“Where are the Women?” A Bequest Cements a Patron’s Legacy of Promoting Female Artists

/Fabio Balbi/shutterstock

In an essay in “The Art Market 2019,” sociologist Taylor Whitten Brown underscored the extent of gender disparity across the art world. Since 1999, female artists’ work sold at a lower median price than that of their male counterparts. Works by female artists comprise a small share of major permanent collections in the U.S. and Europe. And only two works by women have ever broken into the top 100 auction sales for paintings.

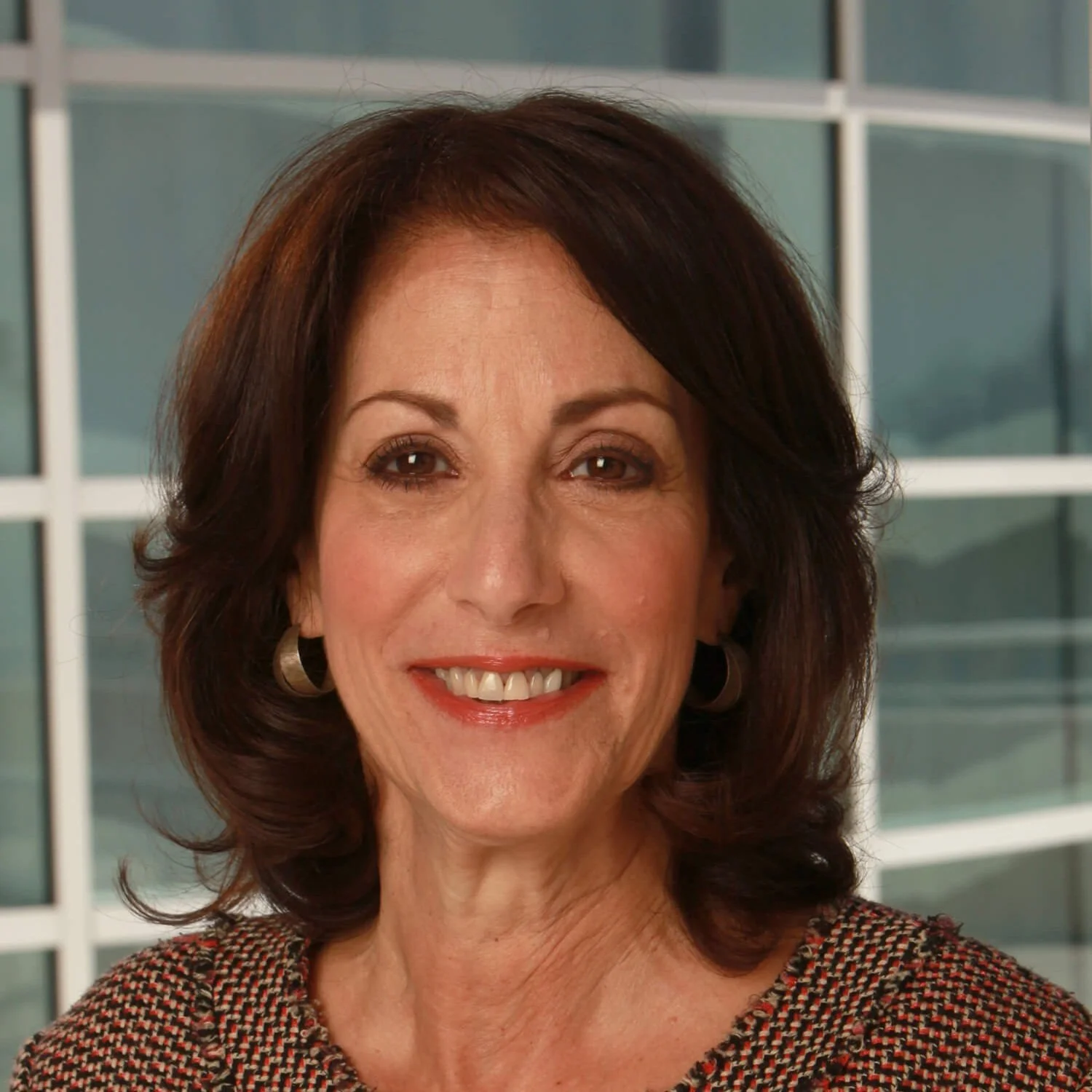

Buoyed by the equity push sweeping modern philanthropy, some arts funders have been seeking to remedy these entrenched disparities. The most recent example of this dynamic comes from Indiana University, where the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art announced an estate gift with an estimated value of $4 million from the late philanthropist, author and journalist Jane Fortune, who passed away in 2018. Fortune’s gift includes a collection of 61 works of fine art, as well as funds to establish the Dr. Jane Fortune Endowment for Women Artists and the Dr. Jane Fortune Fund for Virtual Advancement of Women Artists.

