Making Amends: How Funders Can Address Slavery’s Legacy

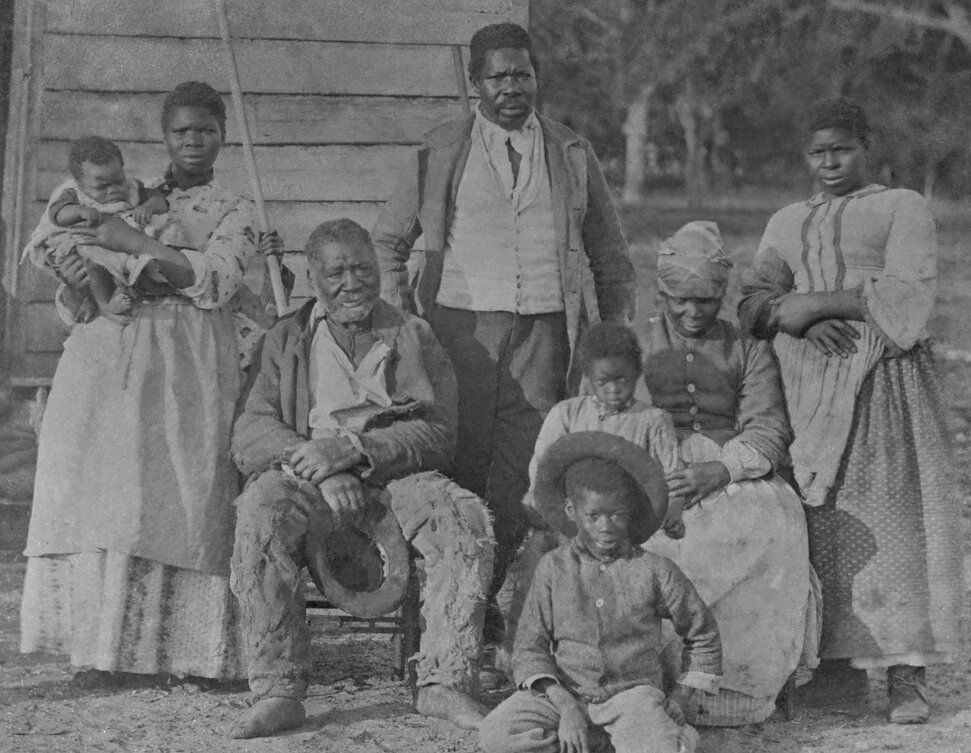

/A slave family on a plantation in Beaufort, South Carolina. Everett Historical/shutterstock

The 400th anniversary of slavery in the U.S. came and went this summer, and it’s an apt time to remember how much of America and its economy were built on this brutal and fairly recent practice. In an article for the New York Times series “The 1619 Project,” Princeton Professor Matthew Desmond said slavery “didn’t just deny black freedom, but built white fortunes, originating the black-white wealth gap that annually grows wider.” Desmond pointed out that less than two average American lifetimes of 79 years have passed since slavery ended.

The enslavement of Africans (along with the exploitation and abuse of indigenous peoples and numerous other ethnic groups) has unevenly distributed wealth and opportunity in the U.S. Despite progress, the 2008 housing crisis reversed many of the economic gains of black communities. As of 2016, an average black family had a net worth $800,000 less than the average white one. The rise in hate groups and white supremacist terrorist attacks, the increased documentation and media coverage of police abuses of people of color and the corresponding Black Lives Matter movement, and the conflicts surrounding confederate monuments prove that our culture still has a long way to go.

In 2011, less than 2 percent of funding from the nation’s largest foundations specifically targeted the black community. Because slavery played a central role “in the economic development of the country, it really ought to be a priority for every foundation to think critically about what their responsibility might be to begin to make amends for the crime that generated so much of our shared wealth,” Ryan Schlegel, National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) director of research, says. Because slavery’s effects are so far-reaching, there are nearly countless ways to bring these ramifications to light and address them.

For example, a recent $1 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to the College of William and Mary is one example of how a funder can approach the legacy of slavery within the humanities. It will support research and education pertaining to the college’s history with enslaved people. During my research for this article, I discovered that several Mellon family ancestors enslaved people, which raises interesting questions about how a foundation can approach this issue in its own history.

