Thirty Million People Face Starvation Right Now. Are Funders Paying Attention?

/Eritrea is among those places facing famine

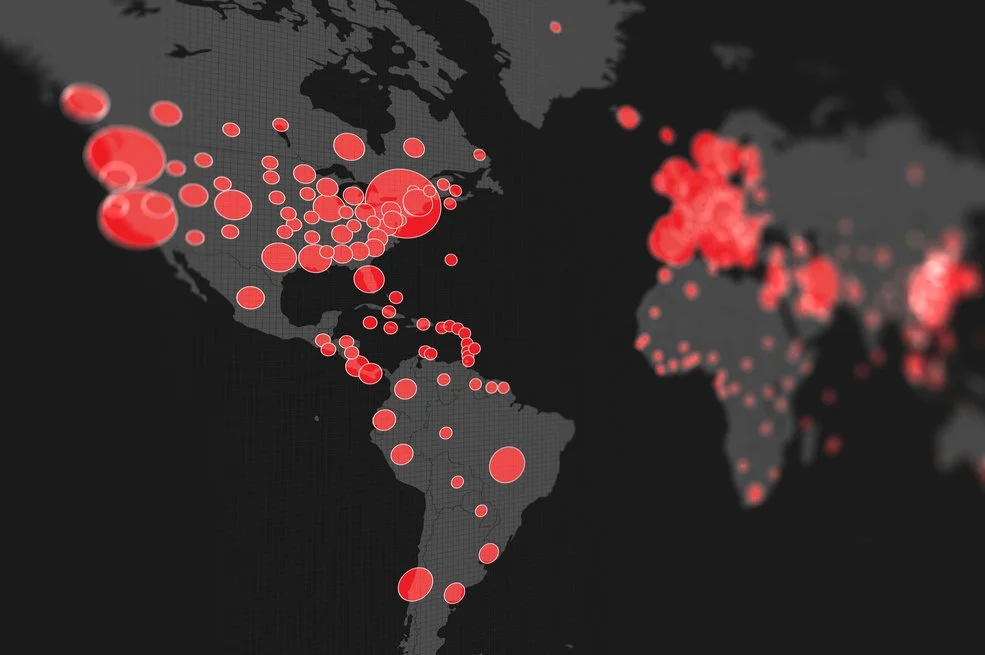

War and conflict have driven some 30 million people to the brink of starvation in South Sudan, Nigeria, Yemen, and parts of East Africa. As of May 2017, around 5.5 million people in South Sudan alone are “facing severe food insecurity and are in desperate need of humanitarian assistance." The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) describes the conflict in South Sudan—which suffered a breakdown in peace talks in 2016—as the “biggest new factor” in the refugee crisis. Making matters worse, most of the countries hardest hit by the current famine are entering their lean seasons.

With less than half of an urgent United Nations appeal for $1.64 billion funded, it doesn’t look like adequate help is coming anytime soon from national governments and international agencies.

What about private philanthropy? The world's 2000 or so billionaires have over $7 trillion in assets. Surely, some of them are stepping forward to prevent the starvation of millions of people on a planet that's never been wealthier. Right? Or what about the big American foundations, with their multi-billion-dollar endowments? You'd think alarm bells would be ringing here, too, as the world faces what could be the biggest humanitarian crisis of modern times—a hellish convergence of multiple famines in parched regions wracked by war.

Well, if you're a regular reader of IP's coverage of humanitarian disasters, you can probably surmise how the rest of this post will go.

As usual, wealthy philanthropists and major foundations aren't taking the kind of large-scale and urgent action that could make a big difference in this situation. The reasons—some understandable, others unforgivable—have become familiar.

Big funders like the Gates or Hilton foundations already have giving programs and grantmaking priorities in place. While both are dialed in to alleviating human suffering in humanitarian crises, they’ve already made major commitments to top aid organizations responding to crises around the world. Short of dipping into their endowments or rearranging program priorities, it's hard to lay out more grant money.

(Although, just for the record, Bill Gates has a fortune of nearly $90 billion that's separate from his foundation's endowment. He and Melinda have pledged to give away most of their wealth. You'd think now might be a good time to ramp things up in this regard.)

Another likely reason more funders aren't stepping up is that these famines are largely occurring in countries mired in conflict, and in some cases, partly controlled by rebels. In South Sudan, for example, rebels rejected the permits necessary for planes loaded with emergency food and medical supplies to take off from local airfields. The country’s government was also threatening to require every aid worker in South Sudan to have a license at the cost of $10,000 each. Yemen is another very dangerous place.

Beyond a fear that money might not reach those who are starving, another factor, here, is the sheer scale of this crisis, which seems beyond the capacities of private philanthropy. Funders tend to like tackling more discrete and solvable problems, and many of them shy away from giving that feels like Band-Aid work.

As we've argued in the past, though, none of these excuses really stand up to scrutiny. UNHCR and other relief providers are begging for extra resources that they have confidence can be deployed effectively to save lives. And sure, it'd be nice if governments were adequately addressing the problem, but they're not—and there are clear ways that private donors can fill the gaps, here. Finally, as we observed the other day in an article about Jeff Bezos' philanthropy, there's a strong case for more donors backing the kind of "here and now" work that Bezos said he was inclined toward. It doesn't make sense for the supposedly smart money in philanthropy to be so fixated on improving humanity's well-being when there's so much urgent relief work that needs to be done in the short term.

Related: Hey, Jeff and MacKenzie Bezos: Here Are Some Ideas for Your Philanthropy

Not all the news is grim, though. Ordinary individual small donors—those who never got the memo telling them to avoid wasting their money on gifts that actually keep people alive—have a strong record of coming through at moments like this, with donations going to top NGO relief groups like Bread for the World. Overseas faith-related giving is a huge lifesaver when famines hit, and many organizations in this space are highly mobilized right now, blitzing supporters with urgent appeals. Also, in April of this year, the British public raised a collective £50 million in less than one month. That money is providing people in East Africa with food, water and medical care.

Some celebrities are stepping forward, too. In the “out of left field” category, the unlikely threesome of former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, actor Ben Stiller, and “social media star” Jerome Jarre convinced Turkish Airlines to donate one of its 60-ton cargo planes to deliver food and water to the people of Somalia. To date, Jerome Jarre’s GoFundMe campaign Love Army for Somalia, has raised nearly $2.7 million.

And while the Trump administration threatens to cut foreign aid, other governments are stepping up. Earlier this year, Britain’s Department for International Development (DfID), announced its plans to allocate £100 million for “new humanitarian support for South Sudan."

International aid officials are describing the protracted African famine as “one of the biggest humanitarian disasters since World War II.” Now, where have we heard that comparison before? Oh right, the global refugee crisis—a crisis that had engulfed 65.6 million people by the end of 2016. Much like that humanitarian catastrophe, the famine in Africa has so far been largely ignored by the philanthropic community.

Does this really come as a surprise? Unfortunately, no.

Related: Yemen: Another Humanitarian Crisis That Poses a Test for Philanthropy