Principle vs. Impact: When Should Institutions Keep Tainted Donations?

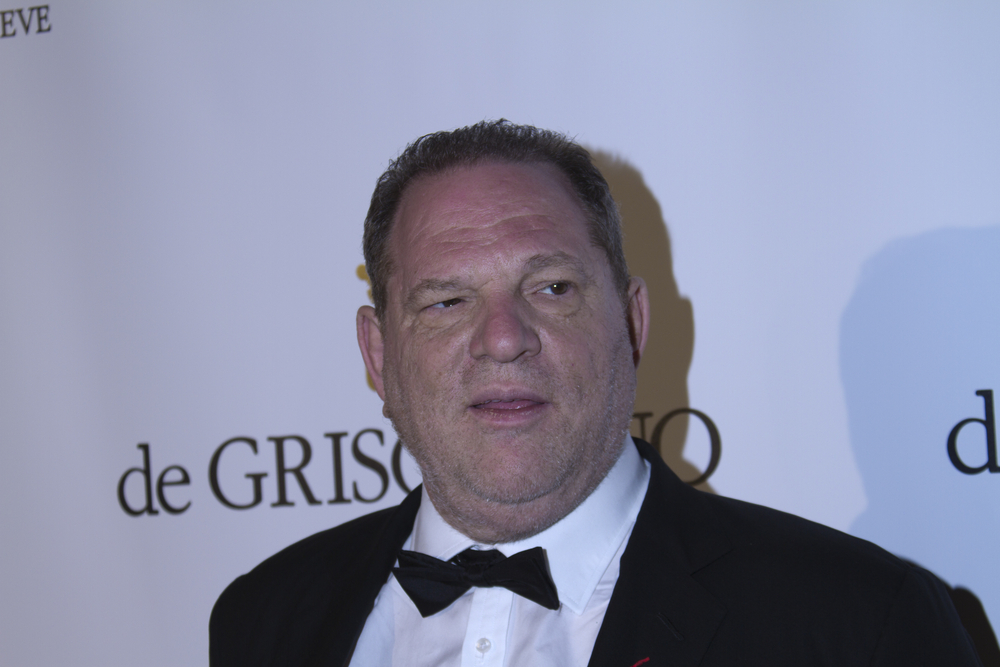

/Harvey weinstein. photo: Denis Makarenko/shutterstock

The extent to which nonprofits need to consider the moral character or ideology of their donors is a question that we've wrestled with before at Inside Philanthropy. Should it really matter who the money comes from, and if it does, how does one draw that line of distinction?

The question is as old as modern philanthropy itself. A century ago, debates raged over whether John D. Rockefeller and other Robber Barons should be able to reinvent themselves as benefactors. More recently, nonprofits have struggled with how to deal with gifts that are tainted in one way or the other.

It's a classic cost-benefit analysis that we saw play out most acutely on university campuses after Bill Cosby's sexual assault allegations came to light. Administrators grappled with how their decisions regarding Cosby's donations would affect the school's reputation and academic standing—but also the harm to programs of returning these gifts.

Many times the course of action is self-evident. There wasn't too much ethical handwringing when Ohio University took alumnus Roger Ailes' name off a campus newsroom and returned his $500,000 gift after his transgressions surfaced.

But other times, the matter is more complicated. An instructive case study has emerged thanks to the #MeToo movement. It involves a $5 million gift in a critical funding space.

A Sector in Need of a Boost

One of the hottest issues in film philanthropy right now is boosting gender equity. Funders like the Adrienne Shelly Foundation, the Will and Jada Smith Family Foundation, New York Women in Film & Television, and the Sundance Institute are all giving to ensure that women are better represented across the industry.

It's encouraging stuff, but there's much work to be done. A recent study from the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film found that in 2017, women comprised 18 percent of directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors and cinematographers working on the top 250 grossing films.

This represents an increase of 1 percentage point from 17 percent in 2016, and is virtually even with the number achieved in 1998.