Philanthropy relating to slavery and its legacy is a huge, humbling topic, and I don’t aim or claim to be exhaustive. Rather than focus on the specific ways philanthropy engages in racial equity work in various issue areas, I’ll explore how some foundations and nonprofits are starting to grapple directly with slavery itself, its repercussions, and its ties to U.S. institutions. I’ll explore some funding approaches related to slavery research, the racial wealth gap, and community truth and healing processes, along with black-led change as a meta-strategy.

While discussing slavery’s destructive effects, it’s important to remember that the story of black America is undoubtedly one of incredible resilience and achievement. Funders and service providers can source the existing power and assets of black communities to steer and fuel their programming.

The Mellon Foundation Addresses Slavery in Higher Education

Slavery increasingly crops as an issue on college campuses. The slavery economy and its partner industries financed northern schools like Columbia, Harvard, Princeton and Yale, while southern schools like the University of Virginia (UVA) and William and Mary were directly built and serviced by enslaved people. UVA in Charlottesville, where the fatal Unite the Right rally began in 2017, has run a program called Universities Studying Slavery since 2014, which has about 40 member schools.

In recent years, we’ve seen Brown, Yale, Harvard, Rutgers, Columbia, Princeton, the University of Richmond and other schools address this topic by renaming buildings, hosting conferences, publishing reports, and studying enslaved people’s burial grounds. In September 2019, Virginia Theological Seminary (VTS) set aside $1.7 million to pay reparations pertaining to the enslaved people who worked on its campus. The money will support local congregations linked to VTS, fund the work of black graduates and meet “the particular needs” of the descendants, along with other purposes.

Such efforts aren’t limited to the U.S.—in August 2019, Glasgow University in Scotland agreed to pay 20 million pounds (about $25 million) in reparations related to its links to the slave trade. The money will fund the Glasgow-Caribbean Centre for Development Research. Glasgow University, the University of Bristol in England and Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia participate in UVA’s slavery studies program.

In 2017, Georgetown received a $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to establish new racial justice initiatives on campus. In late July 2019, Mellon announced a $1 million grant for slavery-related research and learning at William and Mary. This funding aligns with the foundation’s overall mission to support humanities and arts in institutions of higher education and culture, to which it dedicated almost $311 million in 2018.

Diversifying faculty and “improving the educational attainment of historically underrepresented groups” are among the foundation’s general race-related goals in higher ed. Elizabeth Alexander, who became foundation president in 2018, said she wants the organization to view its work through a social justice lens. Alexander is an awarded black female poet, a former director of creativity and free expression at Ford, where she co-designed the Art for Justice Fund, and a former professor of Yale and other universities.

The latest funding for William and Mary was carefully timed to align with the 400th anniversary of slavery’s start in America. The five-year grant will fund a project called “Sharing Authority to Remember and Re-Interpret the Past” through two existing research bodies. One is the Lemon Project, which will conduct genealogy research regarding the enslaved people who built the main campus, which will inform its Memorial to African-Americans Enslaved. Mellon has funded William and Mary and the Lemon Project in the past.

The second research project is run by James Monroe’s Highland, a house museum of the fifth president that is part of William and Mary, Monroe’s alma mater. Highland will use the funds to further its Oral History Initiative, which preserves the stories of the descendants of enslaved people. The grants will also back a college course based on the research. I connected with the Mellon Foundation about this grant, as well as the Mellon family’s historic ties to slavery, but they declined to contribute to this story.

“By partnering with their descendants to conduct new research and share it widely with the public, William and Mary demonstrates how building meaningful partnerships can move communities toward reconciliation and lift up histories that have not yet been fully understood,” Alexander said in a statement. Sharing authority with and listening to impacted communities are recurring themes throughout philanthropy to address slavery’s pervasive after-effects.

The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation is named for a patriarch of the wealthy Mellon family, which has deep roots in American finance. The foundation was created in 1969 through the consolidation of two foundations started by Andrew W. Mellon’s children. He was a prominent financier and industrialist, a conservative Republican and an influential and controversial U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. He lived from 1855 to 1937. He was also an art collector and arts-oriented funder—his money helped to build the National Gallery of Art, and he co-founded the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, which later became Carnegie Mellon University.