Born and raised in Indianapolis, Fortune spent her junior year of college in Florence. In 2005, she was touring the city’s collection of Italian Renaissance work and noticed the conspicuous absence of female painters. “Where are the women?” Fortune wondered.

Four years later, at the age of 63, Fortune started the Florence-based nonprofit Advancing Women Artists (AWA) to find and restore work created by women between the 16th and 20th centuries, earning her the nickname “Indiana Jane” by the Florentine press. “The idea to restore art by women started as a way for me to give something back to the city I most love,” she said in 2015.

Fortune’s mother was a journalist. Her father came from a long line of civic leaders and philanthropists. As philanthropists, her parents “were very powerful role models,” Jane said in a 2010 interview. '“Giving back was in their DNA. They believed that since they were so fortunate, it was their responsibility. My dad never passed a beggar on the street without acknowledging him or her and giving a dollar or two. We, as their children, are also very fortunate, and feel it is our responsibility to continue Mom and Dad’s legacy, and to make a difference, too.”

Fortune served on the boards of directors for the Indianapolis Museum of Art, the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and the National Advisory Board of the Eskenazi Museum of Art. She was also a founding member of IU’s Philanthropy Leadership Council and co-founded the Indianapolis City Ballet in 2008. In 2010, Indiana University recognized her with its highest academic achievement, an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. Fortune was also active in Philadelphia, New York and Washington, D.C., with a particular focus on increasing accessibility to the arts for people with disabilities.

Explaining the Disparity

“It is not hard to grasp the origins” of gender inequality in the art world, “given that women were largely barred from artistic professions and training until the 1870s,” wrote Brown. “Untangling the reasons that this inequality persists today is more difficult.” These reasons include:

Differences in gallery representation; the cultural biases of art interpretation; the cliché of the art world “bad boy”; the sexism of aging; the imbalanced weight of parenthood; the proportion of curators, collectors and gallery representatives who are female; and the lack of assertiveness among female artists have all been proposed as hypothetical causes.

A review of recent gifts finds funders addressing some of these issues. In an effort to tackle ageism, Anonymous Was a Woman provides annual unrestricted grants of $25,000 to 10 female artists over age 40. Earlier this year, it awarded a grant to 80-year old painter Painter Dotty Attie. The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation remain committed to boosting diversity in museum management and curatorial ranks. And the Swartz Foundation, the Bernstein Family Foundation and the Reva and David Logan Foundation are helping female artists navigate the intersection between the arts and social activism.

Funders are also working to ensure that female artists enjoy greater representation in museums and galleries. Proponents of this approach include Barbara Lee, a prominent Massachusetts philanthropist and art collector; arts philanthropist Madeleine Rast, who passed away in 2017; collectors like Francie Bishop Good and David Horvitz; Agnes Gund, who, while in the news thanks to her Art for Justice program, has also spent her life supporting female artists; and the sunsetting Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, which made a $5 million gift to enable the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art to create an endowment to digitize material by artists from “historically underrepresented groups,” including women.

The Berkeley-based WomenArts provides an extensive list of additional active funders in this space.

Building the World’s Largest Database on Female Artists

Back in 2016, the IU Art Museum was renamed the Sidney and Lois Eskenazi Museum of Art in acknowledgement of a $15 million gift from Indianapolis-based philanthropists Sidney and Lois Eskenazi. It was the largest cash gift in the museum’s history, and a lead gift toward the building’s renovation.

Upon announcing the Fortune bequest, the museum announced it was entering a “new phase with a renovated building that includes new areas for learning and teaching. The renovation enhanced the museum's mission as a preeminent teaching museum through the creation of four new centers that will provide more space for educational resources for university students, faculty and preschool through high school students. Fortune's generous endowments will further enhance the museum’s ability to broaden its outreach.”

