya, and trumpeted its success. In actual fact, the charity's paid-for latrines became clogged and overflowing, the dormitories it erected quickly fell into disrepair, and the livestock market it built ignored local nomadic customs and was closed within a few months.” Intended as a bottom-up enterprise, Theroux suggests, it imposed market dynamics from the top-down in a way that couldn't be sustained in the long-term.

Theroux’s general thrust is that for all the discussion of “rethinking” how philanthropy works in Africa, little has changed in around 170 years. Western philanthropists are likely to come from business backgrounds, often misapplying their career lessons to an environment without the infrastructure to support business principles.

This has been going on since the Victorian era, but each successive generation reinvents the concept and thinks that they’re the first. The new generation of philanthropists calls it “philanthrocapitalism,” but it’s not much different from the capitalist star that guided David Livingstone or the market-based social reforms that drove abolitionist Thomas Buxton in the 19th century.

Philanthrocapitalist ventures have built roads, cured diseases, improved sanitation, and educated populations, and it’s the right tool for certain jobs. But the theory so far fails to address the many social problems that have no clear connection with market principles. A perfect example is the prevalence of orphans in Malawi, about which Theroux writes,

The lamentable fact of so many orphans is something the new investment-minded donors, scornful of check-writing philanthropy, seem to overlook. Unless an orphanage is turned into a Dickensian workhouse, with manual labor as its primary purpose, there is no way for such an institution to turn a profit; and so such places depend on cash handouts, nearly all from telescopic philanthropists, and meanwhile the orphans, like the ones in Malawi Children's Village, try to be self-sufficient by tending vegetable gardens, doing household chores, helping with the upkeep and at the same time studying at local schools.

Last week, the New York Times highlighted nonprofit organization D-Rev. Their social-entrepreneurism mission involves the inception and engineering of first-rate medical equipment customized for the needs of developing countries, then licensing the designs to for-profit distributors in target regions including India and Africa. These market-based principles collided with the realities of cronyism and corruption in many cases, and chief executive Krista Donaldson told the Times, “We thought if you design a good product, it will scale on its own. That works in efficient markets, but most developing communities don’t have efficient markets.” As a result, D-Rev has become much more intimately involved with locally marketing their products and services than they'd ever intended.

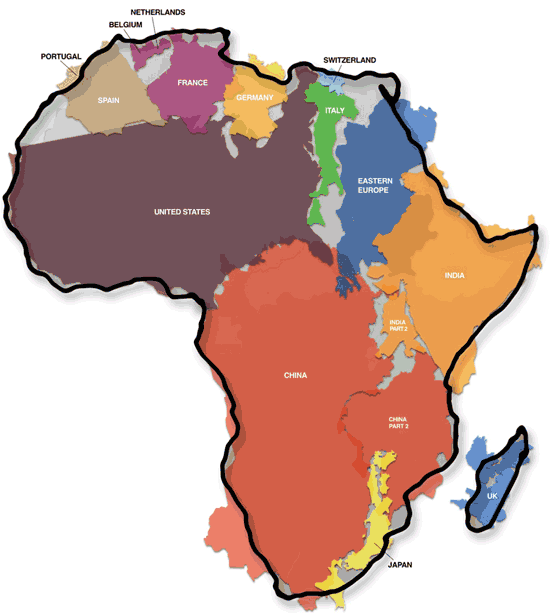

Recently, graphical user interface designer Kai Krause illustrated the vastness of Africa with an amazing viral infographic passed around the internet under the heading “Every World Map You’ve Ever Looked At is Wrong.” Across such a huge continental expanse, philanthropy can disperse like a fine mist if not directed at the right target.