The Mellon family first immigrated to Pennsylvania from Ireland around 1815. Andrew W. Mellon’s father, Thomas, decided not to carry on the family trade of farming and became a judge and banker instead, laying the groundwork for Andrew to enter finance. Some Mellon ancestors enslaved people. Thomas’ autobiography, written exclusively for his family, described his uncle’s large cotton plantation in Mississippi as “well-stocked with slaves.” James Mellon, a descendant of Thomas, wrote a 2011 book, The Judge: A life of Thomas Mellon, Founder of a Fortune, reporting that a separate family line, described as “ancestors of the Mellons of Pittsburgh,” enslaved people in Pennsylvania.

The Mellon Foundation and family is clearly not alone in its ties to slavery. How should a slavery-linked funder that underwrites universities’ research into their own connections to the practice deal with this family history? Does such a foundation have a greater responsibility to address slavery’s legacy?

I posited this question to Dr. Lolita Buckner Inniss, senior associate dean for academic affairs and law professor at the Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law. She studies race, gender and law, contributed to the Princeton and Slavery Project, and wrote The Princeton Fugitive Slave: The Trials of James Collins Johnson. She says, “While it would be useful if such institutions acknowledged their [involvement] and acted to address it, there is a danger that in focusing on those who can be identified as actors, we might ignore the broader systemic responsibility for U.S. slavery.”

How Can Philanthropy Deal With Slavery’s Fallout?

Philanthropic attention for black communities and racial issues has increased in recent years—notably so since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2014 and the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Numerous funders try to loosen the nuts and bolts of racial inequity and support black communities’ success with myriad, overlapping strategies. They back projects relating to financial inclusion, affordable housing, employment, gun violence, criminal justice, healthcare and food access, programming for boys and girls of color, movement building, civic engagement, policy work, environmental health, and other challenges, opportunities and possibilities for black communities. These endeavors often naturally intersect with women’s, LGBTQ+, immigrant and disability rights, among other causes. Inside Philanthropy has also covered how funders can integrate racial equity into their internal structures and practices, and the growing calls for philanthropy to share more power with the communities it serves through participatory grantmaking and other practices.

From different angles, much of this work addresses the impacts of slavery, as well as the Jim Crow era and structural racism that followed. But typically, grantmakers rarely reference slavery directly; only recently has this begun to change. How should a foundation with documented ties to slavery, or any philanthropy interested in working in this specific area, frame its funding?

Schlegel of NCRP says it’s important for such foundations to remember that slavery wasn’t very long ago, and that it’s legacy “lives on” in our economic, criminal justice, health care and education systems. He thinks there are many things a foundation leader or donor can do to “reckon with this shared history.” He highlights three main strategies relating to power: Funders can build power for and share power with black people and communities, and wield their own power and influence “to push for racial equity and [justice].” The Philanthropic Initiative for Racial Equity (PRE), Black Social Change Funders Network (BSCFN) and the NCRP can provide resources for philanthropists interested in this kind of work.

BSCFN released a report in 2017 called “The Case for Funding Black-Led Social Change,” which elaborates on Schlegel’s arguments. Two key points of the report, as we reported in an interview with Nat Chioke Williams, executive director of the Hill-Snowdon Foundation, are that general racial equity funding is not the same as targeted efforts to strengthen black-led organizations, and that these groups have been a cornerstone of the social change sector. The report states an “unapologetic and persistent focus on anti-black racism is an essential strategy” against white supremacist ideologies.

Schlegel suggests building black power by funding black-led grassroots social change efforts, like “black residents of a gentrifying community [organizing] for affordable housing legislation… organizations pushing for re-enfranchisement for felons… [or] black parents organizing for more equitable investment in predominantly black schools.” Within the philanthropic sector, Schlegel says foundations can share power by hiring black staff to make funding decisions and inviting black-led organizations to advise grantmaking, among other options.