The inference here is clear: Progress has been frustratingly incremental. The cause of gender equity in film needs greater attention and also more funding. If new gifts come from Hollywood insiders to add extra gravitas, all the better.

The good news is that USC's School of Cinematic Arts, one of the country's preeminent film schools, received a $5 million pledge to endow grant scholarships for women filmmakers. The bad news is that the Hollywood insider who made that pledge was Harvey Weinstein.

"We Don't Need This Money"

Let's put Weinstein's $5 million gift in context. Scan this list of grants available to female filmmakers and you'll see that the largest grant, at $120,000, is the Women in the Director's Chair Telefilm Nominee.

The list is not comprehensive. For example, it omits the Adrienne Shelley Excellence in Filmmaking Award ($5,000) and the Will and Jada Smith-funded Fusion Festival awards for female filmmakers ($10,000.)

But you can see where I'm going with this. At the expense of falling back on overused platitudes, Weinstein's $5 million gift had the potential to be game-changing in the truest sense.

Then the New York Times published its investigative bombshell alleging Weinstein's decades of harassment and abuse. In response, Weinstein released a statement saying, "I came of age in the '60s and '70s, when all the rules about behavior and workplaces were different," while also noting that his USC gift was still on the table.

"While this might seem coincidental, it has been in the works for a year. It will be named after my mom and I won't disappoint her," his statement read.

A statement from USC confirmed Weinstein's timeline, saying, "[We] began discussions with Mr. Weinstein over a year ago to fund a $5 million endowment in his mother’s honor dedicated to scholarships for women filmmakers, particularly those from minority communities."

After news of Weinstein's alleged crimes broke, a USC student named Tiana Lowe launched a petition on Change.org calling on the school to refuse what she called "Harvey Weinstein's blood money."

"We are blessed with the expansive and charitable Trojan family," Lowe wrote. "We don’t need this money. What we need is some damn principles."

Within hours, the petition had gathered more than 300 signatures. In mid-October, the school issued a statement to the Hollywood Reporter stating, "The USC School of Cinematic Arts will not proceed with Mr. Weinstein’s pledge to fund a $5M endowment for women filmmakers."

The Question of Cumulative Impact

Before I look at the implications of USC's decision, I'd like to loop back to the school's statement that corroborated Weinstein's timeline. Nowhere does it say that Weinstein's check cleared and that $5 million was sitting in the bank. Rather, it appears as if the gift was still in its formative stages. This is an important detail.

In the past six months, we've learned that Weinstein can't afford to pay child support. What little money he has is going to an army of lawyers fending off dozens of potential lawsuits. And his production company is $500 million in debt and considering bankruptcy.

Even if USC "accepted" Weinstein's $5 million, would it ever actually see the money? It's unlikely, which made its decision a bit easier to rationalize.

But for argument's sake, let's say the money was there for the taking.

Would USC have experienced pushback if Weinstein gave $5 million to, say, the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center? I'm not so sure. One can make an argument that $5 million for cancer research, even if it came from someone like Weinstein, is worth the trade-off.

It's a lot harder to make a similar argument for cultivating female filmmakers, which is unfortunate, especially when one considers the potential cumulative impact of a gift of this magnitude. Students receiving Weinstein-funded scholarships would eventually graduate, enjoy professional success, and give back. They could be role models and mentors to other women trying to get into film. Some might have started their own scholarships or funding entities to advance the cause of gender equity, creating a snowball effect.

Assuming the money was there for the taking, the argument ultimately boiled down to a choice with practical and moral implications. Should USC accept Weinstein's millions and catalyze a lagging sector of arts philanthropy? Or should it stand on principle?

USC opted for the latter. One organization that chose the former was the Clinton Foundation, which said it planned to keep a six-figure donation from Weinstein, explaining that the money has already been spent on programs.

“We are a charity," the foundation said in a statement to the Washington Times regarding Weinstein's gift. "Donations, these included, have been spent fighting childhood obesity and HIV/AIDS, combatting climate change, and empowering girls and women, and we have no plans to return them."