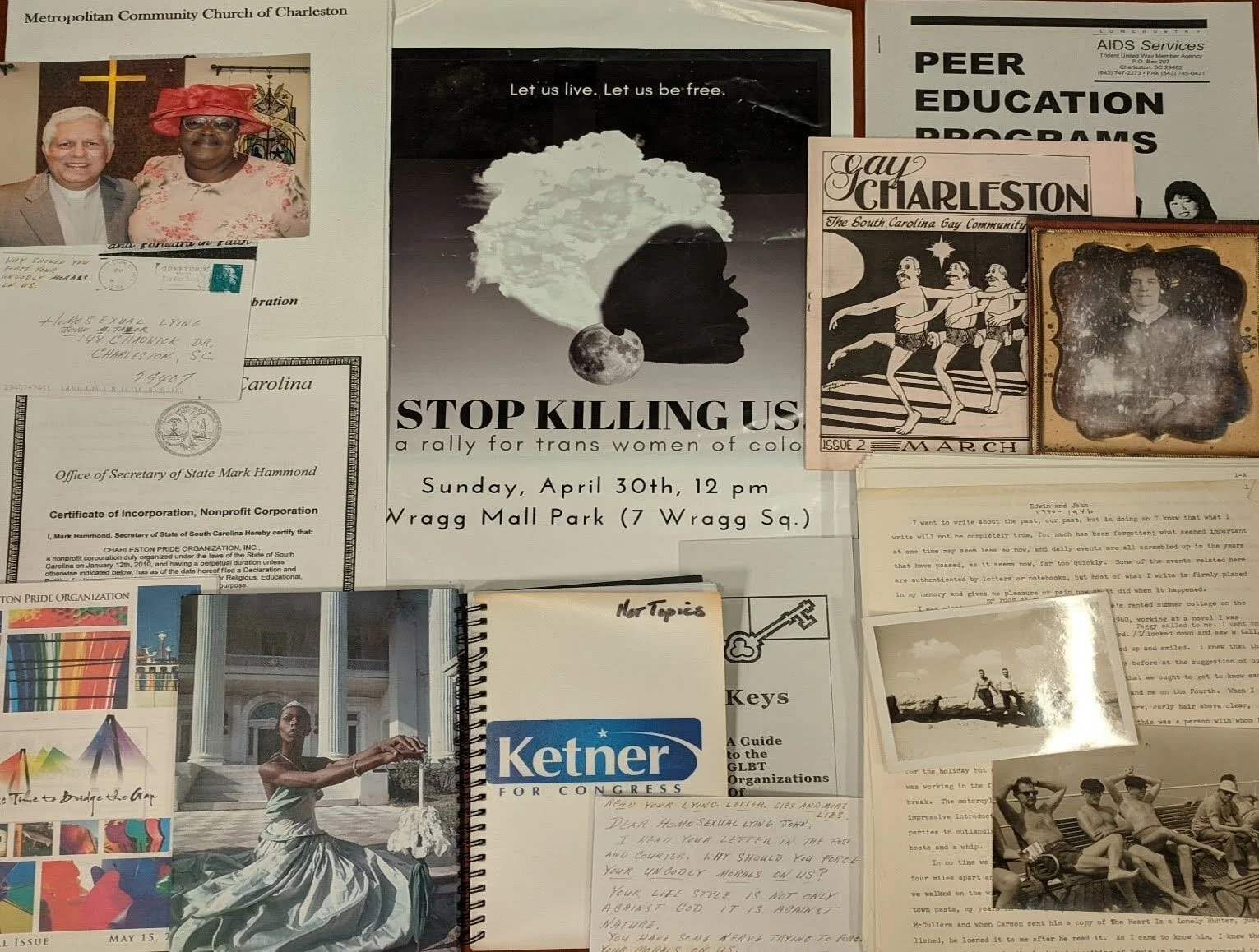

One such educational resource is A Space of Their Own, which brings together research by AWA, the Eskenazi Museum of Art and IU to build the world’s largest database on international female artists from the 1500s to the 1800s. Fortune considered the project an outgrowth of her work researching and exhibiting underappreciated Italian women artists.

“The ultimate goal of this project is to raise awareness among museum executives first, and then for the general public. Historic women artists have contributed to their visual culture against incredible odds,” said AWA Director Linda Falcone. “Women’s history is not a given. The fact that many of these women were famous in their own day and now are almost forgotten tells us a lot.”

Fortune’s bequest is part of IU’s $3 billion fundraising campaign, For All: The Indiana University Bicentennial Campaign. It blew past its original goal of $2.5 billion in October of 2017, and immediately upped its target by a half-billion dollars. This has become an increasingly familiar phenomenon for fundraisers at public universities thanks to alumni looking to elevate their alma mater’s national stature, funders stepping up in the face of shrinking state appropriations, increasingly sophisticated and “always-on” fundraising operations, and the longest bull market in history.

IU’s success comes as other public universities, including the University of Michigan, the University of Alabama, the University of Arizona, the University of Houston, and the University of Florida have either met or announced highly ambitious fundraising campaigns.