Philanthropy by black communities and individuals in the U.S. dates back to the period of slavery. Donors can support black-led and -focused funds, organizations and giving circles. There are many local, regional and national groups. The Young, Black and Giving Back Institute in Washington, D.C., established in 2014, is an example of a newer group, and the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), founded in 1944, is a well-established and still active example. The Association of Black Foundation Executives (ABFE), which runs the Black Philanthropic Network, is a core membership organization and resource.

Justene Hill Edwards, a UVA assistant history professor who studies African-American history, American slavery and capitalism, says funding historically black colleges and universities is a powerful way for philanthropists to respond to the legacy of slavery, “because these institutions historically have played such an important and vital role in expanding educational opportunities, not only for people of color, but for all Americans.” She also recommends investing in small, black-owned businesses. Philanthropy has also funded museums that explore black history in America. The Lilly Endowment, Robert Frederick Smith and Oprah Winfrey were the top funders of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The Mellon Foundation was also a major donor. Ford and the Stryker family, among other donors, helped to fund the Memorial to Peace and Justice, a national memorial to victims of racial terror lynchings in the United States, which opened last year in Montgomery, Alabama.

The philosophy holding that efforts to help or change black communities should be led by black people can be applied to funding for nearly any domain, strategy or scale. Concentrating on building up and tapping into black power also focuses on potential and strengths rather than deficits. Funders who want to use a more positive frame in their race-related programs can check out the BMe Community, which trains foundation and nonprofit leaders in "asset-framing for equity.” It advises funders and service providers on how best to define people by their aspirations and contributions before exploring their challenges.

Inside Philanthropy frequently covers funding for racial equity, and while I won’t dive into more specifics here, a notable perspective was recently shared by Ford, one of the biggest funders in this space. Ford has a long history of efforts to address the racial wealth gap, which was central to the asset-building work that the foundation embarked on in the mid-1990s under the leadership of Melvin Oliver, co-author of a groundbreaking 1995 book on the topic, Black Wealth/White Wealth. After years of funding in this realm, the foundation commissioned an evaluation of its work by the Roosevelt Institute and the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society. A key finding was that, along with helping black individuals to build assets, structural changes that will allow black families to accumulate and pass down wealth between generations are essential and lacking.

The report states that Ford-funded research “illustrated the [ways] historical and present-day exclusions in the labor market, housing, education and so many other domains compound with existing economic rules that disproportionately strip wealth from low-income families and families of color, affecting economic opportunities and outcomes across generations.” Tax reform, curbing corporate power and “getting money out of politics” are among the potential large-frame solutions mentioned. The report concludes that greater progress toward closing the racial wealth gap will require funding for both individual and structural reform.

PRE Executive Director Lori Villarosa tells us it’s important that more funders are “making the linkages between slavery and colonization and ongoing structural racism… But philanthropy must further increase support for remedies that directly tackle systems that were built to preserve white supremacy, perpetuating anti-blackness and other racial biases, while seeming to be race-neutral.” She says, “Solutions should be as explicitly targeted and racialized as the problems,” but that they will “usually also improve conditions for all communities.”

Philanthropy for Truth, Healing and Reconciliation

In addition to the many crucial social, economic and political efforts, funders can support the descendants of enslaved people by talking about slavery and racial injustice within the philanthropic sector and by backing programs that foster community dialogue on these topics. Schlegel tells funders, “Invite others into your archives [and] your endowment to educate you about the sources of your wealth… Challenge your peers to embrace discomfort and step into their own leadership role to move our country forward toward racial equity.” He says funders can wield their power and influence by talking to other people who have wealth or wealth access about slavery’s “living legacy” and about how amends can be made.

“The way to right wrongs is to turn the light of truth upon them,” said black writer, abolitionist and feminist Ida B. Wells. Community racial healing and amends can be pursued through truth-telling and listening, research and documentation, the creation of ceremonies and monuments, and reconciliation and reparation processes. These stages are some of the hallmarks of truth and reconciliation commissions (TRCs), an imperfect and still evolving process made famous by South Africa post-apartheid.

These strategies have received attention from philanthropy on the global, national and local stage. The Open Society Foundations, Ford and others support a transnational organization in New York called the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). Transitional justice describes how countries deal with large-scale atrocities or human rights abuses (like slavery), including through TRCs. ICTJ helps countries pursue accountability and healing, and is funded by foundations, governments, individuals and multilateral organizations. It has supported transitional justice work in South Africa, the former Yugoslavia, Argentina, Nepal, Myanmar and dozens of other countries.

Atlantic Philanthropies runs its Reconciliation and Human Rights program in countries including South Africa and Northern Ireland. Its grantee partners have carried out activism, archiving, communications and memorialization related to national truth and healing programs. In Canada, a group of community foundations called The Circle has committed to carrying forth the principles of the country's TRC work regarding harms against indigenous peoples.

Within the U.S., truth and reconciliation processes have occurred on a smaller, local level, often led by grassroots efforts. A notable example is the 1999 Greensboro, North Carolina, TRC, the first formal process of this kind in the country. It addressed a 1979 incident in which armed Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi Party members attacked protestors at an anti-Klan demonstration, killing five people. The crime was clearly filmed, yet no one was convicted. After community testimony and a final report, follow-up efforts to promote reconciliation and address inequality included an investigation into police discrimination and the creation of a memorial site.

Greensboro’s TRC was supported by the Andrus Family Fund, JEHT Foundation, Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, and others. The commission also received guidance from ICTJ. Multiple other in-progress or completed TRC programs can now be found throughout the U.S., including in Boston, Detroit and Charlottesville. Many relate to racial issues, and are potentially a powerful way for funders to support individual communities, or even regions, in unwinding and addressing slavery’s many ramifications. And as many other countries have shown, national TRC processes are tricky but possible, and sometimes rely on a combination of public and private funding.

The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, a major backer of racial equity programming, created several initiatives that center truth-telling and dialogue. Through its America Healing project, it supported the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, based in Mississippi. The institute convened New Orleans residents of diverse backgrounds to participate in truth circles, in which they shared their experiences with racial issues. These circles were a contributing factor in the city’s choice to remove its Confederate memorials.

Building on this work, Kellogg also created the Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation initiative (TRHT). In 2017, it committed $24 million to 144 TRHT partners in 14 areas of the country to address local racial divides. It collaborates with many regional and community foundations in this work. TRHT backs grassroots organizing and policy work on issues like residential segregation and economic mobility, building on some of Kellogg’s previous substantial investments of this kind. It also funds healing and relationship-building initiatives, continuing the model of bringing community members of various sectors, identities and perspectives into conversation. And THRT seeks to fuel narrative change to better capture the complex and diverse stories and voices of the country’s past, present and future within news, media, schools and other spaces. This focus on narrative is similar to a culture change strategy recently adopted by gender justice funders in California.

In January 2019, TRHT partners celebrated the third National Day of Racial Healing, an event Kellogg conceived. TRHT groups held racial healing circles, community storytelling events, bus tours, concerts and various artistic experiences.

Truth and healing-based philanthropy and nonprofit programming, along with other communication-reliant strategies like restorative justice, stand out because of their focus on taking the time to listen, reflect and share. This is a sort of slow philanthropy, with change occurring in subtle internal differences in one person at a time, which can culminate in the deeper societal shifts sought after by funders. These types of personal, human programs are an important piece of the puzzle; they are valid unto themselves, and can also lay the cultural groundwork for the development of the many pragmatic economic and policy supports racial equity requires.

The Question of Reparations

TRC programs may also involve offering apologies. In the U.S., multiple presidents have acknowledged slavery’s destructive legacy, and some states have crafted their own apologies. While the House and the Senate (in 2008 and 2009, respectively) put forward resolutions apologizing for slavery, no joint bill passed. At times, TRC processes also include financial reparations for those harmed or their descendants. In 1988, the U.S. government formally apologized for the practice of Japanese internment during World War II and gave reparations to living survivors.

The topic of financial reparations for slave descendants is again gaining public and political attention, even surfacing in the 2019 Democratic primary debates. In June, the House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties held a hearing on reparations—the first in more than a decade. In a 2019 Gallup poll, 67 percent of Americans opposed reparations from the government, and 29 percent supported them. About 73 percent of black Americans were in favor, in contrast to 16 percent of non-Hispanic white Americans.

Professor William Darity Jr. of Duke University, co-author of a forthcoming book on reparations, is in favor of it. He told Mother Jones it would take between about $10 and $12 trillion to carry out. He said a government-based program could frame reparations as a national debt and obligation, rather than an issue of any individual or family’s “particular guilt.”

Darity is also a proponent of “baby bonds,” in which each child born would receive a trust fund, the size of which would vary in relation to the family’s wealth. Ford has supported Darity’s work, and its recent evaluation calling for structural reforms upholds baby bonds as one of the “bold solutions” that may be necessary to address the racial wealth gap. A 2019 analysis by Columbia postdoctoral researcher Naomi Zewde finds baby bonds would “considerably narrow wealth inequalities by race.” Ford has funded a trial of a similar type of program, Child Development Accounts, or CDAs, since 2007. The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation is another leader in addressing the racial wealth gap, as we’ve reported, with its longstanding support of Children’s Savings Account, or CSA’s (another name for CDA’s).

While reparations are generally seen as a governmental responsibility, it’s interesting to consider whether U.S.-based foundations, whose assets exceeded $1 trillion for the first time in fiscal year 2017, owe a direct debt to black Americans. Or does all philanthropy targeting black communities already intrinsically represent a form of reparation? Chiara Cordelli, assistant professor in the department of political science at the University of Chicago, wrote that in “non-ideal contexts, philanthropy should foremost be understood as a means of reparative justice,” and that donors “ought to conceive of their giving as a public action, rather than as a private gift, and thus as subject to stringent moral constraints.” But should philanthropy collectively and purposefully pay some form of direct financial reparations to communities of color?

Philanthropy professional and writer Edgar Villanueva has considered a possibility akin to this; he is a proponent of using “money as medicine” to right societal wrongs. In his book, Decolonizing Wealth, he drew on indigenous wisdom and called for U.S. financial and philanthropic institutions to undertake a multistage process of healing and reconciliation with communities of color. He suggested several types of amends that could be made, including the potential creation of a communal tithe and fund by U.S. foundations.

"The institutions of philanthropy as a whole could take 10 percent of their assets—10 percent tithed from each foundation in existence—and establish a trust fund to which Native Americans and African-Americans could apply for grants for various asset-building projects, such as home ownership, further education or startup funds for businesses… No strings attached,” he wrote.

Hill Edwards isn’t sure how this idea would work out practically, but she thinks “these types of proposals are important as we discuss the ways that we can bring about change for people who have been affected by the legacy of slavery.” She does not support direct financial reparations from the government.

Buckner Inniss says Villanueva’s’ ideas “resonate” with her. “While Native and African-American communities suffer numerous ills, many of them come back to the persistent, large [racial] wealth gap.” She says there are clearly systemic and institutional reasons for the gap, and that private philanthropy acknowledges this “chasm,” but doesn’t do enough to address it. She suggests funders create “a real estate trust that would provide afro-descendants funding to buy and maintain primary homes.”

Buckner Inniss also discusses reparations in relation to the recent Mellon grant to William and Mary. She says most schools exploring these histories “are those venerable enough to have existed during the period of Antebellum enslavement in the U.S... there is almost an extent to which they burnish their own reputations in undertaking [these] examinations.” And among the calls for research, recollection and reconciliation, she says, “there is a crucial ‘R’-word missing: reparations.” When they are offered, she says they are limited, as in Georgetown’s offer of preferential admission for descendants of enslaved people. She says U.S. philanthropies can “change the conversation to one that focuses on materially aiding descendants of the enslaved.”

I asked Villanueva for his current thoughts on philanthropy that addresses slavery's legacy. He says, “We’re in a special moment of truth telling and coming to terms with our past as a nation, as a sector. What has happened cannot be undone, but we need to enter an era of storytelling, of deep listening, of understanding the truth and shifting the narratives that are making it difficult for us to reconcile our commitment to equality and justice.”

Four centuries after American slavery began and 154 years after it ended, related funding is still evolving and necessary. It comes in many shapes and sizes, from nationwide economic reform to neighborly conversation. A disability-rights motto that has been adopted by participatory grantmakers is applicable to this vein of philanthropy: “Nothing about us without us.” Black-led efforts that draw on the black community’s assets, aspirations and power have the strongest roots and the most promise to build a more equitable country.